Cover of Mad Magazine issue #1 (October 1952), drawn by Harvey Kurtzman.

Harvey Kurtzman was an American comic creator, widely considered as one of the most influential satirists of his time. As the co-founder of Mad (1952-2019), he scripted comics which spoofed and twisted all conventions, clichés and lies in mass media, advertising and politics. Even though he was Mad's chief editor during only the first four years, his run is widely regarded as its finest moment. He established Mad's house style, which his successors continued for decades. Countless humor magazines have been inspired by Mad, including Kurtzman's own short-lived attempts Trump (1957), Humbug (1957-1958) and Help! (1960-1965). Kurtzman's longest-running comic feature was the erotic satirical comic 'Little Annie Fanny' (1962-1988) in Playboy magazine, made with his most prominent collaborator Will Elder. Kurtzman showed a more serious but equally poignant side of himself in the gritty and realistic comic books 'Two-Fisted Tales' (1950-1955) and 'Frontline Combat' (1951-1954), which depicted the horrors of warfare in a time when most other war comics didn't. Overall, Kurtzman's work exposed mainstream shallowness and hypocrisy. His playful subversiveness and experimental nature not only influenced many satirical comics, but laid the foundations for the underground comix movement and other post-war adult comics.

Early life

Harvey Kurtzman was born in 1924 in Brooklyn as the son of Russian-Ukrainian Jewish parents, although his father had converted to Christian Science. When Harvey was four, his father refused to treat a bleeding ulcer and just prayed to be cured, as his church taught him. After his subsequent death, Harvey's mother placed her children in an orphanage for three months, until she found a job as a hatmaker. She remarried to a brass engraver who was active in trade unions, and who also encouraged Harvey Kurtzman to pursue his artistic interests. On Monday mornings, the boy went through people's garbage cans to search thrown-away copies of yesterday's papers, just to collect the Sunday funnies. He drew his own comics in chalk on the pavements of the Brooklyn streets, and named his characters 'Ikey and Mikey' after Rube Goldberg's 'Mike and Ike'. Besides Goldberg, Kurtzman's graphic influences were Will Eisner, Milton Caniff, Chester Gould, Harold Foster, E.C. Segar, Alex Raymond, Al Capp, Thomas Nast, Wilhelm Busch, Caran d'Ache, H.M. Bateman, Bill Holman and V.T. Hamlin. His love for parody and satire was mostly shaped by Eisner's 'The Spirit' and Capp's 'Li'l Abner'. The anarchic comedy of The Marx Brothers and self-reflexive cartoons of Tex Avery and Looney Tunes influenced him as well. Kurtzman also studied the engravings of Gustave Doré, particularly his use of light and shading. In terms of magazines, he enjoyed reading Yale Record, The Harvard Lampoon, Judge and Punch.

'Mr. Risk, from Super-Mystery' v3#5 (July 1943).

Early career

Since Harvey Kurtzman showed intelligence beyond his peers, he was allowed to skip a grade. As a twelve year old, he applied for a job at the Walt Disney Studios, but was predictably rejected. Two years later he won a cartooning contest, which led to his first publication in Tip Top Comics issue #36 (April 1939). After winning the John Wanamaker Art contest, he received a scholarship for the High School of Music & Art in New York. There he met fellow students and future collaborators such as Al Jaffee, Will Elder, John Severin and Al Feldstein. After graduation in 1941, he attended Cooper Union for about a year, but left to become a cartoonist. In Martin Sheridan's book 'Classic Comics and their Creators', Kurtzman read that Alfred Andriola offered help to struggling cartoonists, but when he got in touch, Andriola bluntly told him to "give up cartooning". Slightly discouraged, Kurtzman did manage to become an assistant in Louis Ferstadt's studio by June 1942. Between 1942 and 1943 he assisted on Ferstadt's comic book production for Gilberton ('Classic Comics'), Ace Magazines (features like 'Lash Lightning', 'Magno & Davy', 'Mr. Risk') and a daily comic strip called 'Li'l Lefy' in The Daily Worker. On the side, Kurtzman created crossword puzzles for Martin Goodman's publishing company. At Quality Comics, Kurtzman showed hints of his later genius in issue #24-27 of Police Comics, when he succeeded Al Stahl on 'Flatfoot Burns' (1943-1947), a silly and tiny detective who enjoyed three humorous adventures under Kurtzman's pen, before Milt Stein took over.

'Black Venus' (Contact Comics #11 (March 1946).

World War II

In 1943, during World War II, Kurtzman was drafted, but remained stationed in the United States. In his spare time he illustrated military flyers, posters, instruction manuals, newsletters and papers. The comic artist and packager L.B. Cole offered him a job to draw the superhero comic 'Black Venus' for publisher Orbit Publications. Some other early cartoons and comics were published in several North Carolina magazines, while three gag cartoons by Kurtzman's hand appeared in Yank, the official Army magazine. The majority of his production during this period were unexceptional stories and jokes, but allowed him to work on both his writing and graphic style.

Hey Look! and other late 1940s/early 1950s comics

Back in civilian life, Harvey Kurtzman joined Charles Stern and Will Elder in starting a comics studio in 1947, the Charles William Harvey Studio. Based at 1151 Broadway in New York City, they housed many future talents, mostly people who later became associated with Mad, such as John Severin and Dave Berg, but also foreigners like future 'Astérix' creator René Goscinny. A still unknown Stan Lee offered Kurtzman a low-paid job at Timely Comics (nowadays Marvel), where he created the gag comic series 'Hey Look!' (1946-1949) as a filler for their several humor books. The comic strip stars two nameless characters, one tiny, the other tall. Already Kurtzman's cartoony and energetic style jumps off the page. Many episodes feature self-reflexive comedy, for instance when the duo rips up the final panel because the reader isn't laughing. In another gag, they complain about their coffee, which "tastes like black ink." While by no means a hit series, Kurtzman's future wife Adele (one of Timely's proofreaders) managed to keep the comic strip running by fixing the results of a reader's poll in his favor. Episodes of 'Hey Look!' were later reprinted in Mad issues #7 (October 1953) and #8 (December 1953). In 1998, Vincent Waller made an animated short adaptation of Harvey Kurtzman's comic feature 'Hey Look!' for the Nickelodeon anthology series 'Oh Yeah! Cartoons'.

Stan Lee gave Kurtzman more assignments, including the funny animal comic 'Pigtales' (1946-1947) and the humorous family comic 'Rusty' (1949), which Lee scripted for him. Between March and June 1948, Kurtzman's Sunday comic 'Silver Linings' (1948) appeared in the New York Herald Tribune, which was basically a compact version of 'Hey Look!'. Kurtzman also published gag comics like 'Egghead Doodle', 'Genius' (later revived as 'Sheldon' in Kurtzman Komix) and 'Pot-Shot Pete' for comic books by Timely Comics, National Periodicals, Toby Press and Parents' Magazine Press. Of all these, 'Pot-Shot Pete' was the most memorable. A funny western parody ridiculing various platitudes, it appeared in American Western (February/March 1950) and was later reprinted in issue #4 (1950) of Jimmy Wakeley and John Wayne Adventures #5 (1950) and issues #15 (September 1954) and #18 (December 1954) of Mad Magazine. In addition, Kurtzman made some children's books for Kunen, some in collaboration with René Goscinny: 'Round the World', 'Hello Jimmy', 'The Little Red Car' and 'The Jolly Jungle'. He also wrote two episodes of Dan Barry's 'Flash Gordon' (1952-1953), co-illustrated by Frank Frazetta, and contributed wonderfully wacky and crowded cartoons to magazines like Varsity and College Life.

'Follow that girl!' (part of a spread for Varsity Magazine).

EC Comics

Most of Kurtzman's early comics paid bills, but didn't satisfy his creativity in the long term. Their formulaic content created a strong urge to break away from the norm. Around this time he read Charles Biro and Bob Wood's 'Crime Does Not Pay' (1942-1955), a monthly crime comic book series with quite violent and risqué content. It had less in common with the infantile superhero comics that were in vogue at the time and more with the hard-boiled detective novels by James M. Cain, Dashiel Hammett, Raymond Chandler and Mickey Spillane. It inspired Kurtzman to go into a similar direction. At Educational Comics, or EC Comics as it was popularly known, he found the ideal platform for his innovative ideas. Kurtzman's first assignment for EC was an educational cowboy story, 'Lucky Fights It Through' (1949), printed on a pamphlet to warn readers about syphilis. As the 1950s rolled on, EC's chief editors William M. Gaines and Al Feldstein started publishing fantasy, horror and war comics that stood out because of their captivating thrills and gruesome imagery. Several of these early sci-fi and horror books of EC's "New Trend" line featured Kurtzman art and plots, for instance 'Vault of Horror', 'Weird Fantasy' and 'Weird Science'. However, Kurtzman wasn't as interested in fantastic horrors as in real-life horrors, and was allowed to edit his own war/adventure magazine.

'Horror in the Night' (The Vault of Horror #12).

