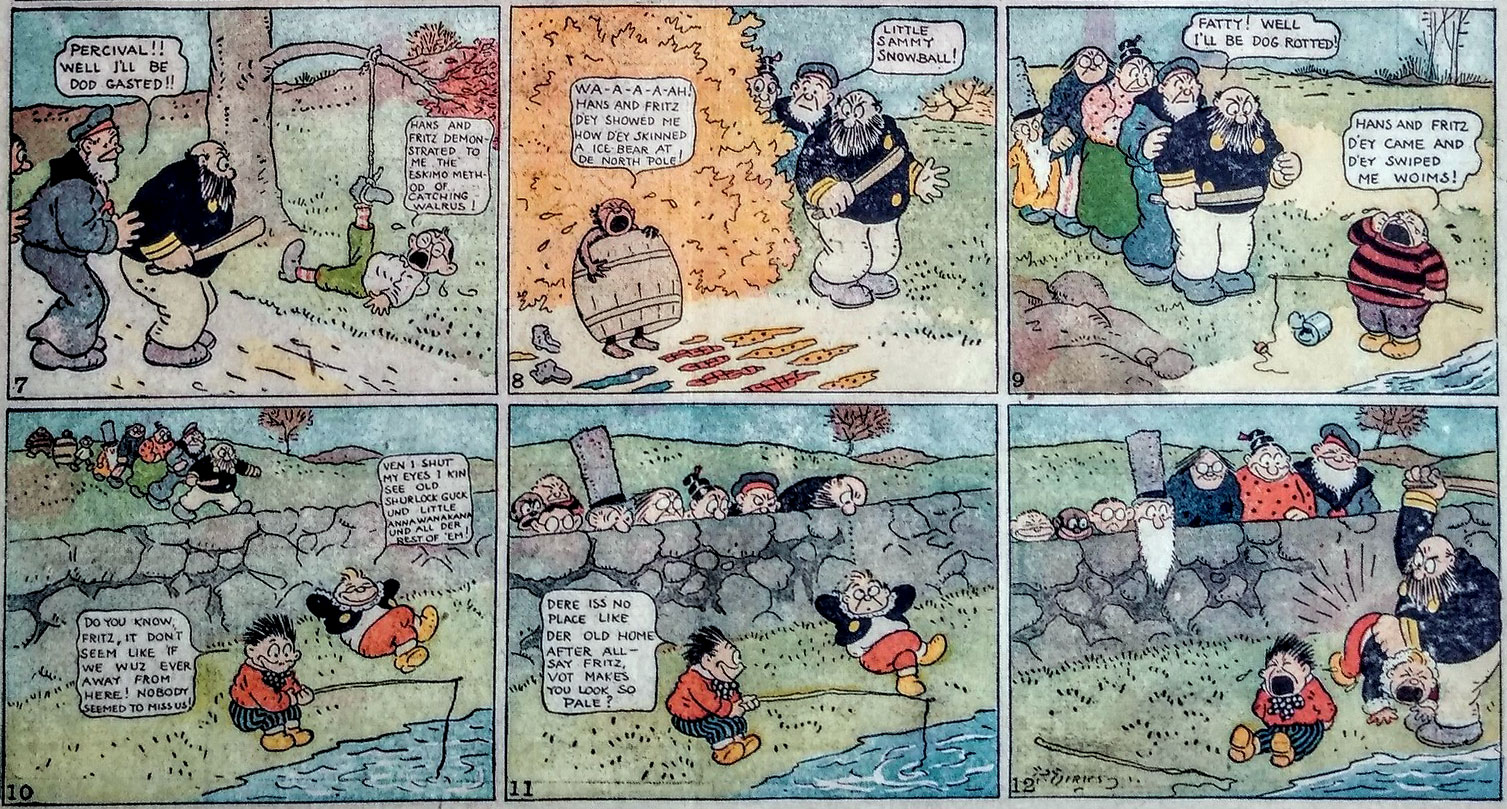

'The Katzenjammer Kids', 13 October 1907.

