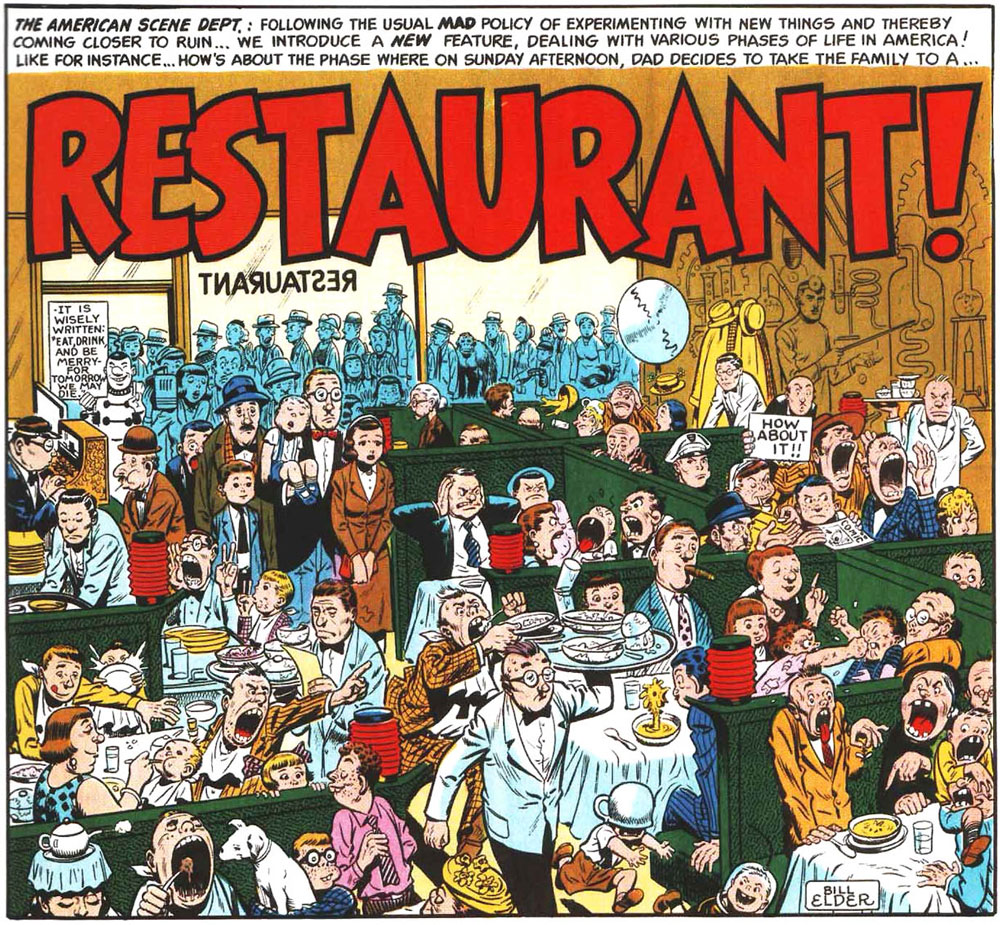

'Restaurant!' (Mad #16, October 1954).

The American humorous cartoonist Will Elder was one of the pioneering artists in Mad Magazine. A skilled parodist, his wacky, detailed panels, stuffed with countless background gags, helped shape Mad's trademark graphic style and received the nickname "chicken fat". Elder is often named in one breath with Harvey Kurtzman, his editor and scriptwriter, with whom he frequently collaborated. In addition, Elder was also the first artist to draw Mad's mascot Alfred E. Neuman, though the character was later streamlined by Norman Mingo. Later on, Kurtzman and Elder also created comics for Kurtzman's other satirical magazines Trump, Humbug and Help! In the latter publication, their most significant series was 'Goodman Beaver' (1961-1965), a good-natured but confused simpleton, lost in modern society. The witty satirical concept was retooled when Elder and Kurtzman joined Hugh Hefner's Playboy magazine and turned Goodman into a big-bosomed sex bomb, 'Little Annie Fanny' (1962-1988). This feature showed off Elder's talent for erotic art, rendered in lavish, oil-painted panels. Will Elder remains one of the most influential graphic humorists of all time, whose comics still have a large cult following. A notorious prankster, Elder was also the only Mad cartoonist to be as nutty in his private life as in his comics, as Mad publisher William M. Gaines once attested.

Early life and career

Wolf William Eisenberg was born in 1921 in the Bronx, New York City, as the child of poor Polish-Jewish immigrants who had initially settled in England, but later moved to the USA. His father was a suit presser in a clothing factory. To avoid landlords, the Eisenberg family moved around a lot, living with relatives during short periods of time to minimize costs. The boy sought escapism by reading, drawing, clay-sculpting and playing pranks. In school, Elder was the class clown. One time, he pretended to be absent, but in reality he was hiding inside the cloakroom, having whitened his face with chalk and hanging by his coat, pretending to have hung himself. When the teacher discovered him, he nearly fainted.

Elder built up a lifelong reputation as a prankster. Once he painted a closet door on a wall of his house, attaching a loose doorknob to it. When his aunt tried to open this non-existent door, she pulled so hard on the knob that it sprang loose, landing her on the floor. Elder's pranks could be very elaborate black comedy. One time, he took a bunch of children's clothing, put meat in it and left it near the railroad tracks, pretending a certain "Mikey" had been squashed by a train. Naturally, he sent panic waves among every mother who had a son with that name. The police eventually arrived to take the blood-soaked clothes away. In a variation on this gruesome prank, Elder once sprayed himself with ketchup, pretending to be badly hurt. His mother called an ambulance and Elder didn't dare to admit it was all a sick joke. Only when the doctor examined him, he was sent back home. Even in adulthood, he kept fooling people and entertaining his friends, relatives and colleagues. He once went to a public meeting where Miss America Bess Myerson would be present and told his friends that he and she used to be classmates. When they didn't believe him, he took a bet with them. Much to their surprise, she indeed instantly hugged him.

'Last Laugh' (Tales from the Crypt #38, October-November 1953).

A big comedy fan, Elder's favorite comedians were Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, Laurel & Hardy and The Marx Brothers, and he also enjoyed audio plays on the radio. Among his favorite painters were Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hieronymus Bosch, Honoré Daumier, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, while he admired cartoonists Leslie Illingworth, Walt Disney, Rudolph Dirks (especially since he recognized himself in The Katzenjammer Kids' pranks), Milton Caniff, Roy Crane, Milt Gross, Bill Holman and Walt Kelly. He enjoyed Bruegel's crowd drawings, where every person is individualized and has his own little droll scene. In 1933, he took the word "Elder" from Bruegel's nickname and started signing all his work with this pseudonym, making it his official last name in 1949. Early in life, he went by the name "Bill Elder", but he later stuck on "Will Elder".

During stickball games, when he was not on the field, Elder would caricature his fellow players to pass the time. At his house, he had a self-made painting of a deer standing in a landscape. Every time the seasons changed, he altered the imagery, for instance, adding snow, blossoming spring flowers or falling autumn leaves. His colleagues remembered that Elder kept this tradition up for years. As a teenager, he applied for a job at the Disney Studios, but was rejected. At age 14, Elder went to the New York High School of Music and Art, where he met many of his future colleagues at Mad, including Al Feldstein, Al Jaffee, Harvey Kurtzman, John Severin and Marie Severin. At the time, though, Elder and Kurtzman never spoke, but the latter was aware of Elder through his colorful pranks.

After graduation in 1940, Elder drew cartoons for The Decal Company in Manhattan, specialized in stickers and insignia for cars and university colleges. However, he stayed there only for three months, because he wanted to find something better.

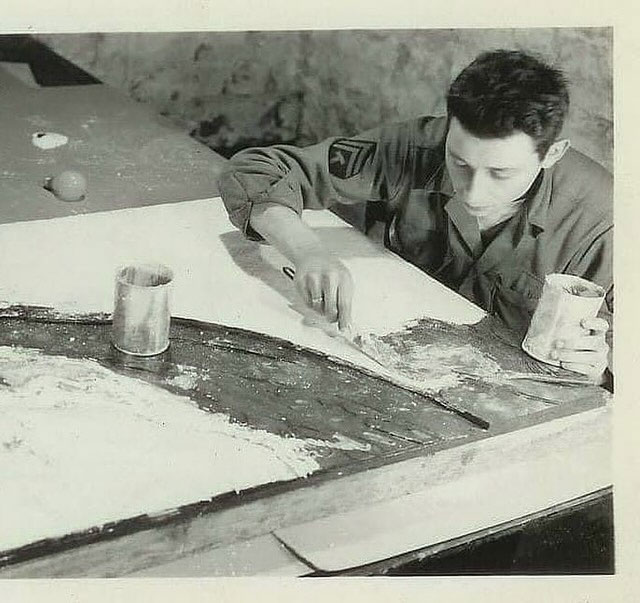

Will Elder during World War II.