Two-Fisted Tales & Frontline Combat

In November-December 1950, EC Comics editors William M. Gaines and Harvey Kurtzman published the first issue of 'Two-Fisted Tales', which was followed in July-August 1951 by a sister title, 'Frontline Combat'. Both were bi-monthly comic books featuring war comics, edited by Kurtzman. Most of the storylines were inspired by World War II and the then ongoing Korean War, though some went further back in time, depicting Ancient Rome, the U.S. Revolutionary War, the Napoleonic Wars, the U.S. Civil War and the 19th-century wars against Native Americans. Instead of heroic epics, Kurtzman's comics depicted warfare as a brutal, gritty, devastating experience. Soldiers are just ordinary, frightened and insecure men trying to survive in harsh and chaotic circumstances. Death and destruction are everywhere. Even when a battle is won, characters wonder what they have achieved. In the early 1950s, Kurtzman's comics were a remarkable and brave artistic statement. At the time, most media, especially in the U.S., idealized warfare and dumbed it down as a battle between "good vs. evil". In 1980, Kurtzman explained his line of thought: " (...) Everything that went before Two-Fisted Tales had glamorized war. Nobody had done anything on the depressing aspects of war, and this, to me, was such a dumb (...) terrible disservice to the children."

'Air Burst!' (Frontline Combat #4).

The very idea of questioning the heroism of American G.I. was controversial. Kurtzman even took the unprecedented move to give "the enemy" humanity. In 'Air Burst!' (Frontline Combat, issue #4, January-February 1952), an entire story is told from the viewpoint of North Korean soldiers. In his personal masterpiece 'Corpse On The Imjin' (Two-Fisted Tales, February 1952), the story kicks off with the image of a dead soldier floating down a Korean river. An American soldier notices the corpse and wonders how he might have died. Suddenly he is attacked by a Korean soldier and both engage in hand-to-hand combat for their lives. All glamor is absent: two men just beat each other up to exhaustion. In his narration Kurtzman sarcastically notes: "Where are the wisecracks you read in the comic books? Where are the fancy right hooks you see in the movies?" Eventually the American manages to push the Korean in the river and, in a bone-chilling sequence, drowns him. The story ends with the Korean corpse floating down the river, but now the previously nameless body has been humanized. His cause of death is no longer a question, nor an abstraction. Even the American G.I. is shocked. As Kurtzman's gut-punching narration states: "Suddenly your mind is quiet and your rage collapses! The water is very cold. You're tired... your body is gasping and shaking weak... and you're ashamed!" In his 2015 biography book 'Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Created Mad and Revolutionized Humor in America', Bill Schelly discovered that J. Edgar Hoover of the FBI actually ordered an investigation of Kurtzman's war comics because he considered them "anti-patriotic".

'Frontline Combat' #7(July-August 1952) and 'Two-Fisted Tales' #25 (January-February 1952).

Kurtzman knew from first-hand experience that real-life combat had nothing to do with Hollywood or infantile comic books. He went through great lengths to research his stories, interviewing soldiers, flying along in a rescue plane and even ordering his assistant Jerry DeFuccio to travel inside a submarine. Kurtzman illustrated a few stories in the series himself, such as the Two-Fisted Tales stories 'Conquest' (issue #18, November-December 1950), 'Jivaro Death' (issue #19, January-February 1951), 'Pirate Gold' (issue #20, March-April 1951), 'Search' (issue #21, May-June 1951), 'Kill' (issue #23, September-October 1951), 'Rubble' (issue #24, November-December 1951) and 'Corpse On the Imjin' (issue #25, January-February 1952). For Frontline Combat he drew 'Contact!' (issue #2, September-October 1951), 'Prisoner of War!' (issue #3, November-December 1951), 'Air Burst!' (issue #4, January-February 1952) and 'Big 'If'!' (issue #5, March-April 1952). For most of the others, he wrote the narratives and sketched the storyboards, while the finished artwork was provided by the regular EC artists Dave Berg, Gene Colan, Johnny Craig, Reed Crandall, Jack Davis, Will Elder, Ric Estrada, George Evans, Russ Heath, Bernard Krigstein, Joe Kubert, John Severin, Alex Toth and Wallace Wood. On occasion, Jack Davis, Colin Dawkins, Jerry DeFuccio, George Evans, John Putnam and Wallace Wood helped out too.

'Corpse On The Imjin' (Two-Fisted Tales, February 1952).

'Two-Fisted Tales' and 'Frontline Combat' were Kurtzman's first signs of maturity as an artist. While his own artwork was less detailed than that of his colleagues, Kurtzman used his limitations to his advantage. He had a strong sense of composition and readability. His thick, pitch black shaded lines added to the grim atmosphere. Panels instantly grab the attention with clearly defined character poses and well-balanced compositions. However, the stories took almost a month to prepare, while most other EC titles were written in a week. Kurtzman's war titles also significantly sold less than EC's other titles, so publisher Bill Gaines suggested making a humorous comic book instead, which would be "easier" to create. As Kurtzman focused his attention on this new project, he let the other artists draw new episodes for the war titles, although he continued to keep creative control through his lay-outs and directions.

The final issue of Frontline Combat appeared in January 1954, and the last Two-Fisted Tales rolled off the presses in February 1955. In 1991, Richard Donner, Tom Holland and Robert Zemeckis made the TV film 'Two-Fisted Tales' which, apart from the title, had little in common with the comics. In 1993-1994 Dark Horse Comics published two issues of a follow-up named 'Harvey Kurtzman's The New Two-Fisted Tales' (Dark Horse, 1994), with scripts and artwork by Don Lomax, Wayne Vansant, Jessica Steinberg, Spain Rodriguez, Robert Hambrecht, Leo Durafiona and John Garcia.

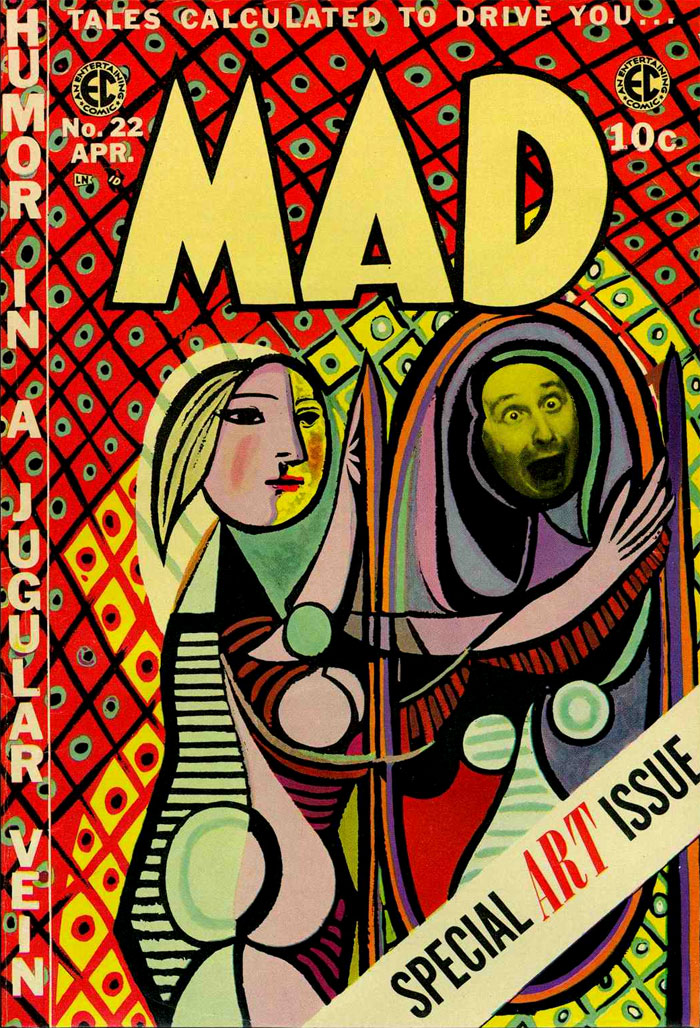

Cover illustrations for Mad #9 (March 1954) and #22 (April 1955).

Mad Magazine

In October 1952, the first issue of Mad saw print. Even though this humor comic was supposed to be an "easier" job, Kurtzman continued the same ambitions he had pushed with his war comics: expose the lies and clichés in mainstream culture. The workaholic was basically in charge of the entire content, except for some articles co-written with Jerry DeFuccio. Otherwise, Kurtzman penned every column, answered letters from readers and scripted all comics. As an illustrator he designed most of the covers, including that of the very first issue. He often signed his work by turning the last syllable of his name into a stick figure, or "man". The only comics in Mad by his own hand were reprints of 'Hey Look!' and 'Pot-Shot Pete', the rest of the material was illustrated by other EC staples like Jack Davis, Will Elder, Russ Heath, Bernard Krigstein, John Severin and Wallace Wood, who were primarily used to drawing realistic and serious comics. Some, like Heath, Krigstein and Severin, felt comedy wasn't their thing and only made a few contributions. Others, like Davis, Wood and especially Elder, discovered their potential and remained associated with Mad for decades. Basil Wolverton was only hired to draw grotesque and gross portraits, like his iconic cover of issue #11 (May 1954), which lampooned Life Magazine's 'Beautiful Girl of the Month', but with an ugly hag instead. Yet his impact was such that his work is still fondly remembered decades later. Al Jaffee came on board from issue #28 (July 1956) on and stayed with Mad right until its final issue in August 2019.