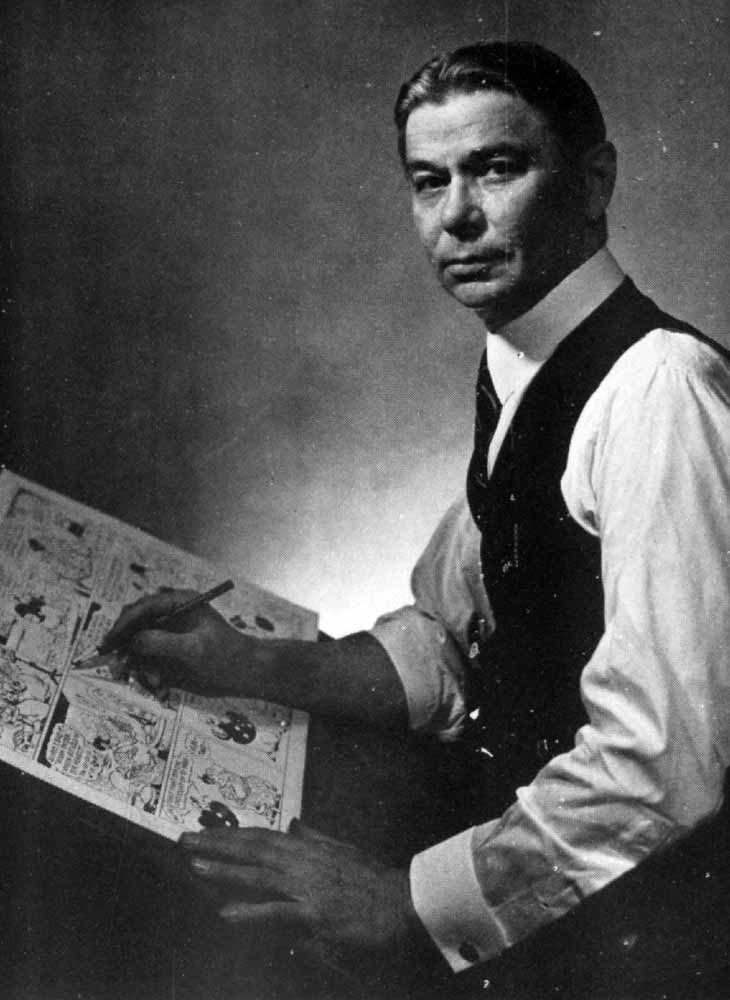

Rudolph Dirks was a late 19th-century, early 20th-century German-American newspaper comic artist, most famous for creating 'The Katzenjammer Kids' (1897-2006), the godfather of all newspaper gag comics. Published in the Sunday supplement of the New York Journal, the strip followed the prankster antics of two mischievous kids, Hans and Fritz, and their regular victims, Der Captain and Der Inspector. The comic was an instant hit, inspiring many merchandising items and the first ever film adaptation based on a comic strip. It also became the first U.S. comic that was translated all over the planet, finding a devoted worldwide fan base. Even when in 1913 Dirks lost the rights to his strip, he was able to continue it in another newspaper under a different title, 'The Captain and the Kids' (1914-1979). Together with Rodolphe Töpffer, Wilhelm Busch (on whose 'Max und Moritz' Hans and Fritz were directly based), the couple of Charles Henry Ross and Marie Duval and Richard F. Outcault, Dirks is among the most important and influential 19th-century comic pioneers. He is widely regarded as one of the key figures in the history and development of the modern comic strip. 'The Katzenjammer Kids' popularized gag comics, particularly the "trickster kid" subgenre. In its wake, countless artists from all over the world developed their own weekly one-page comic features in which one or more children pranks each other or adult authority figures. By reusing the same cast, Dirks built up familiarity, much like a family sitcom before the phenomenon existed. He also used his cast in longer serialized adventures, proving that his seemingly one-note gag characters could carry longer narratives. Produced almost non-stop for eleven decades, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' holds the record as the longest-running continuously serialized comic strip of all time and, despite being discontinued, the longest still in syndication today. It is also the only comic that has encompassed three successive centuries. Equally influential was Rudolph Dirks' graphic style. To keep up with his deadlines, he settled on simple drawings, with big-eyed, bulbous-nosed characters with large feet, nowadays known as the "big foot comics" style. The artist also made his dialogues just as important as the imagery. His characters speak in a funny mixture between English and German, a gimmick also copied by other humorous comic artists. While he didn't invent speech balloons or clearly defined panels, Dirks did popularize the technique. He additionally pioneered many symbols and visual metaphors that remain staples of comics to this day. From this perspective, Rudolph Dirks may be the most "complete" contender for the title "first modern comic artist."