Military service

In 1941, the USA entered World War II and Elder went to serve his country the next year. Part of the 668th Engineer Company of the First Army, his main duty was cartography and photo-mapping. He was part of a group of six mapmakers who helped design the topographical map in preparation of the Allied Invasion. The project was so secret that only they and the generals were aware of the exact location. To fool the Nazis, the Allied Forces implied through various intentionally leaked "secret" plans that they would invade the South coast of France. As the Nazis intensified the defense in the South, they were shocked when D-Day eventually took place up North, in Normandy. Even though he was mostly involved in topography and engineering, Elder saw a sure amount of action. On D-Day, he was part of the forces that stormed the Omaha Beach and then fought further into Europe. His regiment participated in the liberation of Cherbourg, Paris and Pilsen (Czechoslovakia), and also took part in the Battle of the Bulge (Belgium) and the storming of Cologne (Germany). In Europe, Elder was involved in the liberation of two concentration camps, one of which was a death camp. There, he saw enough horrors to avoid talking about the subject in public. Elder was also assigned to draw propaganda and educational posters for the U.S. Army.

'Rufus De Bree' from Toytown Comics #6 (March 1947).

Charles William Harvey Studio

Back in civilian life, Elder first worked on some advertising assignments for a New York publishing house, until he met his old friend Charles Stern on the streets, who was accompanied by the cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman. In 1946, the three men teamed up and established the Charles William Harvey Studio, located at 1151 Broadway in New York City. The studio housed many future talents, mostly people who later became associated with Mad, such as John Severin and David Berg, but also foreigners like future 'Astérix' creator René Goscinny. Back then, Elder was predominantly an inker for Severin. At the time, Elder was a very slow penciler but a skilled inker, whereas Severin was fast with a pencil but less comfortable inking. Between 1948 and 1951, for Prize Comics Western (Feature Publications), they drew western features like 'Lazo Kid', 'Black Bull' and 'American Eagle', as well as romance stories for the Better Publications/Pines titles Real Life Comics, Thrilling Romances and Western Hearts.

Elder's first solo comic feature was 'Rufus De Bree' (1946), printed in Toytown Comics. The plot revolves around Rufus, an old street sweeper who is frustrated with his job, but finds escapism in tales of chivalry. One day, an ice cream truck runs him over and Rufus lands in a coma. He then starts dreaming that he's a knight, with the truck driver, Mac, as his sidekick. Like an alternative version of Don Quixote and Sancho Pancha, they have adventures in a medieval fantasy setting. Four stories in total were made, published in issues #4 (October 1946) and #7 (May 1947). As Toytown Comics didn't sell well, the comic book series was abruptly terminated, leaving Rufus forever in his fantasy-induced coma.

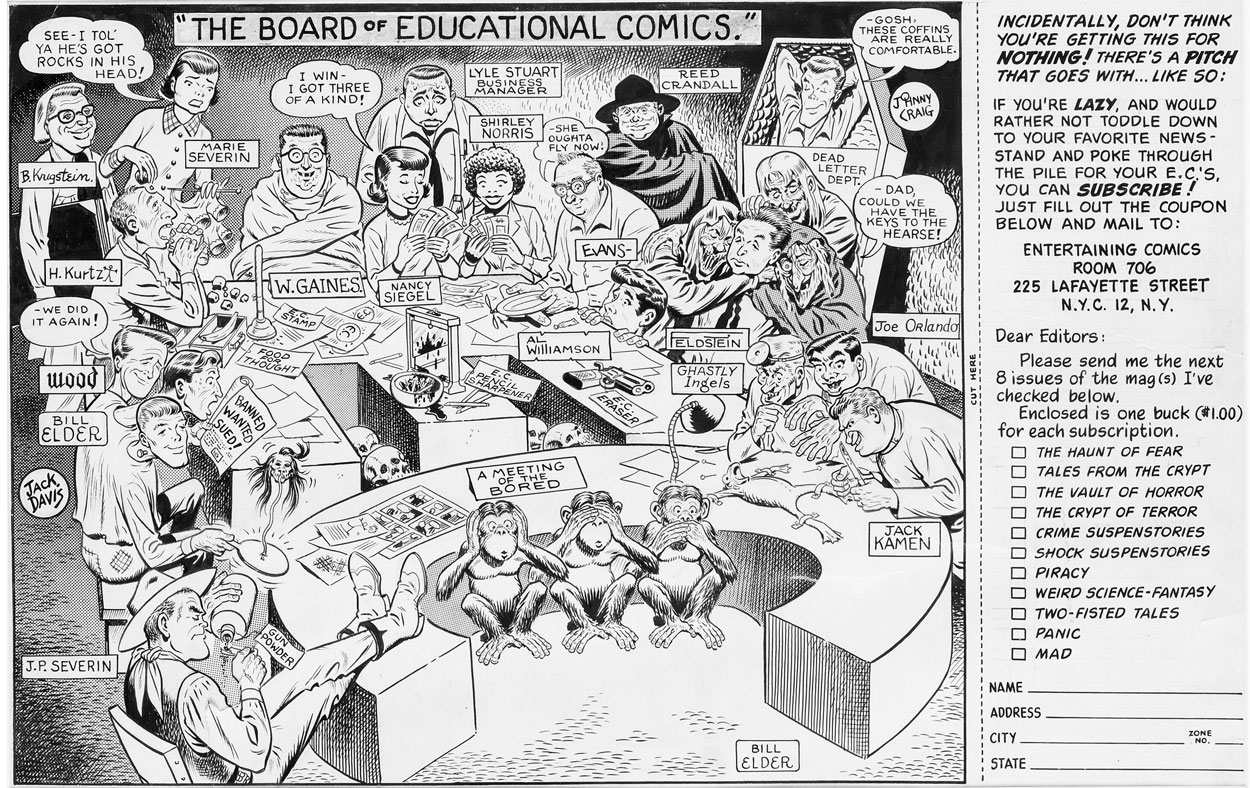

Promotional drawing for EC Comics.

EC Comics

In 1950, Harvey Kurtzman and most of his Charles William Harvey Studio staff joined EC Comics, the publishing company led by William M. Gaines and his editor Al Feldstein. At first, Elder remained an inker for John Severin, contributing to EC 's horror and military comics. He sometimes collaborated with Jack Kamen too. At a certain point, Elder also penciled some stories himself, like 'Inside Story!' (Weird Science, issue #14, July-August 1952) and 'Right on the Button' (Weird Science, issue #18, May-June 1953). For Weird Fantasy issue #17 (January-February 1953), he drew 'Ahead Of The Game!' and in the Crime SuspenStories series '…Two For The Show' (issue #17, June-July 1953) and 'Juice For The Record!' (issue #18, August-September 1953).

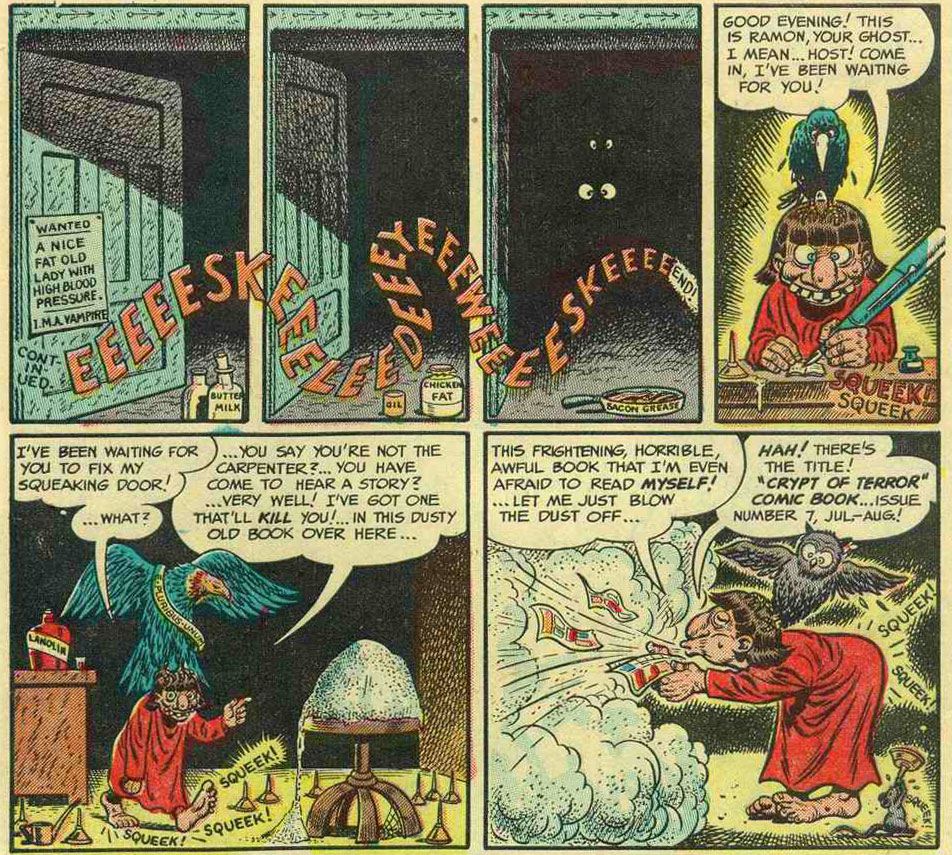

To the horror comic Tales From the Crypt, Elder contributed 'Strop! You're Killing Me!' (issue #37, August-September 1953) and 'Last Laugh' (issue #38, October-November 1953). 'Last Laugh' is notable for its autobiographical tone: the plot revolves around a morbid prankster who, just like Elder, once put some meat in old clothes and dropped them at the railroad track to have a good laugh. Yet, true to the nature of EC's horror comics, this story has a more macabre plot twist. Looking back on his drama comics for EC in a 1983 interview, Elder recalled they "really were not my cup of tea". However, he did draw a beautiful subscription ad for EC Comics, depicting all their most prominent editors, writers and artists in goofy individual moments.