The first two issues of Mad were general parodies of comics genres. From the third issue (January 1953) on, targets became more specific, with 'Dragnet' and 'The Lone Ranger' as prime examples. Kurtzman and Wallace Wood's spoof of Siegel & Shuster's 'Superman' ('Superduperman', issue #4, April 1953) is often credited as Mad's breakthrough. Clark Kent is turned into a pathetic geek, whom Lois Lane arrogantly pushes around. After several funny twists on the familiar 'Superman' tropes and a guest appearance by C.C. Beck and Bill Parker's 'Captain Marvel', Kent reveals his true identity to Lois. However, she doesn't care that he is Superman, because "once a creep, always a creep." American audiences have always loved pop culture parodies and 'Superman' was the best-selling comic at that time. As such, many readers were familiar with the original, but most had never seen such an anarchic and thorough deconstruction of the franchise. Mad soon gained a cult following and sales rose with every issue. From issue #10 (April 1954) on, the bi-monthly title appeared monthly. At Kurtzman's request, it changed from a comic book into an actual magazine from its 24th issue (July 1955) on, with a larger format, more pages and better printing quality. This issue instantly sold out and had to be reprinted, something unprecedented in the magazine business. Paperback collections with reprints were launched in November 1954 and also became bestsellers.

'Woman Wonder' (Mad #10), art by Will Elder.

In the early 1950s, Mad had a monopoly regarding parodies of other comics. No other magazine directly satirized other artists' creations in full six-page stories. During this classic period, Kurtzman and his artists directly lampooned comics like Chuck Cuidera, Bob Powell and Will Eisner's 'Blackhawk' (issue #5, June 1953), Milton Caniff's 'Terry and the Pirates', Hal Foster's 'Tarzan' (issue #6, August 1953), Zack Mosley's 'Smilin' Jack' (#7, October 1953), Bob Kane's 'Batman' (#8, December 1953), Dave Breger's 'G.I. Joe' , William Marston and Harry G. Peter's 'Wonder Woman' (#10, April 1954), Alex Raymond's 'Flash Gordon' (issue #11, May 1954), Bob Montana's 'Archie' and Ed Dodd's 'Mark Trail' (issue #12, June 1954), Hal Foster's 'Prince Valiant' (issue #13, July 1954), Lee Falk and Phil Davis' 'Mandrake the Magician' and Jack Cole's 'Plastic Man' (issue #14, August 1954), Frank King's 'Gasoline Alley' (issue #15, September 1954), George McManus' 'Bringing Up Father' (issue #17, November 1954), Walt Disney's 'Mickey Mouse' (issue #19, January 1955), Rudolph Dirks' 'The Katzenjammer Kids' (issue #20, February 1955), E.C. Segar's 'Popeye' (issue #21, March 1955) and Walt Kelly's 'Pogo' and Robert Ripley's 'Believe It Or Not' (issue #23, May 1955).

As a massive comics reader since childhood and someone who once scripted and drew formulaic heroic adventure comics in the past, Kurtzman knew his targets by heart. Some he liked, others, like 'Little Annie Rooney' and 'Archie Comics', he utterly loathed. But even with his favorite series, his main annoyance were its tired clichés. In Mad he gave them a well-deserved anarchic twist. In his spoof of 'Archie', the self-described "typical American teenager" is basically a smug teenage delinquent who treats Betty like dirt and claims Veronica's beauty can't compare to Betty, even though the panel shows them striking the same poses, designs and personalities, only with a different hair color. In 'Katzenjammer Kids' parody, Hans and Fritz' pranks against the Captain are pushed into an endless loop, with the same set-up repeating itself again and again. In Kurtzman's take on 'Bringing Up Father', the familiar joke where Jiggs is beaten up by his wife becomes a depressing display of painful domestic violence and their skinny dog dying from undernourishment. In Kurtzman's send-up of Disney comics, Horace Horacecollar is jailed for "not wearing gloves like all the other characters" and Clarabella Cow complains how difficult it is to find "these four-fingered kinds". Goofy reminds Donald Duck that he - once again- forgot to put on his pants, while Mickey eventually locks Donald up out of jealousy over his "bigger popularity".

Some parodies mixed several series into one thematically connected spoof, such as 'Miltie of the Mounties!' (issue #5, June 1953, illustrated by John Severin), which lampoons all sorts of novels ('Renfrew of the Royal Mounted'), radio series ('Sergeant Preston of the Yukon'), film serials ('Clancy of the Mounted', 'Perils of the Royal Mounted') and comic series ('Zane Grey's King of the Royal Mounted') about heroic Canadian mounties. In the same issue, the detective radio shows 'Martin Kane, Private Eye' and 'Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost Persons' were molded into the parody 'Kane Keen! - Private Eye', illustrated by Jack Davis. 'Little Orphan Melvin!' (issue #9, March 1954, illustrated by Wallace Wood) attacks both Harold Gray's melodramatic 'Little Orphan Annie' as well as Ed Verdier, Ben Batsford, Brandon Walsh and Darrell McClure's equally sappy 'Little Annie Rooney'.

Sometimes Kurtzman had so much fun ridiculing a certain series that he made a sequel. With Jack Davis, he laughed at 'The Lone Ranger' twice, in issue #3 (January 1953) and #8 (December 1953). The radio (and later TV show) 'Dragnet' was tackled as 'Dragged Net!' in respectively issue #3 (January-February 1954) and #11 (May 1954). 'Sherlock Holmes' was targeted as 'Shermlock Shomes!' in issue #7 (October 1953) and 'Shermlock Shomes in The Hound of the Basketballs!' (issue #16, October 1954). Kurtzman even spoofed the type of comics EC published. 'Outer Sanctum!' (issue #5, June 1953) is a send-off of 'Tales From the Crypt', complete with a scene where the door of the crypt slowly opens and the cryptkeeper eerily announces: "Welcome, I've been waiting for you... to fix my squeaking door!" In 'Murder the Husband/Story' (issue #11) Kurtzman recycled artwork from an earlier EC thriller comic and added inappropriate dialogue in several languages.

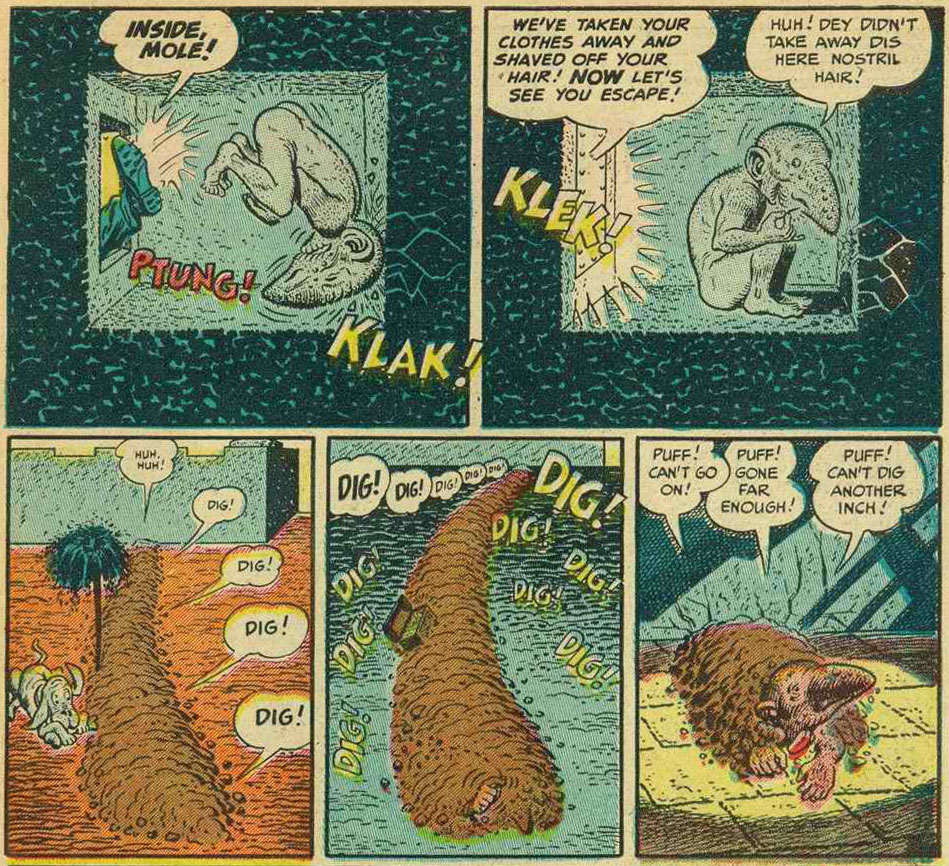

'Mole!' (Mad #22), artwork by Will Elder.