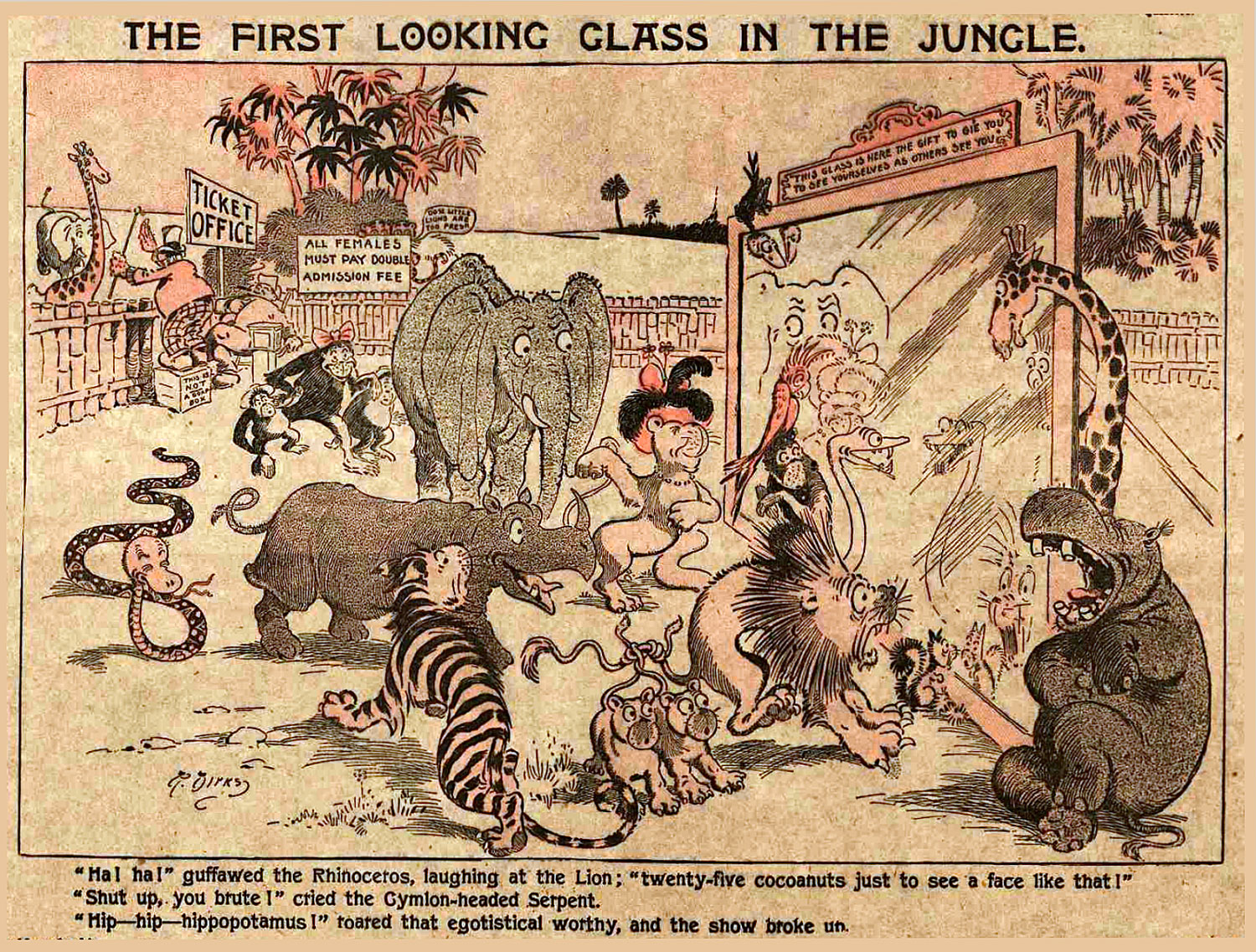

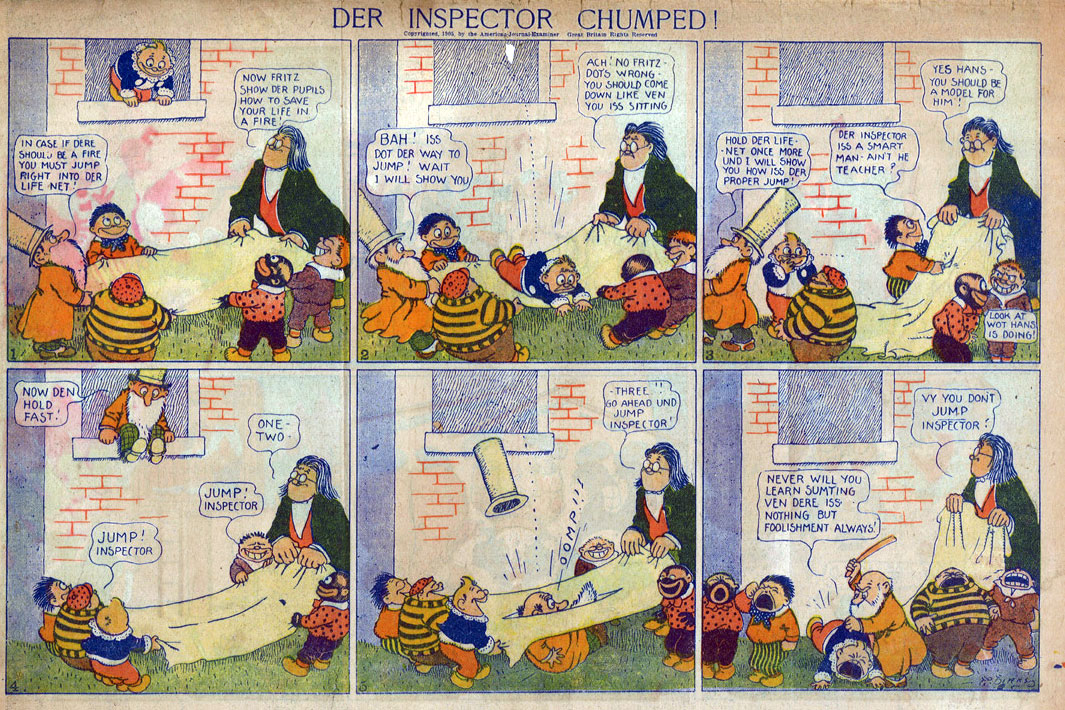

Gag cartoon published in the New York Journal on 27 November 1898.

Early life and career

Rudolph Dirks was born in 1877 in Heide, a town in the north of Germany. His father was a carpenter and woodcarver, who in 1884 emigrated to the United States, where the family first moved to Duluth, Minnesota, then settled in Chicago, Illinois. Rudolph's younger brother Gustav later became a notable comic creator in his own right. Originally, Rudolph was expected to follow in his father's footsteps, but after one week of practice in his father's workshop, he almost cut off his hand. He was far more interested in becoming an illustrator. His father had brought copies of the German humor weeklies Münchener Bilderbogen and Fliegende Blätter to the household, which Rudolph and Gus devoured. Among Dirks' main graphic influences were Arthur Burdett Frost, Karl Pommerhanz and especially Wilhelm Busch's classic picture story 'Max und Moritz'. In 1895, both Rudolph and Gus Dirks sold their first cartoons to the family magazine The Cricket. In the following year, Rudolph moved to New York City, followed a year later by his brother Gus. In "the city that never sleeps", both brothers made drawings for humor weeklies like Judge, Life and Puck. Besides livening up magazine articles with his cartoons and illustrations, Rudolph also designed covers for thriller books released by the publishing company Street & Smith. In New York City, Rudolph Dirks was quickly employed by The New York Journal, a paper owned by newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst. Among his early work for the paper were contributions to the humor page 'The Kaleidoscope'. Between December 1897 and at least until August 1900, he also drew a strip called 'In The Jungle'.

First appearance of the Katzenjammer Kids on 12 December 1897.

The Katzenjammer Kids: early years

While Dirks worked for The New York Journal, the paper was already well-known for its daily comic supplement, The American Humorist. Owner William Randolph Hearst was in fierce competition with Joseph Pulitzer's The New York World newspaper, which also offered daily comic series. In the period 1895-1898, Pulitzer's World had a huge hit with Richard F. Outcault's aggressively merchandised gag comic 'The Yellow Kid'. To counter the success, Rudolph Dirks was approached by his New York Journal editor, Rudolph Block, to also create a gag feature, preferably "something with children". Both Dirks and Block were of German descent and familiar with Wilhelm Busch's humorous bestseller picture story 'Max und Moritz' (1866-1867), a series about two boys who enjoy playing tricks on adults. In English translation, their antics had already appeared in The New York Journal.