'Mole!' (Mad #2, December 1952).

Mad

In 1952, Kurtzman received his own humor comic book at EC Comics, titled Mad. After 23 comic book issues, the title was turned into a satirical magazine, spoofing famous comics, films, novels, advertisements and later also TV shows. Initially Kurtzman scripted all the stories, which were then drawn by EC regulars Jack Davis, Russ Heath, Bernard Krigstein, John Severin, Wallace Wood, Basil Wolverton and Bill Elder. Kurtzman especially wanted Elder to join in, since he was such a notorious jokester. In his opinion, Elder wasted too much thinking about how to pull off certain pranks, while in a comic he wouldn't have to bother about the logic and mechanics behind it. Although Elder usually worked together with Kurtzman, some illustrated articles by him were written by Bernard Shir-Cliff, comedian Ernie Kovacs, Arnold Hayne and James Blish.

'Sherlock Holmes' parody from Mad #6, October 1954).

Mad: film, TV, radio and literature parodies

Elder debuted in Mad's very first issue (October 1952), with the gangster spoof 'Ganefs!'. In the second issue (December 1952), he drew the classic comic 'Mole!', about a criminal who manages to escape from maximum security prisons by digging himself out. No matter how many things his guards confiscate, he always finds something he can use as a shovel. The story became so beloved that it was reprinted in Mad's "special art" issue (#22, April 1955). Once Mad started to focus on specific parodies, it gained a growing following and rose as one of the best-selling humor publications in the USA. Oddly enough, it took a while before Elder started spoofing famous comic series, like his colleagues did. Originally, Harvey Kurtzman assigned him more to lampoon world literature, radio shows and films. Among them 'The Shadow' (issue #4, April 1953), 'King Kong' (issue #6, August 1953), 'Frankenstein' (issue #8, December 1953), 'The Raven' (issue #9, March 1954), 'Robinson Crusoe' (issue #13, July 1954) and 'The Seven Year Itch' (issue #26, November 1955). Elder's first spoof of a TV show appeared in issue #18 (December 1954), tackling the children's program 'Howdy-Doody'. He later also spoofed 'The Ed Sullivan Show' (issue #27, April 1956) and the medical TV drama 'Medic' (issue #28, July 1956). Elder and Kurtzman even spoofed two franchises twice, namely 'Dragnet' (issue #3, January 1953 and issue #11, May 1954) and 'Sherlock Holmes' (issue #7, October 1953, and issue #16, October 1954).

'Wonder Woman' parody in Mad #10 (April 1954).

Mad: comics parodies

Harvey Kurtzman discovered that Elder was a good stylistic parodist. He could recreate the look of well-known comic series so precisely that he was soon asked to make spoofs in this field instead, namely DC Comics' 'Wonder Woman' (issue #10, April 1954), Bob Montana's 'Archie' (issue #12, June 1954), Lee Falk & Phil Davis' 'Mandrake the Magician' (issue #14, August 1954), Frank King's 'Gasoline Alley' (issue #15, September 1954), George McManus' 'Bringing Up Father' (issue #17, November 1954, with part of the story illustrated by Bernard Krigstein), Disney comics (issue #19, January 1955), Rudolph Dirks' Katzenjammer Kids' (issue #20, February 1955) and E.C. Segar's 'Popeye' ((issue #21, March 1955). Even EC Comics' own horror comics were lampooned in 'Outer Sanctum!' (issue #5, June 1953).

Mad: advertising spoofs

Elder was also commissioned to parody well-known advertising illustrations. Al Jaffee once paid him a huge compliment by claiming he would have made "a good forger". Indeed, he took great effort in imitating original comic artwork as authentic as possible, to "fool people to think that this was the real item, and then suddenly make them realize at the last moment that it wasn't." Still, even Elder couldn't resist confessing it: in the previously mentioned Walt Disney spoof 'Mickey Rodent', one of the background signs reads: "Copied, right!".

When Elder drew a cover for Mad in the style of a newspaper advertising page (issue #21, March 1955), he included a tiny face people nowadays recognize as Mad's mascot Alfred E. Neuman. Back then, the character had no name, but he kept appearing in the following issues with the slogan "What, Me Worry?". It wasn't until issue #29 (September 1956) that the gap-toothed boy was named Alfred E. Neuman. Norman Mingo streamlined Alfred more into a full-blown personality, prominently appearing on the cover of issue #30 (December 1956).

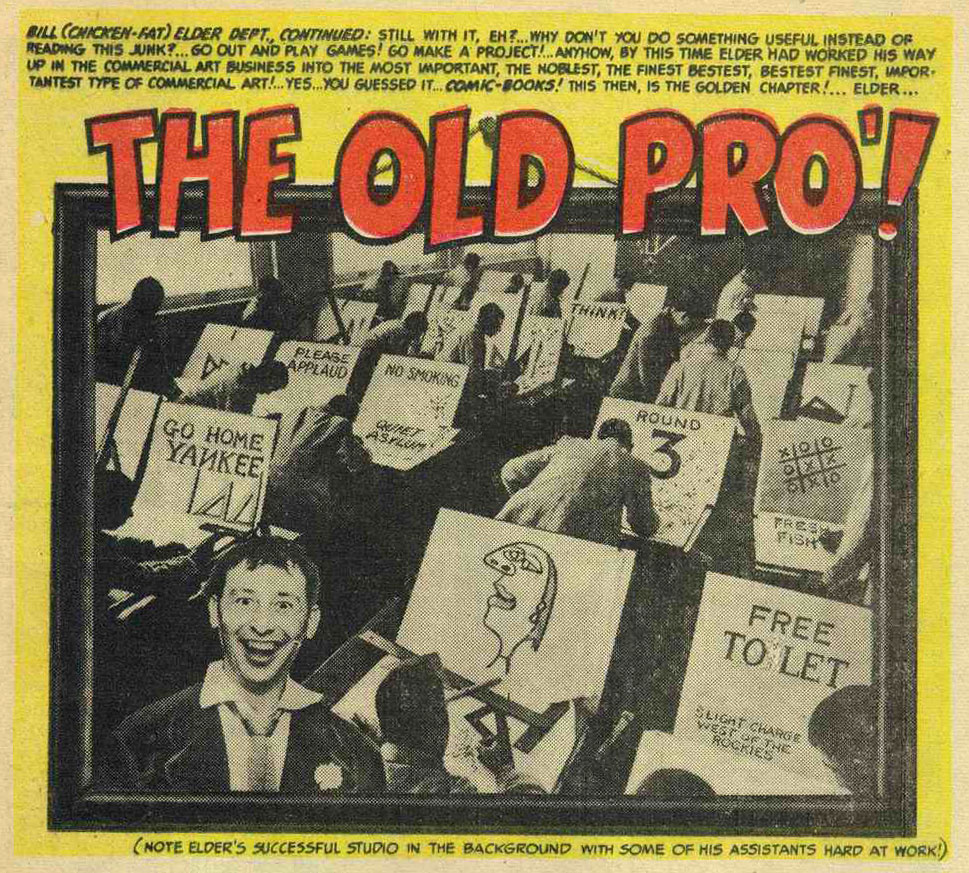

'The Old Pro'!', from the Elder-centered Mad #22 (April 1955).