Mad: broader satire

Encouraged by Mad's high sales, Kurtzman broadened its satire. He took on novels ('Robin Hood', 'Treasure Island', 'Frankenstein'), poems ('The Raven', 'Casey at the Bat'...), films ('King Kong', 'Shane', 'Stalag 17') and TV shows ('What's My Line?', 'Howdy-Doody'). Particularly the film and TV spoofs caught on, since these were very current. The movies were still in theaters and television was a young medium, so in both cases Kurtzman explored uncharted territory. As the decades rolled on, Mad continued to parody comics from time to time, but with less regularity as their film and TV spoofs, which always remained their backbone. In every issue readers could find at least two or three. In Kurtzman's vicious parody of the children's puppet show 'Howdy Doody', the kids in the audience are way too loud and need to be disciplined. Howdy Doody, the star of the show, only appears in small segments and merely to aggressively shill his merchandising. While Mad didn't create political satire yet, their 'What's My Line?' spoof is notable for ridiculing senator Joseph McCarthy's anti-Communist witch hunts. He appears as a panel guest, accusing the host of being "a red-skin" (not a Communist, but a Native American). As he presents his "proof", it eventually turns out to be a manipulated photograph, ending "the show fit for the entire family" with a huge fight.

Starting with issue #24 (July 1955), the first magazine edition, Kurtzman found new targets by including parodies of advertisements. The idea had been pioneered by satirical magazines like Judge and Ballyhoo, but Mad perfected it. Their spoofs were so carefully crafted that they could pass for an actual ad, but those who read them more clearly, quickly notice sarcastic marketing talk and absurd premises. Up until 2001, Mad refused real-life sponsors because it allowed them to remain independent and keep ridiculing huge brands.

Thanks to Kurtzman, Mad magazine became an all-encompassing satire. He created funny and timeless observations of everyday life, with 'Newspapers!' (illustrated by Jack Davis, issue #16, October 1954), 'Restaurant!' (by Will Elder, same issue), 'Supermarkets' and 'Puzzle Pages' (Jack Davis, issue #19, January 1955). He also created original comics, like the classic 'Mole!' (art by Will Elder, issue #2, December 1952), which features a mole-like prisoner trying to escape jail in the most absurd ways. A straightforward, but nevertheless hilarious gag comic, it was later reprinted in issue #22 (April 1955).

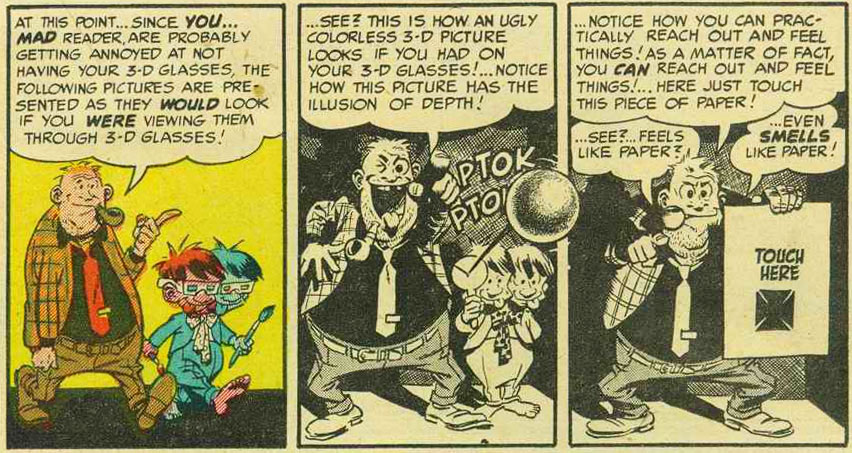

Kurtzman desperately wanted to avoid Mad becoming a formula itself. Each issue was unpredictable. Some covers depicted a gimmick, like a minuscule image (issue #13, July 1954) or all pages printed upside down (issue #17, November 1954). Others had a design that made it look as if Mad was a different publication, such as Life Magazine (issue #11, May 1954), a scientific mag (issue #12, June 1954), a newspaper headline (issue #16, October 1954), a sports race sheet (issue #19, January 1955), a school notebook (issue #20, February 1955) or an advertising page (issue #21, March 1955). To the casual customer in a store, these covers were very eye-catching and inclined the curious passer-by to page through them. Kurtzman continued the unpredictability inside. '3-Dimensions!' (illustrated by Wallace Wood, issue #12, June 1954) spoofed the novelty of 3-D comics, until the final page crumbles down, leaving only a blank page behind. Together with Wallace Wood, he made an entire story poking fun at onomatopoeia ('Sound Effects!', issue #20, February 1955) and slow motion ('Slow Motion!', Jack Davis, issue #21, March 1955). The most extreme experiment occurred in issue #22 (April 1955), where nearly every page shows "the artistic progress of Will Elder" with the help of collage & photo comics. Starting off with his supposed childhood, it continues to his professionalism as a veteran and eventual senility (a page where none of the sentences make sense).

'3-Dimensions!' (Mad #12), artwork by Wallace Wood.

Impact of Mad

In the 1950s, Mad was a revolution in comic history. Most other humor magazines, especially for children, were gentle, bland, clean-cut and family friendly. Mad's content, on the other hand, showed depraved scenes, hidden jokes, metafictional black comedy and was entirely iconoclastic. In the supposedly happy and carefree 1950s, Kurtzman's sophisticated comedy offered audiences a glimpse into the lazy and shameless corporate thinking that went behind every movie, TV show, comic and advertisement. Anyone who was fed up with mainstream hypocrisy and overexposure of certain media and trends, now had a publication that addressed it. In this sense, Mad was just as much an icon of 1950s teenage rebellion as 'The Catcher in the Rye', Marlon Brando and rock 'n' roll. In certain U.S. schools the magazine was banned, as many moral guardians looked down on it. Still, Mad didn't care: they even agreed. Kurtzman wrote sarcastic replies to letters from readers. Whenever someone felt a certain comic strip "went too far", he just insulted them. In many issues, Mad promoted itself as complete and utter trash that readers shouldn't spend their money on. They kept this attitude throughout their entire run and readers admired their audacity and honesty.

It cannot be denied that Kurtzman was Mad's spiritual father. He came up with their title, familiar logo, sarcastic attitude, self-deprecating comedy (like their long-running slogan: "25 cents, Cheap!") and invented their very style of parody. Each spoof opens with a huge splash panel covering half of the page, with the title displayed in large letters ending on an exclamation mark! The title and characters of a particular comic, film or TV show are changed into an incredibly lame pun - 'Popeye' becomes 'Poopeye', 'G.I. Joe' is bastardized to 'G.I. Shmoe', 'Prince Vaillant' transforms into 'Prince Violent'. Everything is drawn in a wacky style. The illustrator stacks every panel with funny background events, signs and random cameos of celebrities or pop culture characters. As the tale unfolds, all the formulaic writing of the original is hilariously exposed, eventually culminating to a twist ending. Kurtzman invented many running gags, such as the name 'Melvin' and puzzling expressions like "furshlugginer", "potrzebie", "schmuck", "veeblefetzer", "ecch" and "blecch", which were in fact derived from Yiddish or Russian-Ukrainian-Lithuanian words. He also pioneered one of Mad's longest-running features, 'Scenes We'd Like to See', which first appeared in issue #23 (May 1955), and provided hilarious twists to stale plot devices. Between issue #24 (July 1955) and #30 (December 1956) Kurtzman drew tiny little doodles in the margins of every cover, an idea that Sergio Aragonés revived in 1963 in his own 'Mad Marginals'.

Kurtzman commented on the witch hunt against comic books on the cover of Mad #16 (October 1954). Note the headline 'Comics Go Underground', which was the first time the term 'underground comix' was used, a full decade before it was coined to the genre.

Kurtzman's departure from EC

However, in the mid-1950s, psychologist Fredric Wertham launched a witch hunt against "dangerous comics", specifically targeting EC Comics because of their notoriously gruesome stories. EC's chief editors William M. Gaines and Al Feldstein were commissioned to testify in front of a Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency and forced to bow down to the industry's self-imposed censor brigade, the Comics Code. The scandal tainted EC so much that many people, including store owners, boycotted their company. In March 1955, they were forced to drop nearly all of their titles at the height of their success. Since Mad was "just a humor magazine", it escaped cancellation, which was a good thing, considering its tremendous sales. But the company was in serious debt and Kurtzman and Gaines' relationship became more strained. At Kurtzman's suggestion, Gaines and his mother invested private family money to pay off their debts and took a different distributor. This saved both EC as well as Mad, but Kurtzman still blamed their horror and mystery comics for bringing the company into this financial mess, which also seriously restricted what he wanted to do in Mad's pages. Gaines, on the other hand, felt that Kurtzman's perfectionism often made him miss deadlines. Eventually, Kurtzman asked for a 51 percent share in the company, which he naturally didn't get. As such, he left after issue #31 (February 1957), taking several of Mad's cartoonists with him. Gaines let Kurtzman's royalties at EC cease and took his name off the credits of all Mad reprints. Still, many fans consider Kurtzman's years at Mad the magazine's golden period and argue that it never was quite as good again.