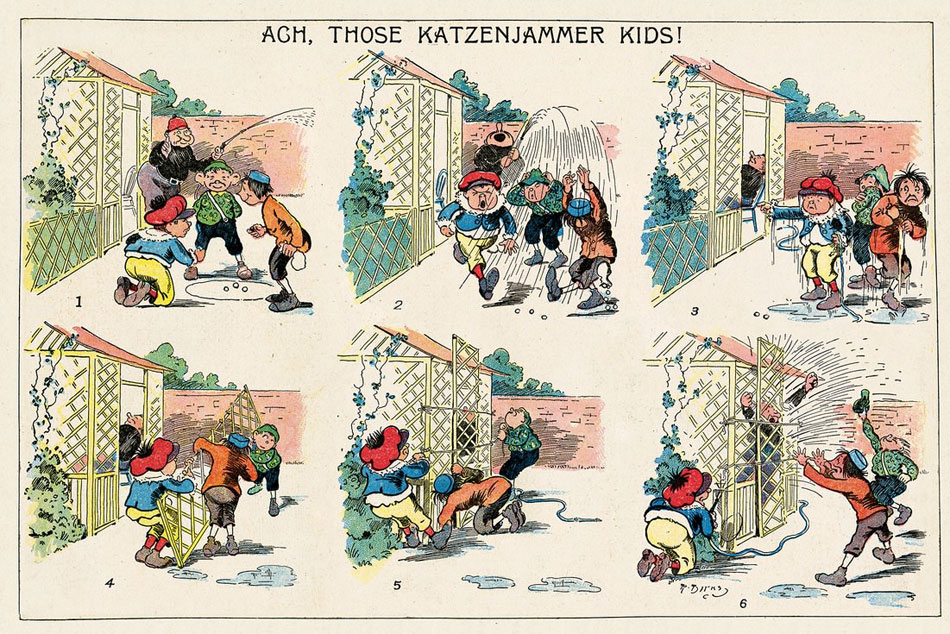

For his own comic, Dirks basically took Busch's duo, slightly redesigned them and gave them different names. The black-haired boy Max became Hans, though with a more spiky haircut. The blonde Moritz, whose hair has a cowlick, changed into Fritz. On 12 December 1897, their first gag page appeared in The New York Journal's Sunday supplement The American Humorist, the comic supplement of The New York Journal. In this debut episode, there are actually three children, Hans, Fritz and a dumbo-eared boy named Kurt. However, after only one gag, Dirks decided that two protagonists were more than enough and he dropped Kurt. Some of the early episodes were titled 'Hans and Fritz', with the caption "Ach, those Katzenjammer Kids" bemoaning their behavior. Eventually, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' (sometimes with a "Der" instead of "The" to highlight the "Germanness") became the definitive title. The German word "katzenjammer" (suggested by Block) literally translates to "screaming cats", although the word is generally used for a "hangover". Again, Dirks may have picked it up from Wilhelm Busch, who in issue #1174 of Der Fliegende Blätter (January 1868), drew an often reprinted picture story titled 'Der Katzenjammer am Neujahrsmorgen', about a man suffering from a hangover after a New Year's night. Although in Dirks' series, the term "katzenjammer" was originally implied to be an adjective (comparable to "those horrible kids"). In later gags, it was cemented as Hans, Fritz and their mother's last name.

Apart from the main characters, Dirks also took the basic setup from Busch's 'Max und Moritz'. Two boys pull off a trick, hurt or humiliate an adult and afterwards laugh at the results. Although 'The Katzenjammer Kids' is often cited as one of the most famous examples of plagiarism in comics, this reputation is not entirely deserved. Right from the start, and especially as 'The Katzenjammer Kids' continued, there were strong differences between Busch's picture story and Dirks' comic. For instance, 'Max und Moritz' is a text comic, with narration printed underneath the images. Like most 19th-century German children's literature, it is told in rhyme. 'The Katzenjammer Kids', on the other hand, started out as a pantomime comic, before eventually adapting speech balloons. Dirks rarely used narrative rhyme, though he also played with language by using a mixture of German and English. In 'Max und Moritz', the boys' parents are never seen or mentioned: they are only known to have an uncle. In 'The Katzenjammer Kids', Hans was originally a bit taller than Fritz, implying he is the oldest sibling. Gradually, both kids became shorter and chubbier, with less long limbs. Dirks would present them as identical twins, only distinguished by their haircut, hair color and clothing. He also gave them a mother, father, grandfather and uncle.

'The Katzenjammer Kids' of 7 August 1904.