Mad: other comics

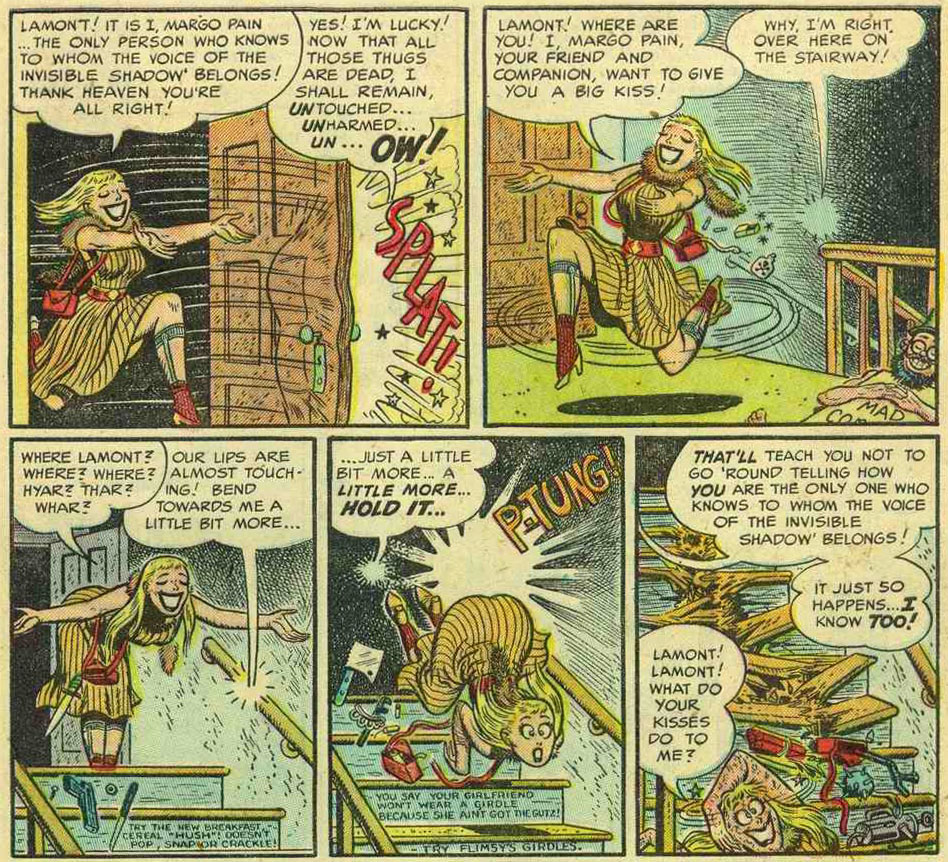

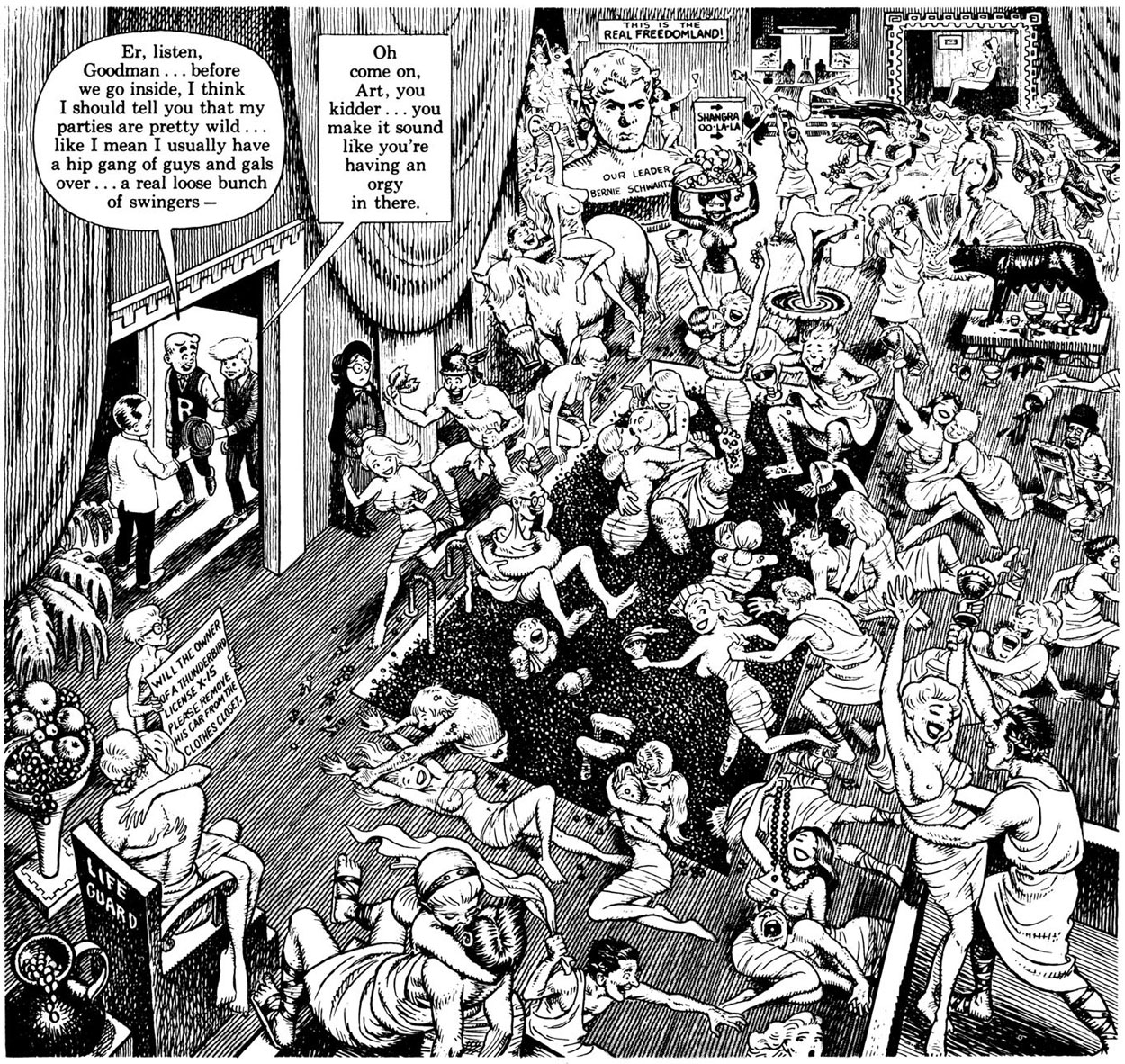

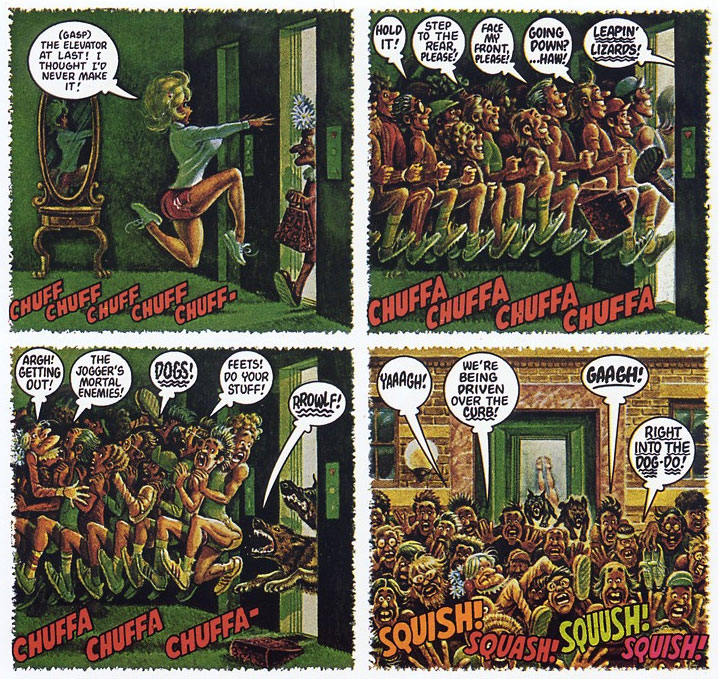

A more timeless classic by Kurtzman and Elder, satirizing restaurants, is 'Restaurant!' (Mad issue #16, October 1954). Elder's notability among Mad readers rose when the 22th issue (April 1955) was entirely devoted to him. Readers were treated to a mock biography of the artist's life. Starting off with his supposed childhood, it continues to his professionalism as a veteran and eventual senility (a page where none of the sentences make sense). Interviewed by Gary Groth for The Comics Journal (issue #254, July 2003), Elder revealed that the 22th issue came about when there wasn't enough material ready and the editors were facing a deadline. As a result, he was asked to draw the entire issue on his own. Although Elder did his best, in the end some pages still had to be stretched out with photo collages instead of drawings, throwing in a reprint of 'Mole' for good measure.

'The Shadow' (Mad #4, April 1953).

Style: chicken fat

Among the pioneering artists during the first four years of Mad, Elder quickly became the readers' favorite. His drawings have schwung, energy and simultaneous elegance. Characters' actions and emotions are exaggerated beyond the definition of "silliness": they, for instance, tend to skip instead of walk. Seemingly afraid of "horror vacui" ("fear of empty spaces"), Elder filled up his drawings to the brim. Any gag that came in his mind was thrown in. Funny signs pop up out of nowhere. Characters drastically change appearance in between panels. Bizarre people and animals walk in the frame, as if they stumbled onto the wrong set. Famous literary, film, radio, advertising and comic characters make random cameos. Silly objects are scattered on floors, shelves, walls, doors or fall out of wardrobes. For the sake of a hilarious visual gag or corny pun, Elder abandoned any sort of logic or continuity.

In 'Restaurant' (Mad issue #16, October 1954), for instance, a hungry family wants to order dinner, with their son gradually chewing up the table cloth in starving despair. One of the background signs reads "Chinese restaurant: Few men chew" (a pun on the literary character Fu Manchu). Other guests in the place are Sidney Smith and Stanley J. Link's Ching Chow, the 'Bufferin' Man' advertising character, the "His Master's Voice" dog and Terry Lee & Pat Ryan from Milton Caniff's 'Terry and the Pirates'. In Mad's spoof of the crime TV series 'Dragnet' ('Dragged Net', issue #11, May 1954), the hard-boiled crime fighters are followed by the orchestra blaring out their theme music. Among the menagerie of musicians there are a hillbilly jug player, an African drummer, a Japanese biwa lutist and even an entire fairground carousel, but also Sherlock Holmes playing the fiddle, Harpo Marx strumming his harp and the three musicians portrayed in Archibald MacNeal Willard's painting 'The Spirit of '76' (1875). In Harvey Kurtzman and Elder's earlier spoof of 'Dragnet' (issue #3, January 1953), the detective duo climbs a mountain, where one of the snowed tops is the logo of film studio Paramount. In the 'Outer Sanctum' story (Mad issue #5, June 1953), the creepy cryptkeeper has a crow on his forehead which changes into a different bird in each panel: the American Eagle, an owl, a toucan and a chicken.