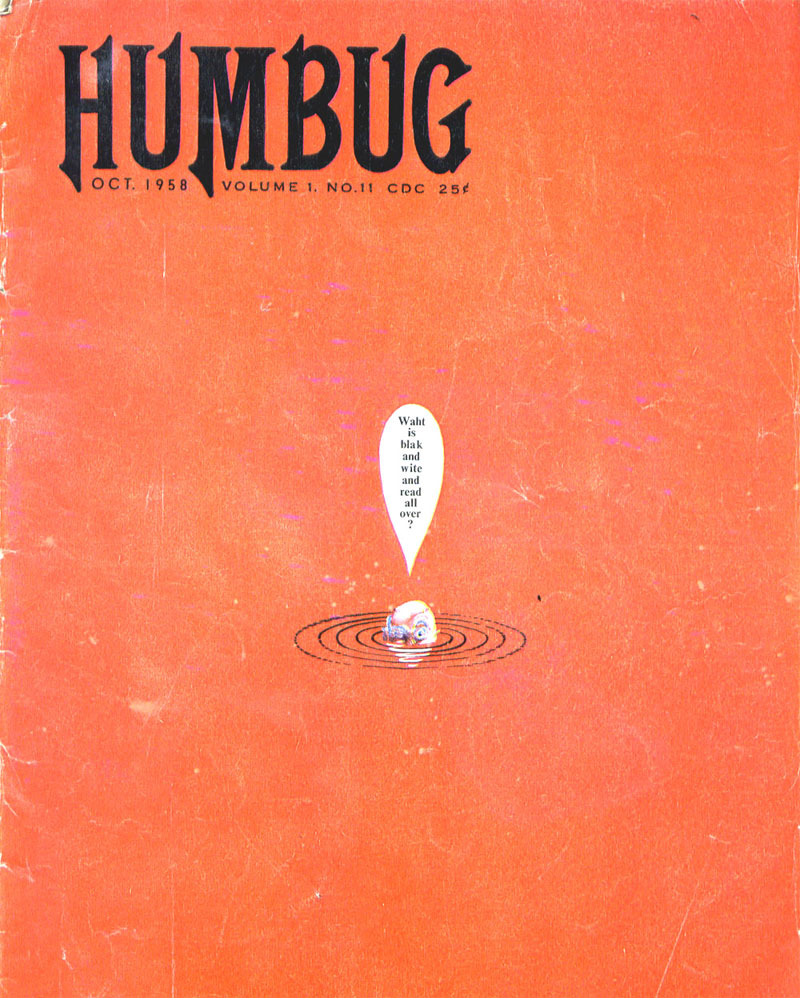

Cover illustrations for the first issue of Trump and the final issue of Humbug, by Harvey Kurtzman.

Trump

A huge fan of Harvey Kurtzman, Jack Davis and Wallace Wood, Playboy's chief editor Hugh Hefner offered the cartoonists an exclusive contract to publish in Playboy and/or create a new satirical comic magazine aimed at more mature readers. Kurtzman liked the offer, not only because the pay was better, but because Hefner was more open to his ideas than Gaines. In January 1957, the first issue of this new magazine, Trump, rolled from the presses. Just like Mad, it featured satirical comics, though the format was more luxurious and put more emphasis on sex jokes. Several Mad cartoonists were on board, among them Jack Davis, Will Elder, Al Jaffee and another E.C. Comics regular, Russ Heath. Only Wallace Wood eventually decided to remain loyal to Mad, since he didn't want to work exclusively for Trump. Among the newer names were R.O. Blechman, Ed Fisher, Irving Geis, Roger Price, Arnold Roth and writers like Max Shulman (famous for 'Dobie Gillis'), Doodles Weaver (a member of Spike Jones' band) and future comedy film director Mel Brooks.

While Trump sold well, Kurtzman far exceeded the budget Hefner had given him. Coincidentally, this happened when Playboy's major distributor, American News, faced bankruptcy. In order to keep out of debts, Hefner tightened his belt. He took himself off salary, gave his senior executives pay cuts and placed a quarter of Playboy's stock as collateral so he could loan some money. To his own regret he had to axe off Trump as well. He personally went to Kurtzman to tell him the bad news. To make matters worse, Kurtzman's wife had just given birth to their third child, Elizabeth. Kurtzman was devastated, since he felt Trump was the closest he ever got to making "the perfect humor magazine." Years later, Al Jaffee heard from Playboy's chief financial officer Bob Preuss that Hefner was also concerned that Kurtzman would never be able to make his deadlines. Either way, the final issue of Trump came out in March 1957. However, Hefner let Kurtzman advertise his next comic magazine Humbug in a lengthy nine-page article of that year's December issue of Playboy.

Humbug

Humbug was rushed out in the same year as Trump's demise. Published by Humbug, Inc., the first issue appeared in August 1957. Just like Mad, Humbug had a mascot, Seymour Mednick, whose name was borrowed from a real-life album cover designer. Humbug had the same satirical tone as Mad and Trump, but with a smaller budget and magazine size. Another notable difference was the more political satire. Most of the editorial board and contributing writers and cartoonists were the same as in Trump, with a few newcomers such as Ira Wallach and Larry Siegel. Humbug lasted longer than its predecessor, but because of its small size, it hardly stood out among all the larger-sized magazines. The 11th issue (October 1958) increased both its size and page numbers, but unfortunately not its sales. After Humbug's discontinuation, all of Kurtzman's artists returned to their old stable in Mad, which had managed to remain popular in the newsstands.

'The Organization Man in the Gray Flannel Executive Suit' (From: Jungle Book).

Jungle Book

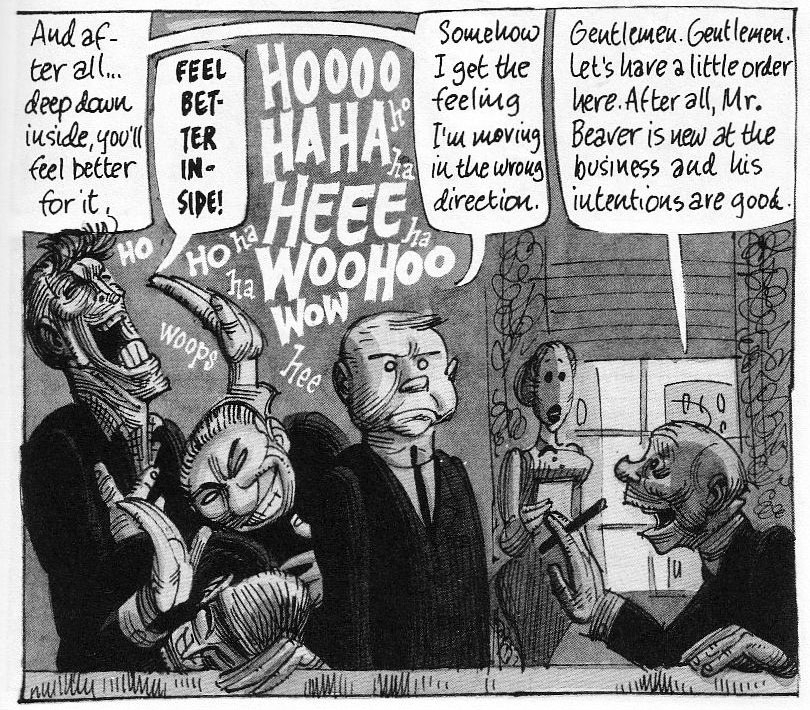

Undaunted after the demise of his previous magazines Trump and Humbug, Kurtzman created a satirical graphic novel named 'Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book' (Ballantine Books, September 1959). It was the first mass-market paperback of original comics put out by a publishing company. The comic book aimed exclusively at adults. Its satire was more pointed and Kurtzman toyed freely with lay-out, speech balloons, panels, graphic style, lettering and narratives. None of his other projects went so far in its graphic experimentation. 'Jungle Book', which had nothing to do with Rudyard Kipling's classic novel, had four chapters, all written and drawn by Kurtzman. 'Thelonious Violence, Like Private Eye' is a loose parody of the spy series 'Peter Gunn', though it targets more general spy fiction clichés. 'The Organization Man in the Gray Flannel Executive Suit' follows an idealist young editor, Goodman Beaver, who is corrupted by the publishing industry. The story was an obvious outlet for Kurtzman's own frustrations and experiences in that world. Certain characters in the story were archetypes for publishers he personally encountered, including Hefner. With 'Compulsion on the Range', Kurtzman satirized the more psychological westerns that came in vogue during the decade. It involved a psychiatrist trying to understand a cowboy marshall in his intentions to shoot down a certain outlaw. Finally, 'Decadence Degenerated' was a murder mystery set in the U.S. South, satirizing mob mentality and anti-intellectualism.

Like most innovative works, Kurtzman's 'Jungle Book' was ahead of its time. It didn't sell well and so no sequels came about. Still it had a strong impact on many cartoonists, who were inspired by its bold experiments. Many praise it as one of the earliest graphic novels. In 1986, 'Jungle Book' was republished by Kitchen Sink Press, with a foreword by Art Spiegelman. In 2014, Dark Horse Comics reprinted it again, adding an extra foreword by Gilbert Shelton and a double interview with Robert Crumb and Peter Poplaski about this landmark book.