The major difference between 'Max und Moritz' and 'The Katzenjammer Kids' is that Max and Moritz are basically nasty juvenile delinquents, indulging in downright vandalism, burglary, assault and theft. They are only punished after seven pranks, when a miller grinds them flat and ducks eat their remains. Busch concluded his tale with a moral, defending the boys' gruesome death as justice for their evilness. In early 'Katzenjammer Kids' gags, Hans and Fritz aren't particularly naughty. In their debut gag, they actually start out as victims of a mean-spirited adult, who sprays them wet with a hose. They soon give him a taste of his own medicine. In other early gags, Hans and Fritz merely find themselves in mayhem caused by youthful ignorance, without intending any harm. But Dirks soon established Hans and Fritz as malicious brats.

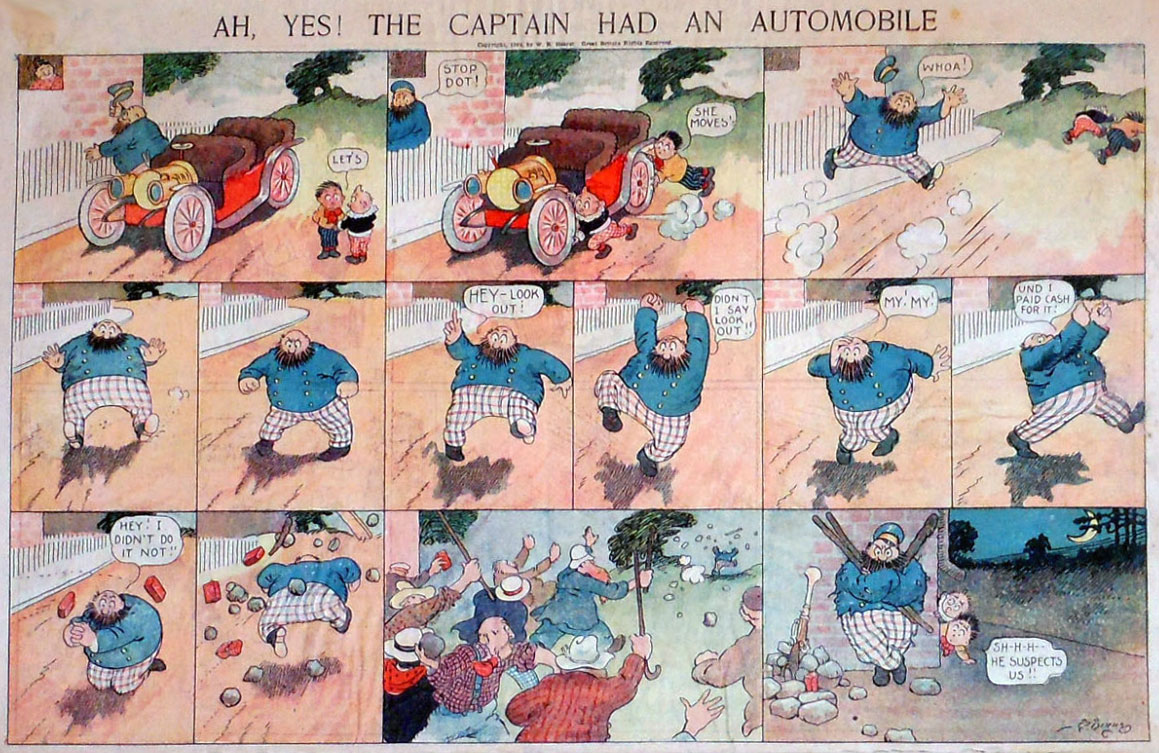

Delving deep into his inner child, Dirks came up with hundreds of amusing pranks. Much like Max and Moritz, Hans and Fritz don't even need a reason or provocation. They just go ahead and torment adults, small animals or other kids. Most of their "jokes" are on the level of typical boyish pranks. Others succumb into life-endangering vandalism. Hans and Fritz see no qualms in dropping boulders on submarines, pushing ladders away while someone is standing on them, or blowing up their house with gunpowder. Contrary to Busch, Dirks obviously wanted to keep his anti-heroes alive, so he went for a more traditional, albeit nowadays discouraged, punishment: spankings. At the end of many gags, Hans and Fritz are beaten, usually bent over an adult's knee. In some episodes, they are tied to a wooden rack and slammed with a stick. Other times, Dirks ends the episode with furious adults searching for Hans and Fritz. The boys' spankings not only mark one of the earliest examples of a running gag and trademark ending in a comic strip, but were also a fitting way to combat censors. Hans and Dirks' inevitable corporal punishment at least showed young readers the consequences of their paper heroes' bad behavior. And yet, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' was never preachy. The brats never take a moment to lecture their audience on what they have "learned". Quite the contrary: as true recidivists, they can't resist the temptation of playing yet another prank in the next episode. Dirks sometimes even let them get away without punishment.