'King Kong' spoof from Mad #6 (August 1953).

Everything is so overloaded with fun and wackiness that first-time readers don't know where to look first. One can always discover something new. Kurtzman referred to Elder's background gags as "eye-pops", while the artist himself named them "chicken fat", because, just like the real-life food, it adds extra flavor, "while too much of it might kill you." The term "chicken fat" first appeared in an Elder comic in the 'Outer Sanctum!' story, when a squeaky door opens. Elder's "chicken fat" approach was imitated by other Mad cartoonists, most notably Wallace Wood, John Severin and Jack Davis. As it became one of Mad's trademarks, later cartoonists like Mort Drucker, Al Jaffee, Angelo Torres, Tom Bunk, Sam Viviano and Tom Richmond also used it.

'Outer Sanctum' (Mad #5, June 1953). Note the mention of "chicken fat" in the second panel.

As chief editor, Kurtzman told his artists to respect his lay-outs and carefully rendered narration and dialogue. In terms of background gags, they received creative freedom. Yet, sometimes they went too far, forcing him to whistle them back. Elder was the only artist who never received such notifications. He suspected that Kurtzman gave him a free pass, because his gags were just too funny to leave out. Still, while Elder's "chicken fat" often seems completely improvised, he did prepare every panel meticulously. He always started out with structuring the lay-out and the character poses, since they had to drive the plot forward. Only after these key elements were all in place, he started including funny background details. If there was too much graphic overload, the background action was put in a spot color (typically blue or purple), while the foreground action received more color variety. Particularly his spoofs required elaborate research, time and effort, since he wanted to accurately mimic the look of the original.

Just like Kurtzman, Will Elder also enjoyed sprinkling Yiddish slang and Jewish-themed jokes in his work. The title of the very first Elder comic in Mad, 'Ganefs!' is a Yiddish word meaning "thieves". In his 'Frankenstein' parody, a gangster reads a newspaper in Hebrew handwriting. In Mad's first 'Dragnet' parody, some meat hangs in a cave, with the word "kosher" written on the bag.

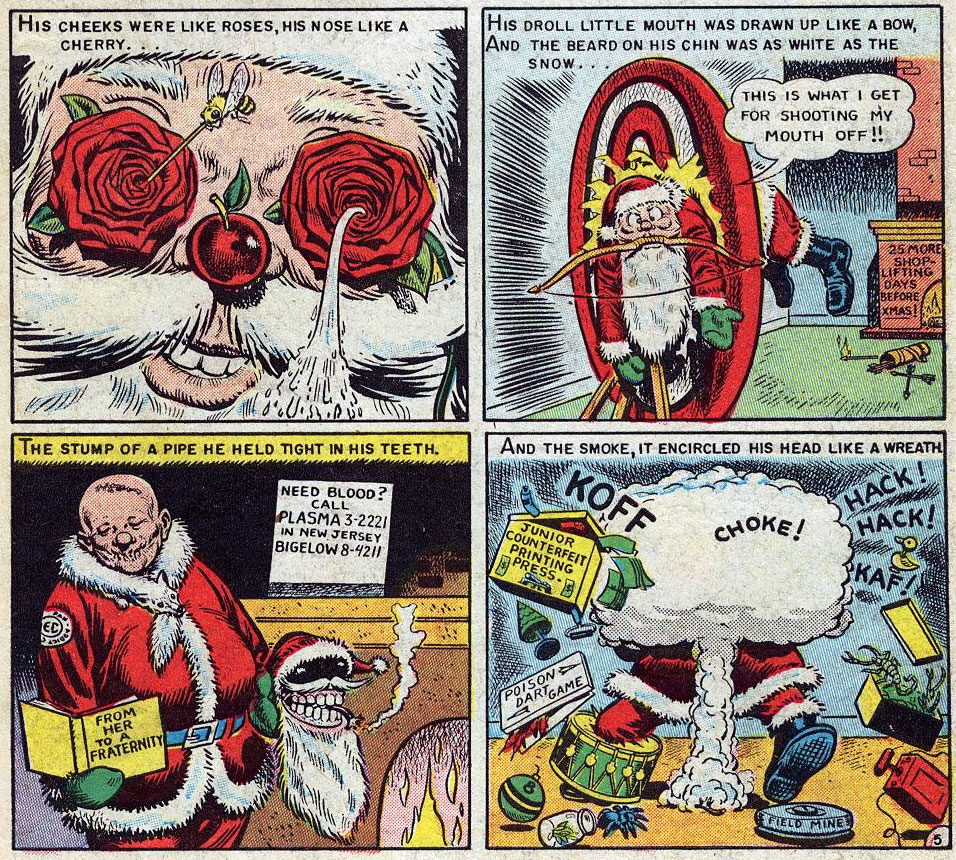

'Twas the Night Before Christmas' (Panic #1, February 1954).

Panic

Between February 1954 and 1956, Elder's work could also be found in EC Comics' other satirical magazine, Panic, edited by Al Feldstein. Since Feldstein had no time to write scripts, he passed this task on to Jack Mendelsohn and Nick Meglin. Yet both men agreed that they didn't need to guide Elder, since he was already "funny enough". It gave Elder more leeway to almost completely write his own stories. Among his memorable spoofs were literary classics like Clement Clarke Moore's 'Twas the Night Before Christmas (issue #1, February 1954), the folk tale 'The Lady of the Tiger?' (issue #2, April 1954) and 'Charlie Chan' (issue #12, December 1955). But most of his output for Panic were spoofs of other comics, namely Al Capp's 'Li'l Abner '(issue #3, June-July 1954), Walter Berndt's 'Smitty' (issue #4, August-September 1954), Chester Gould's 'Dick Tracy' (issue #5, October-November 1954), Lee Falk & Ray Moore's 'The Phantom' (issue #6, December 1954), Ham Fisher's 'Joe Palooka' (issue #7, February-March 1955), V.T. Hamlin's 'Alley Oop' (issue #8, April-May 1955), Nicholas P. Dallis' & Marvin Bradley's 'Rex Morgan M.D.', (issue #9, June-July 1955), Roy Crane's 'Wash Tubbs' (issue #10, August-September 1955), Allen Saunders and Ken Ernst's 'Mary Worth' (issue #11, October-November 1955) and Stan Drake's 'The Heart of Juliet Jones' (issue #12, December 1955).

Spoof of Stan Drake's 'The Heart of Juliet Jones' and Alex Raymond's 'Rip Kirby' (Panic #12, December 1955).

Elder's version of 'Twas the Night Before Christmas' was banned in the state of Massachusetts, because it mocked Santa Claus, as Elder had drawn a "Just divorced" sign on the back of the sleigh. As Santa was considered a saint, he couldn't have been married, the state attorney attested. Later, when EC Comics editors William M. Gaines and Al Feldstein had to testify in front of a Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, Gaines was specifically asked about this particular spoof and defended it because "Santa Claus is not a religious figure, but a phony character invented by Thomas Nast". It didn't help: EC Comics still had to have all their publications checked by the Comics Code authority for potential censorship and even devoted Mad fans felt Panic was nothing more than just another imitation of their favorite magazine. After 12 issues, Panic folded.

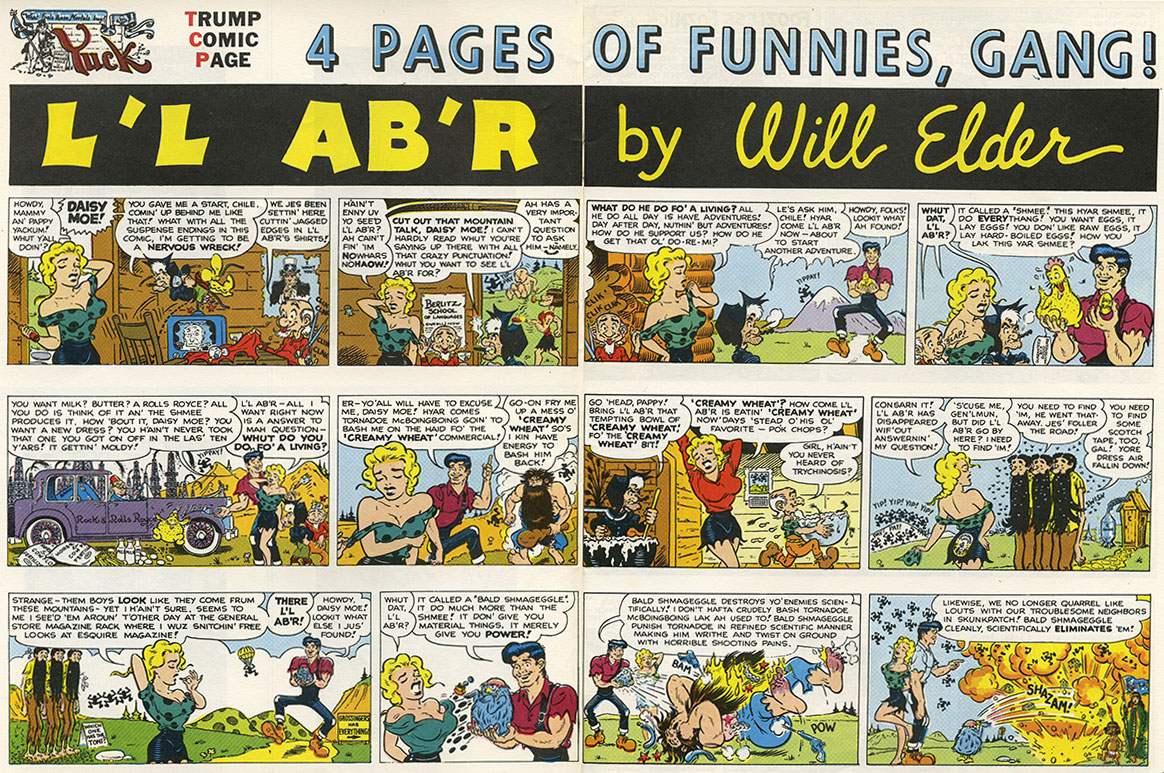

'L'Il Ab'r' (Trump #1, January 1957), parody of Al Capp's 'Li'l Abner'.