'The Grasshopper and the Ant'.

One-shot comics for mainstream magazines

In 1960, Kurtzman created two parodies of classic children's stories. 'Pinocchio Retold' appeared in February 1960 in Pageant, while 'The Grasshopper and the Ant' was published in May of that same year in Esquire magazine. Both comics reimagine the characters as beatniks who question society, with Kurtzman parodying the typical language of their subculture. With 'Grasshopper', he got the opportunity to publish in color and took full advantage of it to represent the changing of the seasons. His attempt at creating a gag-a-day comic with Elliott Caplin, 'Kermit the Hermit', failed to find a publisher. To survive, Kurtzman wrote freelance articles for Esquire, Madison Avenue, Pageant, Playboy, the Saturday Evening Post and TV Guide.

Help!

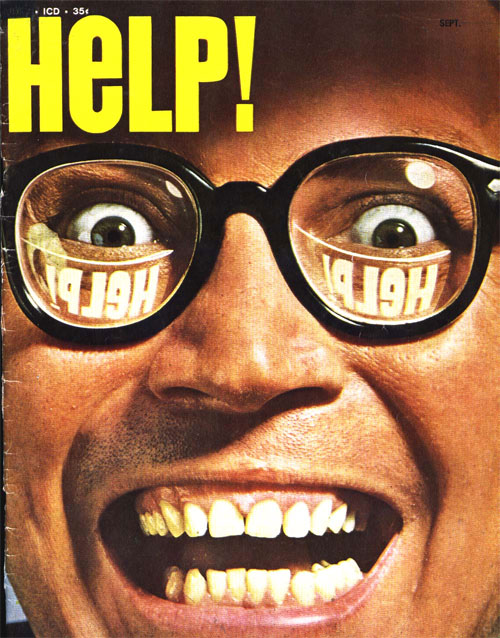

The longest-running post-Mad magazine edited by Harvey Kurtzman was Help! (August 1960- September 1965), brought out by Warren Publishing. It was also the cheapest. Most content were photographs and old illustrations, only with ironic captions and speech balloons added to them. This technique was later reused by other cartoonists as well. Help! also had a lot of photo comics, again easier to make than draw entire panels. Most of the actors in these so-called "fumetti" were staff members, friends and relatives. Some even celebrities like the comedians Jackie Gleason, Jerry Lewis and Mort Sahl and people who became more famous later on, like John Cleese and Woody Allen. The staff member in charge of recruiting these people was a still unknown Gloria Steinem - the future feminist icon. Help! presented many writers and cartoonists who later became celebrities, such as Paul Coker, Jean Bosc, Robert Crumb (whose 'Fritz the Cat' debuted here), Jay Lynch, Terry Gilliam, Rand Holmes, Spain Rodriguez, Skip Williamson, Jay Lynch (his 'Nard 'n' Pat' debuted here), Shel Silverstein and Gilbert Shelton (whose 'Wonder Warthog' debuted in its pages). Mad cartoonists like Jack Davis, sci-fi novelists like Ray Bradbury and Robert Sheckley also livened up the pages, as did reprints of old Punch cartoons and classic comics by H.M. Bateman, Winsor McCay, Milton Caniff, Bud Fisher, Heinrich Kley, Charles Dana Gibson, Thomas Nast, T.S. Sullivant and Caran d'Ache. Help! continued until September 1965, when its scream was silenced for good.

Covers for the September 1961 and September 1965 issues of Help!.

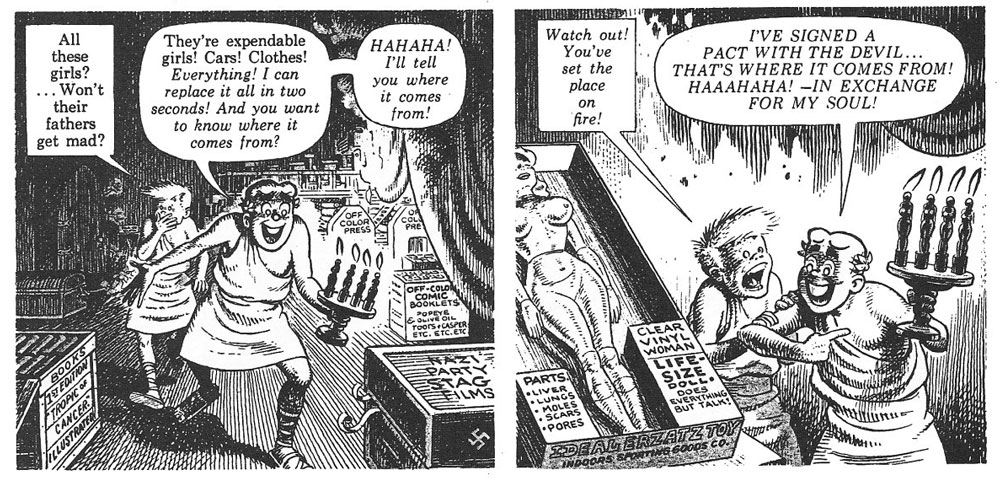

Goodman Beaver

Kurtzman's best known feature in Help! was Goodman Beaver, the naïve everyman he reused from his prior graphic novel 'Jungle Book'. From the 10th issue of Help! (May 1961) on, Beaver was featured in many satirical comics, illustrated by Will Elder. The young idealist typically finds himself in an odd location, asking questions about the madness surrounding him. In one episode he goes to Africa, where he confronts Tarzan with his supposed white colonial attitudes towards the natives. In 'Goodman, Underwater' (May 1962), Goodman meets a Don Quixotesque underwater crimefighter who fights invisible enemies. The entire story is done in the style of Gustave Doré's illustrations of Cervantes' famous novel. Other episodes brought Goodman in contact with Marlon Brando and a disillusioned Superman. In 'Goodman Goes Playboy' (issue #13, February 1962), the teenager meets Archie from Archie Comics who has now succumbed to the Playboy style. Archie and his friends turn out to have signed a pact with "the Devil", AKA Hugh Hefner. As many follow their example, Goodman wonders whether he "should leave to find a place where the dark forces aren't closing in... where honor is still sacred and where virtue triumphs?" But he quickly changes his mind: "Maybe I should sign up."

While Hefner himself enjoyed the parody, Kurtzman was sued by Archie Comics publisher John Goldwater. The case was settled out of court, with Help! running an apology in their next issue and paying 1,000 dollars in damage. Within a year, 'Goodman goes Playboy' was reprinted in Executive Comic Book, though Elder took the precaution of modifying the artwork. Archie Comics nevertheless sued again and in an out-of-court settlement received the copyright to the story, ensuring it could never be reprinted in its entirety. In August-September 2004 it was reprinted in the 262th issue of The Comics Journal, since it already entered public domain as Archie Comics had forgotten to renew its copyright over the strip.

'Goodman Goes Playboy' (artwork by Will Elder).

Little Annie Fanny

The irony about 'Goodman Goes Playboy' was that Kurtzman and Will Elder also signed up with Playboy. After Trump folded, editor Hugh Hefner still wanted to help the cartoonists out. He asked them to create a monthly comic strip in the style of 'Goodman Beaver'. Kurtzman took the same concept, but made the protagonist a big-breasted young woman, to appeal more to the magazine's readers. Starting October 1962, 'Little Annie Fanny' appeared on the final pages of each issue of Playboy magazine. Her name is a pun on the English word for a women's behind ("fanny"), while the title, logo and various side characters nod to Harold Gray's classic comic series 'Little Orphan Annie'. Fanny is often seen in the presence of her boyfriend/protector Sugardaddy Bigbucks, his assistant The Wasp and bodyguard Punchjab. Her mother Ruthie and best friend Wanda Homefree are also recurring characters. Just like Goodman Beaver, Fanny isn't terribly bright. The dumb blonde often finds herself in situations beyond her comprehension, which typically lead to her being stripped naked. But even then, she is utterly oblivious how many horny men (and occasionally women) want to lure at her. Kurtzman and Elder were directly inspired by a similar comic about a sexy girl with frequent wardrobe malfunctions, Norman Pett's 'Jane'.

'Little Annie Fanny' was the first comic strip feature in Playboy. Just like the magazine's single-panel erotic cartoons, it appeared in soft colors. Hefner paid double to render it in the same expensive four-color process printing. At his insistence, each panel was fully painted in oil, tempera and watercolor but without ink, which added to its gentle and lavish look. Since it was such a time-consuming job, Elder was often assisted by Russ Heath and Frank Frazetta, while other cartoonists like Jack Davis, Arnold Roth, Paul Coker, Larry Siegel, Bill Stout and Al Jaffee occasionally helped out to reach the deadlines. Despite its naughty comedy, Kurtzman's familiar satirical hallmarks were also present. Fanny and her friends often encounter real-life politicians and activists (Khomeini, Ralph Nader, Jim Bakker), novelists (J.D. Salinger, Philip Roth), Hollywood actors (Marlon Brando, Arnold Schwarzenegger), TV hosts (Howard Cosell), sports figures (Bobby Fischer) and pop stars (Elvis Presley, The Beatles, Alice Cooper). Throughout the decades, the feature satirized all kinds of trends and social changes, from advertisements, hippies, feminists and streaking (naturally!) to disco and personal computers. Certain episodes parodied popular TV shows (Jim Henson's The Muppets, 'The Love Boat') and movies (James Bond, Indiana Jones, E.T.).