Interestingly enough, Dirks and Hearst were also able to continue 'The Katzenjammer Kids' for decades without "punishment" from the copyright holders to Wilhelm Busch's creations. In the mid-1890s, 'Max und Moritz' ran in the German-language edition of Hearst's The New York Journal, where the 'Katzenjammer Kids' gags were originally presented as "new" Max und Moritz episodes. In the 1990s, comic scholar Alfredo Castelli uncovered that Hearst had taken a legitimate license on 'Max und Moritz'. Busch never saw a dime of it, since he had sold his rights to the German publisher Kaspar Braun long before 'Max und Moritz' became a hit. It seems unlikely that Busch was even aware of 'The Katzenjammer Kids'. Around the time the series became a hit in the USA, he was already old and in ill health. Official European translations of Dirks' comic only took off in 1908, the year of Busch's passing. Before that date, the few gags that ran in some local European magazines were presented as one-shots, and not as an actual series. Even worse, several were shamelessly plagiarized by local cartoonists, without crediting Dirks. Also, Dirks' comic evolved so quickly into something that barely resembled 'Max und Moritz' any longer, that its similarities wouldn't have been so obvious.

Introduction of "Die Mamma" in the second episode of 'The Katzenjammer Kids' (19 December 1897).

The Katzenjammer Kids: cast

Already in the second 'Katzenjammer Kids' episode, printed on 19 December 1897, the second main character made her debut in the series: Hans and Fritz's mother. They refer to her as "Die Mamma", though her actual name is Lena. Contrary to the boys, Die Mamma's physical design didn't change much over time. In her earliest appearance, she already had a long nose, bun haircut and large skirt with an apron. The only difference was that she was originally more slim and later grew more corpulent. Die Mamma is in utter denial over her sons' misbehavior. She enjoys baking cakes for her "liddle anchels", unaware that this only provides them with more ideas for mean-spirited shenanigans. Yet when she is targeted, she punishes them without mercy.

During the series' first five years, Hans and Fritz had a father, grandfather and a bearded uncle, Heinie, who is a sailor. But these characters were simply interchangeable targets for Hans and Fritz' schemes, without much personality. On 24 August 1902, Dirks removed the boys' father and grandfather, replacing them on 31 August with an obese, bald, black-bearded sailor. Everybody always refers to him as "Der Captain", although in an 18 November 1906 gag, he is revealed to be named Louie. Uncle Heinie remained part of the cast a little bit longer, but eventually had fewer and fewer appearances. Officially, Der Captain is a tenant, who lives with Die Mamma, Hans and Fritz. Nevertheless, many readers instinctively assume he is her husband and the boys' father. Either way, he does act as a surrogate parent, disciplining the boys and being their favorite irresistible target, whom they nickname "Der Walrus".

Der Inspector in 'The Katzenjammer Kids'.