Trump

In 1956, the witch hunt against comics, ignited by psychologist Fredric Wertham's book 'Seduction of the Innocent' (1954), had brought EC Comics into dire straits. Since an American Senatorial Committee had deemed horror and crime comics "a danger to the youth", EC was forced to discontinue all of their titles in these genres. Only Mad was able to stay, since it was "just a humor magazine". Ironically, Mad's subversive satire influenced young readers far more than EC's horror comics and the editors were lucky that Mad was effectively their best-selling magazine. However, Harvey Kurtzman blamed William M. Gaines and Al Feldstein for the situation they had brought themselves in and wanted a higher financial share. When his demand wasn't met, he left, taking several Mad cartoonists with him, including the loyal Will Elder.

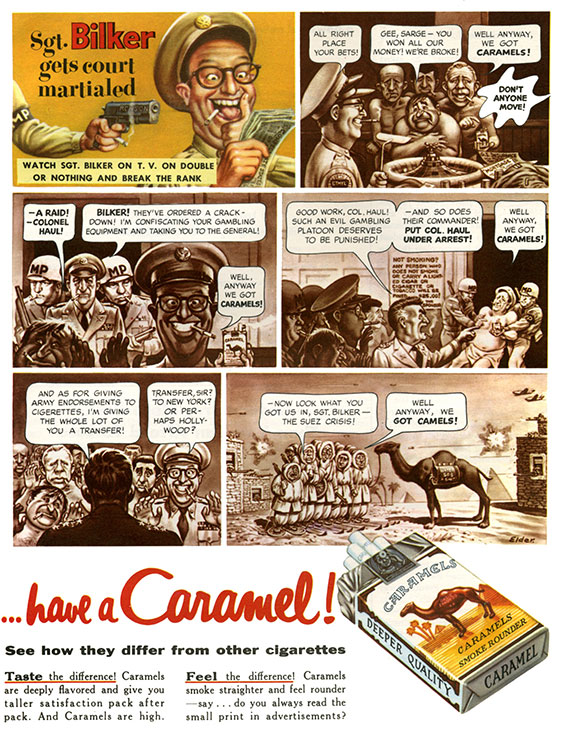

Kurtzman had received a creatively satisfying offer from none other than Hugh Hefner, chief editor of Playboy, at the time the most lucrative magazine in the world. Hefner was a fan of Kurtzman's work and gave him the opportunity to create a new satirical magazine, Trump, of which the first issue rolled from the presses in January 1957. Again, it was comparable to Mad, only with a more luxurious format and stronger emphasis on sex jokes. In the first issue, Will Elder drew a western parody, 'The Fastest Gun There Is', based on a Glenn Ford B-western, and a spoof of Al Capp's 'Li'l Abner', both scripted by Kurtzman. In the second issue, he illustrated a parody of Arthur Miller's play 'Death Of A Salesman', scripted by future comedy film director Mel Brooks. In the same issue, Elder also mocked the old-fashioned Sunday comic for the entire family 'Eddy Cat. Etiquette' ('Eti Quette') and a Camel cigarettes advertisement ('Carmel') starring comedian Phil Silvers as Sgt. Bilko. Hugh Hefner liked the look of this 'Camel' parody so much that later, when Kurtzman and Elder later made the comic 'Little Annie Fanny' for him in Playboy, he requested them to use the same painted style.

Unfortunately, Trump far exceeded its budget, right when Playboy's major distributor, American News, faced bankruptcy. Hefner was forced to make some financial cuts to survive, including discontinuing Trump after only two issues. Elder had prepared an illustration for the never-released next issue, depicting an elderly couple feeding frogs and birds to carnivorous plants, all drawn in the gentle style of Norman Rockwell.

Camel advertising spoof from Trump #2, spoofing the cigarette brand 'Camel', depicting 'Sgt. Bilko' actor/comedian Phil Silvers and referencing the 1956 Suez Crisis, when Egypt closed the Suez Channel, causing economic problems and British-French-Israeli military "intervention" in Egypt.

Humbug

In 1957, Harvey Kurtzman rushed out a new satirical magazine, Humbug, which Hugh Hefner no longer financed, but did provide advertising space for in Playboy. Its style was more political than its predecessor, though it did feature the familiar spoofs of ads, TV shows and films. Among Elder's most notable contributions were a parody of the TV game show 'Tell the Truth' (issue #6, January 1958) and a 'Frankenstein' pastiche he personally was most proud of (issue #7, February 1958). He even received a letter from two students from Brown University in Rhode Island, who complimented him with his adaptation of Mary Shelley's classic gothic novel being closer to the source material than the Hollywood movies. Elder also drew parodies of the films 'Baby Doll' (issue #1, August 1957), 'Jailhouse Rock' (issue #8, April 1958), 'Old Yeller (issue #10, June 1958) and 'Rodan' (issue #11, October 1958). While Humbug lasted 11 issues, its small size made it difficult to spot in stores and it eventually was also discontinued. Most of the cartoonists then returned to Mad, which had remained a success after Kurtzman's departure.

'Goodman Beaver Goes Playboy'.

Help! (Goodman Beaver)

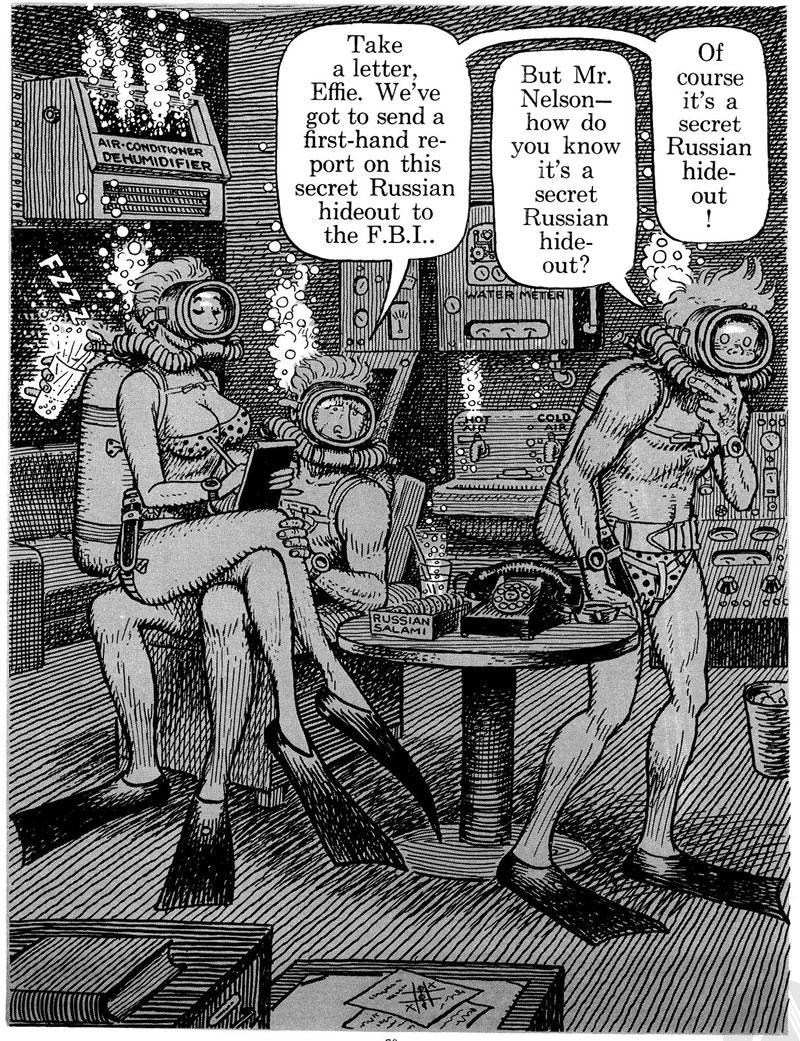

In August 1960, Harvey Kurtzman launched yet another satirical magazine, Help!, relying more on photo collage spoofs and fumetti (photo comics) than actual hand-drawn comics. The most notable exception was Kurtzman and Elder's 'Goodman Beaver' feature, which debuted in issue #10 (May 1961). Goodman was a character who originated in Kurtzman's previous graphic novel Jungle Book, but was now recast as a young idealist typically finding himself in an odd location, asking questions about the madness surrounding him. In one episode he goes to Africa, where he confronts Tarzan with his supposed white colonial attitudes towards the natives. In 'Goodman, Underwater' (May 1962), Goodman meets a Don Quixotesque underwater crimefighter who fights invisible enemies. The entire story is done in the style of Gustave Doré's illustrations of Cervantes' famous novel. Other episodes brought Goodman in contact with Marlon Brando and a disillusioned Superman. In 'Goodman Goes Playboy' (issue #13, February 1962), the teenager meets Archie from Archie Comics who has now succumbed to the Playboy style. Archie and his friends turn out to have signed a pact with "the Devil", AKA Hugh Hefner. As many follow their example, Goodman wonders whether he "should leave to find a place where the dark forces aren't closing in... where honor is still sacred and where virtue triumphs?" But he quickly changes his mind: "Maybe I should sign up."