'Little Annie Fanny', by Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder. With images from George Herriman's 'Krazy Kat' on the wall.

For 26 years, 'Little Annie Fanny' was a mainstay in Playboy's pages, and provided Kurtzman and Elder with a steady and royal income. The feature was so popular that rival nude magazine Penthouse ran a similar comic strip: Frederic Mulally and Ron Embleton's 'Oh, Wicked Wanda' (1969), though with a lower budget and different tone. Hustler's answer to both comics was James McQuade's 'Honey Hooker'. In Belgium, Yves Duval and Dino Attanasio's 'Candida' (1968), and in Spain Blas Gallego's 'Dolly' were obviously inspired by Fanny.

Nevertheless, 'Little Annie Fanny' has been a highly polarizing comic strip among Kurtzman fans. Some rank it among his best satires, others consider it too pornographic, sexist and formulaic. After all, Fanny's wardrobe had to malfunction every episode. The artists didn't even have total creative control over the end product either. Hefner checked every script and lay-out personally. He would veto certain elements, explain why they didn't fit in his magazine and even suggested improvements. To Kurtzman this was all very demoralizing and humiliating. He was also aware that he was now working for the same kind of a major corporation he used to lampoon. Even worse, he was promoting cheap marketing techniques, namely soft porn. But the artist needed the money. All his other projects went nowhere and above all he had a family to support, including an autistic son whose treatment cost a lot of money. 'Little Annie Fanny' kept going until September 1988, when Kurtzman was shocked to learn that he didn't own the rights to the series. He discontinued the feature immediately. Dark Horse Comics collected all episodes in two volumes. In 1998, 'Little Annie Fanny' was revived in Playboy by Ray Lago and Bill Schorr.

Reappreciation of Kurtzman

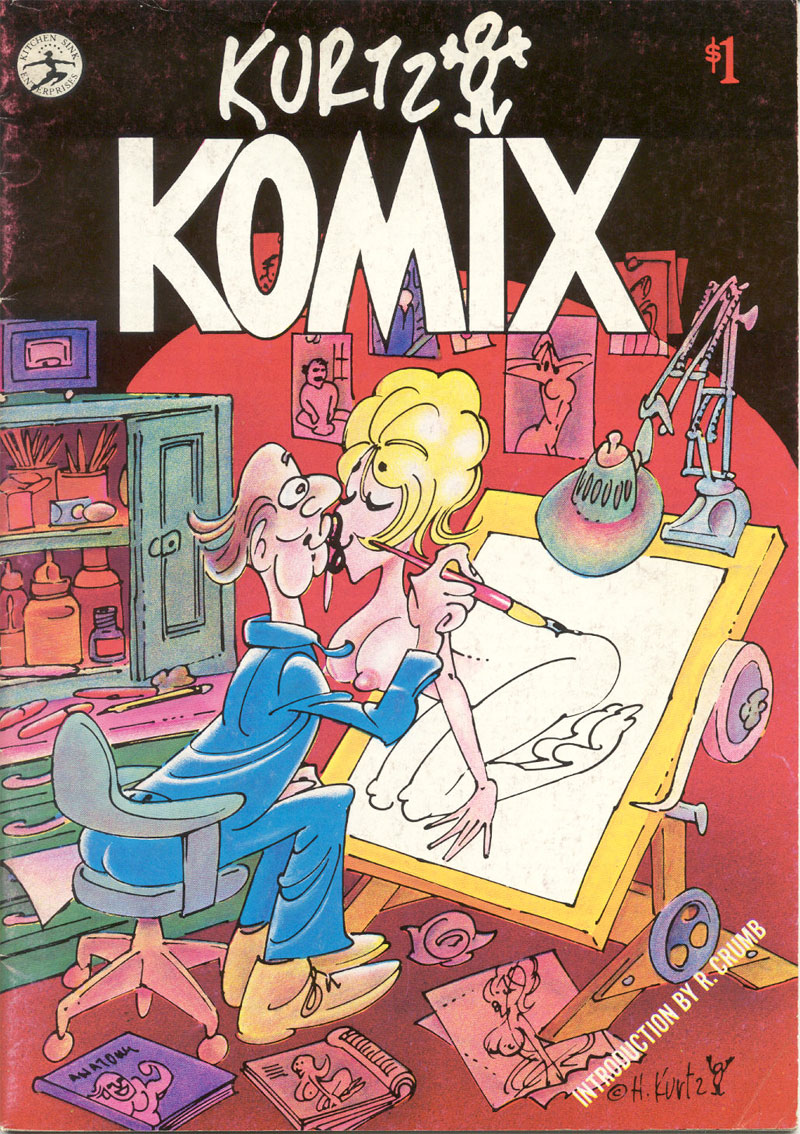

When the 1960s and 1970s rolled along, many children and teenagers who had read Kurtzman's work for EC and Mad Magazine were now adolescents questioning the core beliefs they had been raised with. Respect for the government, military, religious leaders, institutionalized racism, traditional role patterns, consumer society and mere acceptance of whatever the media feeds you was now replaced with a more anti-authoritarian stance. Kurtzman's work of a decade earlier was rediscovered and revaluated, also outside the USA. In October 1970, his work was reprinted in France in the magazine Charlie Mensuel, at the insistence of chief editor Georges Wolinski, who was a huge fan. In the same country, René Goscinny even asked Kurtzman to become the U.S. agent for his magazine Pilote, but he politely declined. He did the same with tempting offers from Marvel Comics and National Lampoon. Kitchen Sink Press published a compilation book, 'Kurtzman Komix' (1976), which had a foreword by Robert Crumb. They also reprinted 'Goodman Beaver' (1984), 'Hey Look' (1992) and 'Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book' (1988). Kurtzman made a graphic contribution to Marion Vidal's 'Monsieur Schulz et ses Peanuts' (Albin Michel, 1976), an essay about Charles M. Schulz's 'Peanuts' comic, illustrated with subversive parodies of the comic, that Schulz unsuccessfully tried to sue.

Animation career

Kurtzman co-wrote the script for the stop-motion animated film 'Mad Monster Party?' (1967). In 1973-1974, Kurtzman was contacted by Phil Kimmelman & Associates to create some animated shorts for Jim Henson's children's TV show 'Sesame Street'. Terrytoons veteran Dante Barbetta animated the segments, while Kurtzman's daughter Nellie was one of the voice actors. In 1973 he won "Best Script or Concept", "Best Direction" and "Best Humor Cartoon" at the Association of International Film Animation East. His short animated sketch 'Boat' also won in "Humor".

Educational career

Between 1973 and 1990, until health forced him into retirement, Kurtzman shared his skills and experience with the students at New York's School of Visual Arts, where he taught "Satirical Cartooning". For 15 years, he published Kar-Tünz, an anthology of student work which showcased the early work of later top comic artists. Kurtzman did this all in his own spare time, with support from advertisers, because the school didn't want to publish it. In 1988, Art Spiegelman held a guest lecture in the school about Kurtzman, someone not all students realized was a cartoonist legend.

Return to Mad

Between 1984 and 1989, Kurtzman returned to Mad magazine. He and Will Elder designed the covers of issues #259 (December 1985), #261 (March 1986) and #268 (January 1987). Most of his contributions during this period were advertisement parodies on the back cover, which appeared in color. However, he also illustrated comics and articles by Mad's regular writers, such as a parody of 'Wheel of Fortune' (issue #266, October 1986, with Dick DeBartolo and Will Elder). In the recurring features 'Mad's ... of the Year' and 'Mad Visits...', Kurtzman, Will Elder and Lou Silverstone tackled a banana republic dictator (issue #270, April 1987) and an organ transplant hospital (issue #272, July 1987). Another memorable entry was 'How to Pick Up Guys' (issue 265, September 1986), co-scripted with Arnie Kogen, and drawn by Elder, in which girls use suggestive pick-up lines thematically fitting to the location where they spot attractive men. Scripted by Tom Koch, Kurtzman drew 'Why Owning a VCR Is Better Than Going To The Movies' (issue #274, October 1987).

'Great Moments In Advertising - The Day AT&T Went Too Far' (Mad #263, June 1986), artwork by Kurtzman & Will Elder, satirizing TV commercials for AT&T telephone services and U.S. president Ronald Reagan and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

Recognition

Harvey Kurtzman received two Lifetime Achievement Awards, one in 1972 from the European Academy of Comic Book Art, and the other was an Inkpot Award in 1977. In 1989, he was inducted in the Will Eisner Hall of Fame.

Final years and death

In 1985, Kurtzman made his final attempt to launch another comic magazine, Nuts. Released in a paperback format by Bantam Books, it aimed at teenage readers, but barely lasted two issues. More successful was his annual charity auction, Association for Mentally Ill Children of Westchester, which is still held to this day. He was one of many cartoonists to be interviewed in the documentary 'Comic Book Confidential' (1988). Together with his former student Sarah Downs, he created the erotic gag comic 'Betsy's Buddies' (1980-1985) which ran in L'Écho des Savanes and, from June 1981 on, in Playboy. In 1990, the comic veteran published his last comic book, 'Harvey Kurtzman's Strange Adventures', which featured graphic contributions by several other artists, based on his lay-outs. He also tried to revive his military comic Two-Fisted Tales. In 1991, he and Michael Barrier wrote 'From Aargh! To Zap! Harvey Kurtzman's Visual History of the Comics' (Simon & Schuster, 1991), a historical overview of the comics medium.

In old age, Kurtzman was diagnosed with colon cancer, liver cancer and Parkinson's disease. He passed away in 1993. When reading his obituary in The New York Times, Art Spiegelman wrote a readers' complaint because it stated that Kurtzman had "helped" creating Mad Magazine, which to him was the same as claiming that Michelangelo "helped paint the Sistine Chapel, just because some Pope owned the ceiling". The mistake was corrected the next day. His most prominent co-worker Will Elder made an "in memoriam" cartoon in The New Yorker, while Adam Gopnik wrote a text.

In 2004, Spain Rodriguez made a funny "biographical" two-page comic strip, 'Harvey Kurtzman - Mad Man', published in Jewish Currents. In 2012, the Kurtzman and Al Feldstein estates filed to regain the copyrights to the EC Comics work of both cartoonists from the early 1950s. In 2017, comiXology released a previously unfinished comic book project by Kurtzman: an adaptation of Charles Dickens' 'A Christmas Carol'. Kurtzman had planned this adaptation in 1954 and had already signed up Jack Davis to work out the first two pages. However, no publisher at the time was interested and so Kurtzman shelved the project. More than half a century later, his script was finally released as a graphic novel: 'Harvey Kurtzman's Marley's Ghost'. Shannon Wheeler and publisher Josh O'Neil adapted his writings and sketched-out lay-out in a full-blown script, illustrated by Gideon Kendall.

Harvey Kurtzman and Wallace Wood spoofing all the Mad clones (Mad #17).

Legacy and influence

While Harvey Kurtzman is perhaps not a household name among general audiences, he left behind a large cultural footprint. The realism and pacifist messages of his EC war stories had a strong impact on series like Robert Kanigher and Joe Kubert's 'Sgt. Rock' (1959) and Archie Goodwin's 'Blazing Combat' (1965-1966). Many post-EC war comics have featured soldiers with more relatable fears and moral issues. At Mad, Kurtzman laid the foundations for their running gags, joke names, gross-out comedy, subversive satire, fake ads, eye-catching illustrations, border panels, funny background gags, twist endings and healthy disrespect for tired clichés. In the 1950s many copycat magazines of Mad came out: Bughouse, Cracked, Crazy, Eh!, Flip, Madhouse, Riot, Unsane, Wild and Whack. Between February-March 1954 and January 1956, even EC itself launched a sister magazine, called Panic!. The first 12 issues were written by Al Feldstein, the next six by Jack Mendelsohn. Kurtzman wasn't pleased with all these rip-offs, especially Panic!, since it felt like a conflict of interest. In issue #17 of Mad (November 1954), at the start of their 'Julius Caesar' parody, Kurtzman and Wood ridiculed all these Mad rip-offs on one page. Some of these magazines featured comics by artists who worked for Mad in the past, present or future. Most of them, except Cracked, barely lasted a few issues. For those interested in these publications, both John Benson's book 'The Sincerest Form of Parody' (Fantagraphics, 2015) and Ger Apeldoorn and Craig Yoe's 'Behaving Madly' (IDW, 2017) compile the best samples and descriptions of these forgotten magazines.

Mad also had an impact on adult humor magazines and not just in the comics genre. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, many U.S. college magazines modeled themselves after Mad. Their contributors were all first-generation Mad readers. Some managed to become proper magazines, but usually only for a while. In the United States, The Realist and National Lampoon had the most longevity. In Europe, Pilote, Hara-Kiri (since 1970 Charlie Hebdo), Private Eye, Humo, Fluide Glacial and Kréten also clearly borrowed from Mad. In Indonesia, the magazine Stop was also modeled after Mad. All copied the playful style, vicious satire and occasional fake ads. Erotic magazines like Playboy, Hustler, Penthouse and Screw had Mad-style parody comics and fake advertisements, but with more emphasis on graphic sex scenes. The underground comix movement of the mid-1960s and 1970s was also shaped by Kurtzman's editorship at Mad. The cover of Mad issue #16 (October 1954), drawn by Kurtzman, even coined the term, with a fake tabloid headline reading "the comics go underground". Many underground cartoonists were inspired by Kurtzman's depraved versions of familiar comics and ridicule of conformist society. They basically pushed it to more extreme levels. In a fitting tribute, the final issue of Jay Lynch's underground comix magazine Bijou Funnies (November 1973) was done entirely in the style of Kurtzman's Mad comics.

Crowded cartoon from the May 1952 issue of College Life.

Since generations of young Americans grew up with Mad, the influence of its parodies and self-reflexivity can also be felt in the films of Mel Brooks, Abrams and the Zucker Brothers ('Airplane', 'The Naked Gun') and several less inspired spoof movies. In a 2006 interview on the website Yahoo, David Zucker said: "Mad used to have two pages each issue of scenes they'd like to see in a Hollywood movie. We've just taken that attitude and added a Saturday Night Live approach to sketch comedy and created a story which we could then translate to the big screen." The spirit of Kurtzman and Mad also shaped live-action TV satire, such as 'Saturday Night Live', 'SCTV', 'The Tonight Show', 'Late Show with David Letterman', 'The Daily Show', 'The Colbert Report' and 'Late Night with John Oliver'. Various satirical animated TV series also continued the tradition, among them Matt Groening's 'The Simpsons', Tom Ruegger's 'Animaniacs', Everett Peck's 'Duckman', Bruce Timm and Paul Dini's 'Freakazoid', Trey Parker and Matt Stone's 'South Park', Seth MacFarlane's 'Family Guy' and Seth Green and Matthew Senreich's 'Robot Chicken'. Art Spiegelman and Woody Gelman's trading card Wacky Packages and Garbage Pail Kids were inspired by the fake ads in Mad.

In the United States, Harvey Kurtzman had a strong influence on Joel Beck, Nancy Beiman, Frank Cho, Daniel Clowes, Robert Crumb, Don Dohler, Drew Friedman, Mike Fontanelli, Terry Gilliam, Larry Gonick, Grass Green, Rick Griffin, Robert Grossman, Seitu Hayden, Al Jaffee, Batton Lash, Jay Lynch, John Blair Moore, Rick Parker, Bill Plympton, Mimi Pond, Gilbert Shelton, Art Spiegelman, Steve Stiles, Bill Stout, Genndy Tartakovsky, Vincent Waller, Wallace Wood, Skip Williamson, S. Clay Wilson and Bill Wray. Monte Beauchamp included Kurtzman in his book 'Masterful Marks: Cartoonists Who Changed The World' (Simon & Schuster, 2014), where the cartoonist's life story was adapted in comic strip form by Peter Kuper.

In Canada, Kurtzman has followers among John Kricfalusi and Bernie Mireault. In Europe, numerous humorous comic artists have cited Kurtzman as an inspiration. In the United Kingdom, he is admired by Alan Moore. Dutch followers are Hanco Kolk, Martin Lodewijk and Typex. Kolk based the soft-colored panels of his comic strip 'S1ngle' (co-created with Peter de Wit) on the visual style of 'Little Annie Fanny'. In France, René Goscinny, Marcel Gotlib, Nikita Mandryka, Jean-Claude Mézières and Wolinski admired Kurtzman, while in Belgium he influenced André Franquin, Willy Linthout and Morris. In Asia, Kurtzman inspired Japanese artists Toyoo Ashida and Monkey Punch. In South Africa, he influenced Zapiro.

Since 1988, Kurtzman's name lives on in the annual comics award, the Harvey Awards. He once summarized his vision to John Benson: "I don't regard myself as the satirist/philosopher of the Western world. All I'm really trying to do is to entertain people and remind them how the world really is."

Kurtzman's daughter, Meredith Kurtzman, was a contributor to the feminist underground comix magazine 'It Ain't Me, Babe' (1970).

Books about Harvey Kurtzman

For those interested in Harvey Kurtzman's career, his autobiography 'My Life as a Cartoonist' (co-written with Howard Zimmerman, Aladdin, 1988) is a good starting point. 'The Art of Harvey Kurtzman - The Mad Genius of Comics' (Abrams, 2009) by Denis Kitchen and Paul Buhle is another must-read. 'Simpsons' voice actor Harry Shearer provided the foreword. Another highly recommended book is 'Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Created Mad and Revolutionized Humor in America' (Fantagraphics Books, 2015) by Bill Schelly - with a foreword by Terry Gilliam - which won an Eisner Award for "Best Comics-Related Book". The Comics Journal also compiled all their interviews with Kurtzman in 'Harvey Kurtzman: TCJ Library, Volume 7' (2006).

Self-portrait from the back cover of 'Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book'.