While Hefner himself enjoyed the parody, Kurtzman was sued by Archie Comics publisher John Goldwater. The case was settled out of court, with Help! running an apology in their next issue and paying 1,000 dollars in damage. Within a year, 'Goodman Goes Playboy' was reprinted in Executive Comic Book, though Elder took the precaution of modifying the artwork. Archie Comics nevertheless sued again and in an out-of-court settlement received the copyright to the story, ensuring it could never be reprinted in its entirety. In August-September 2004, it was reprinted in the 262th issue of The Comics Journal, since it already entered public domain as Archie Comics had forgotten to renew its copyright over the strip.

'Little Annie Fanny', by Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman.

Little Annie Fanny

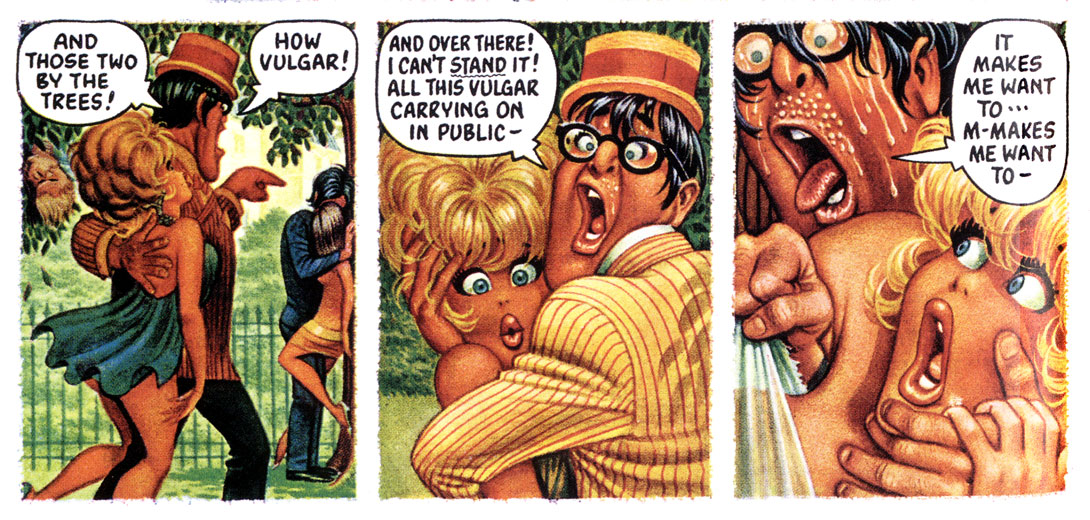

The irony about 'Goodman Goes Playboy' was that Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman also signed up with Playboy. After Trump folded, editor Hugh Hefner still wanted to help the cartoonists out. He asked them to create a monthly comic strip in the style of 'Goodman Beaver'. Kurtzman took the same concept, but made the protagonist a big-breasted young woman, to appeal more to the magazine's readers. Starting October 1962, 'Little Annie Fanny' appeared on the final pages of each issue of Playboy magazine. Her name is a pun on the English word for a women's behind ("fanny"), while the title, logo and various side characters nod to Harold Gray's classic comic series 'Little Orphan Annie'. Fanny is often seen in the presence of her boyfriend/protector Sugardaddy Bigbucks, his assistant The Wasp and bodyguard Punchjab. Her mother Ruthie and best friend Wanda Homefree are also recurring characters. Just like Goodman Beaver, Fanny isn't terribly bright. The dumb blonde often finds herself in situations beyond her comprehension, which typically lead to her being stripped naked. But even then, she is utterly oblivious to how many horny men (and occasionally women) want to leer at her. Kurtzman and Elder were directly inspired by a similar comic about a sexy girl with frequent wardrobe malfunctions, Norman Pett's 'Jane'.

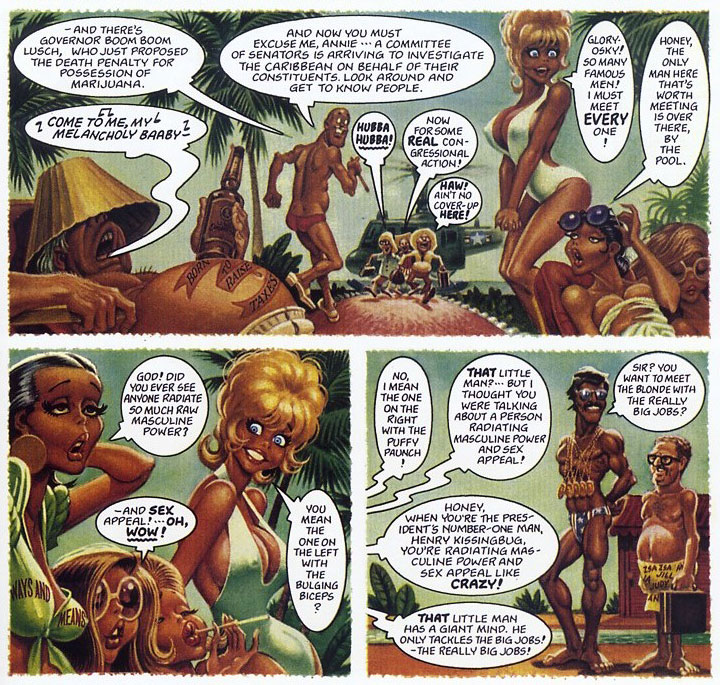

'Little Annie Fanny'. The two men in bathing suits in the third panel are caricatures of Olympic swimming champion Mark Spitz and U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

'Little Annie Fanny' was the first comic strip feature in Playboy. Just like the magazine's single-panel erotic cartoons, it appeared in soft colors. Hefner paid double to render it in the same expensive four-color process printing. At his insistence, each panel was fully painted in oil, tempera and watercolor but without ink, which added to its gentle and lavish look. Since it was such a time-consuming job, Elder was often assisted by Russ Heath and Frank Frazetta, while other cartoonists like Jack Davis, Arnold Roth, Paul Coker, Larry Siegel, William Stout and Al Jaffee occasionally helped out to reach the deadlines. Despite its naughty comedy, Kurtzman's familiar satirical hallmarks were also present. Fanny and her friends often encounter real-life politicians and activists (Khomeini, Ralph Nader, Jim Bakker), novelists (J.D. Salinger, Philip Roth), Hollywood actors (Marlon Brando, Arnold Schwarzenegger), TV hosts (Howard Cosell), sports figures (Bobby Fischer) and pop stars (Elvis Presley, The Beatles, Alice Cooper). Throughout the decades, the feature satirized all kinds of trends and social changes, from advertisements, hippies, feminists and streaking (naturally!) to disco and personal computers. Certain episodes parodied popular TV shows (Jim Henson's The Muppets, 'The Love Boat') and movies (James Bond, Indiana Jones, E.T.).

For 26 years, 'Little Annie Fanny' was a mainstay in Playboy's pages, and provided Elder and Kurtzman with a well-paid steady income. The feature was so popular that rival nude magazine Penthouse ran a similar comic strip: Frederic Mulally and Ron Embleton's 'Oh, Wicked Wanda' (1969), though with a lower budget and different tone. Hustler's answer to both comics was James McQuade's 'Honey Hooker'. In Belgium, Yves Duval and Dino Attanasio's 'Candida' (1968), and in Spain Blas Gallego's 'Dolly' were obviously inspired by Fanny.

'Little Annie Fanny'.

Nevertheless, 'Little Annie Fanny' has been a highly polarizing comic strip among Kurtzman fans. Some rank it among his best satires, others consider it too pornographic, sexist and formulaic. After all, Fanny's wardrobe had to malfunction every episode. The artists didn't even have total creative control over the end product either. Hefner checked every script and lay-out personally. He would veto certain elements, explain why they didn't fit in his magazine and even suggested improvements. To Kurtzman this was all very demoralizing and humiliating. He was also aware that he was now working for the same kind of a major corporation he used to lampoon. Even worse, he was promoting cheap marketing techniques, namely soft porn. But the artist needed the money. All his other projects went nowhere and above all he had a family to support, including an autistic son whose treatment cost a lot of money. 'Little Annie Fanny' kept going until September 1988, when Kurtzman was shocked to learn that he didn't own the rights to the series. He discontinued the feature immediately. Dark Horse Comics collected all episodes in two volumes. In 1998, 'Little Annie Fanny' was revived in Playboy by Ray Lago and Bill Schorr.

Promotional artwork for movies.

Additional work

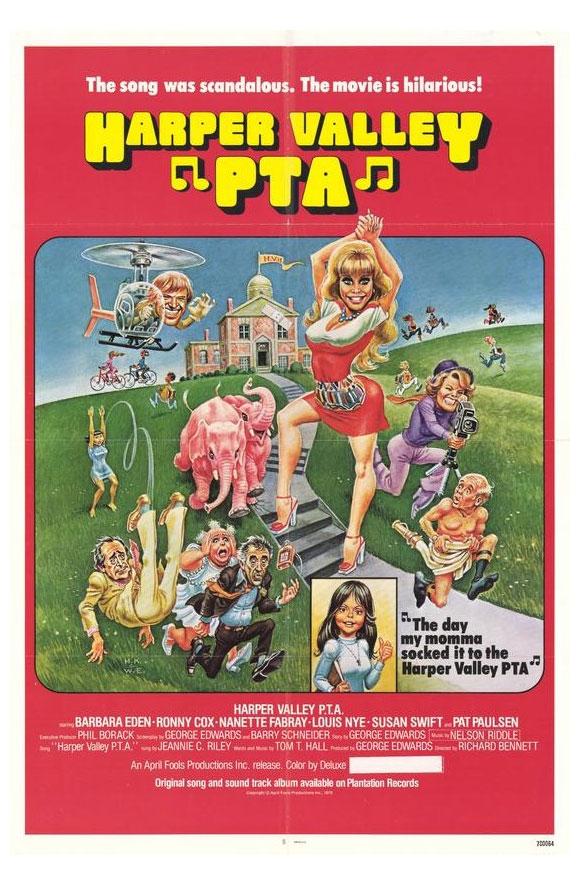

As most of the post-Mad humor magazines were short-lived, Will Elder additionally did freelance artwork for advertisements and magazines. For one, he contributed to a great many other satirical magazines of the late 1950s and 1960s, namely Cracked (1958-1959), Loco (1959) and Pow (1966). During the 1960s, Elder illustrated articles for Pageant and worked on advertisements for Transfilm-Wylde TV Studios (1962-1963). In 1967, Elder contributed a titleless one-page cartoon to Wallace Wood's alternative comic magazine witzend, printed in the second issue. Between 1976 and 1985, Elder illustrated several covers and ads for TV Guide. He also made illustrations for the Saturday Evening Post and designed film posters to advertise 20th Century FOX pictures, for instance 'Mr. Hobbs Takes a Vacation' (1962) with James Stewart. In 1987-1988, he drew illustrations for Denis Kitchen's underground comic SNARF. In 1993, he drew a cover for The New Yorker, as well as a graphic "in memoriam" for Harvey Kurtzman.

Return to Mad

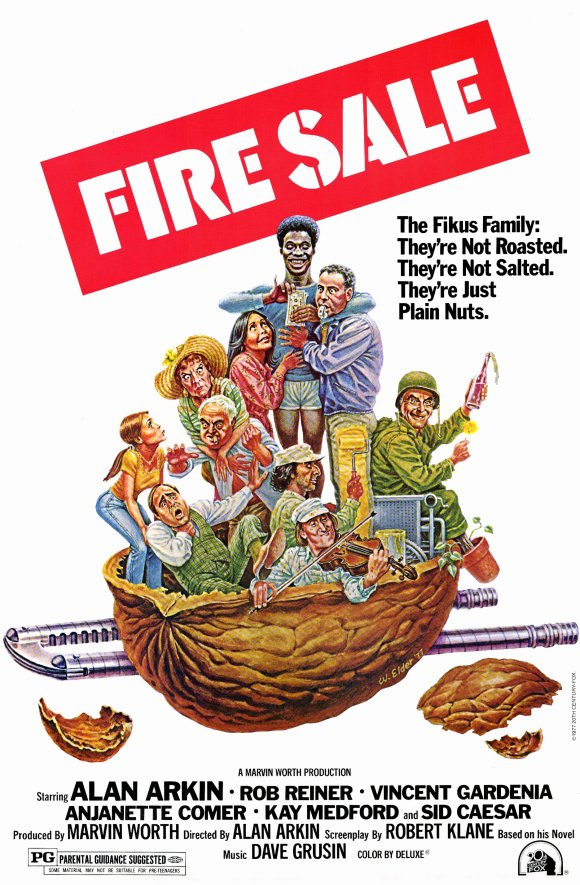

Between 1984 and 1989, Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman returned to Mad. They designed the covers of issues #259 (December 1985), #261 (March 1986) and #268 (January 1987) and mostly provided advertisement parodies on the back cover, printed in color. However, they also illustrated comics and articles by Mad's regular writers, such as a parody of 'Wheel of Fortune' (issue #266, October 1986, with Dick DeBartolo). In the recurring features 'Mad's ... of the Year' and 'Mad Visits...', Kurtzman, Elder and Lou Silverstone tackled a banana republic dictator (issue #270, April 1987) and an organ transplant hospital (issue #272, July 1987). Another memorable entry was 'How to Pick Up Guys' (issue 265, September 1986), co-scripted with Arnie Kogen, in which girls use suggestive pick-up lines thematically fitting to the location where they spot attractive men.

Cover illustration for Mad issue #268 (January 1987), depicting Sigourney Weaver.

Graphic contributions

In 1944, Will Elder illustrated a press book, sent around to theater owners, promoting 'Ernie Tubbs's Singing Cowboys' (1944). He also designed the cover for the paperback edition of Shepherd Mead's 'How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying' (Ballantine, 1955) and Oscar Brand's 'Folk Songs for Fun' (Berkeley, 1961). He livened up Chuck & Di's Cut-out Dolls book (1983) and, in 1987, he made a lithograph depicting E.C. Segar's Popeye and Olive Oyl getting married, with many 'Thimble Theater' cast members being present during the ceremony.

Recognition

In 2000, Will Elder received the Inkpot Award. In 2003, he was inducted into the Comic Book Hall of Fame and, posthumously, in the Harvey Awards Hall of Fame (2019).

Redrawn version of the illustration in the style of Norman Rockwell, intended for the third issue of Trump. Released as a poster by Starbur Graphics in 1985.

Legacy and influence

In 1988, after they had terminated 'Little Annie Fanny', both Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman retired. For the remainder of his life, Elder mostly made paintings and illustrations. In 1999, he underwent triple bypass surgery and was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. In 2005, after his wife passed away, Elder was brought to a rest home in Rockleigh, New Jersey, where he died in 2008, at age 86.

Will Elder is still rediscovered by new generations of humorous comic artists. His talent is widely recognized, though Al Feldstein once said that Elder, despite being a "hysterical individual", spent too much time under Kurtzman's wings: "Not that he isn't a fantastic humor artist (…), it's just that it isn't Willy Elder by himself. He's Willy Elder and Harvey Kurtzman and that really isn't the end. I never really saw Willy Elder by himself develop and I think that this is a terrible waste of talent."

In the United States, Elder was a strong influence on Tom Bunk, Charles Burns, Daniel Clowes, Robert Crumb, Sophie Crumb, Evan Dorkin, Mort Drucker, Terry Gilliam, Larry Gonick, Rick Parker, Rich Powell, Tom Richmond, Jim Scancarelli, Gilbert Shelton, Art Spiegelman, Bhob Stewart, Steve Stiles, William Stout, Angelo Torres, Skip Williamson, Wallace Wood and Jim Woodring. Terry Gilliam once said that in his animated cartoons and live-action films, he always has one part of him that he calls his "Elder side", wanting to cram in as much stuff in as possible. In Europe, Elder has followers in France (Gotlib, René Pétillon, Wolinski), The Netherlands (Theo van den Boogaard, Charles Guthrie, Hanco Kolk) and the United Kingdom (Dave Gibbons, Mark Stafford). In his daily newspaper comic 'S1ngle', Kolk used the same soft-painted color technique as in 'Little Annie Fanny'.

Books about Will Elder

For those interested in Elder's life and career, Gary Groth & Greg Sadowksi's 'Will Elder: The Mad Playboy of Art' (Fantagraphics, 2003) and 'Chicken Fat' (Fantagraphics, 2006), are highly recommended.

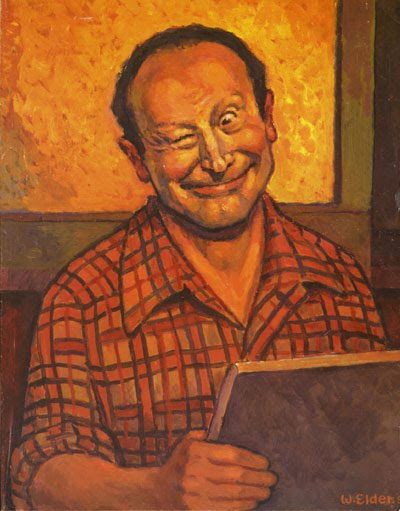

Self-portrait.