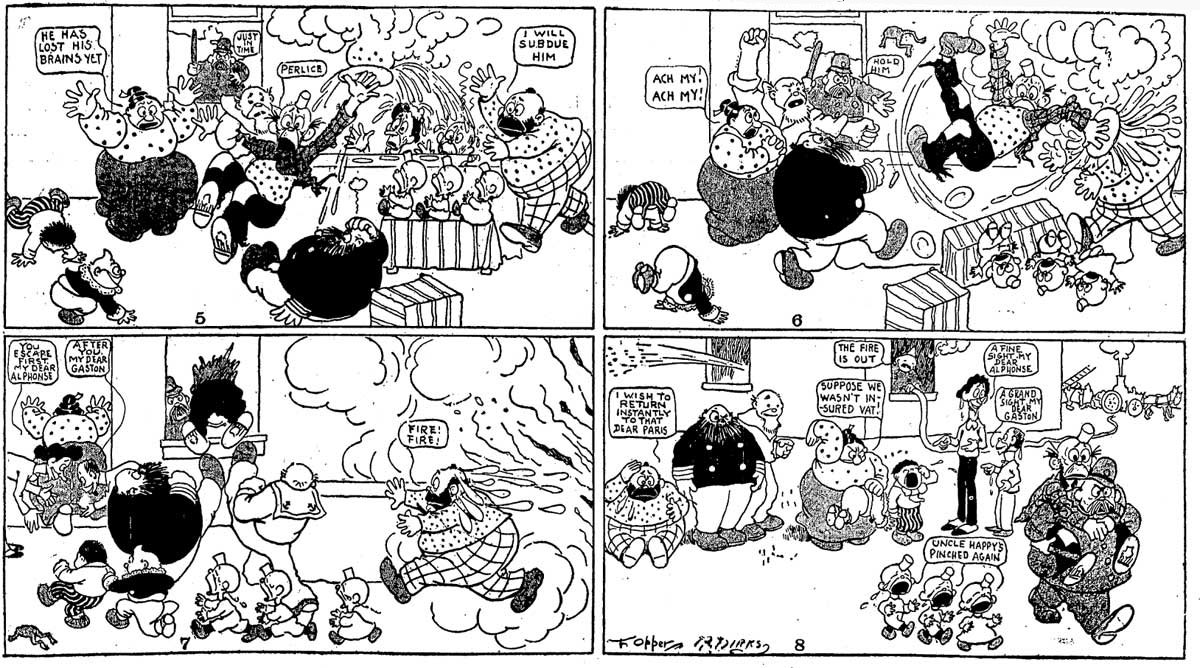

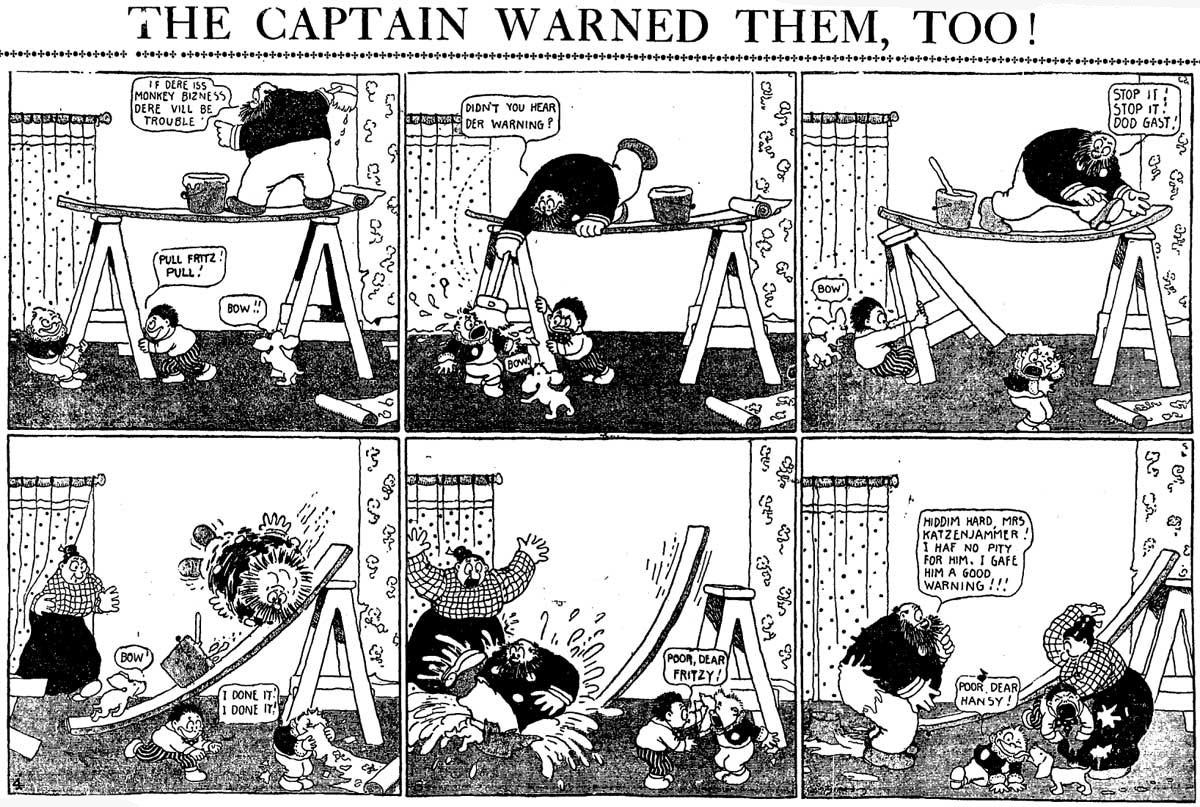

In early gags, Hans and Fritz were sometimes disciplined by a long-haired, bespectacled teacher, but he eventually made less frequent appearances. On 15 January 1905, a long-bearded truant officer in a high hat was sent on Hans and Fritz' tails: Der Inspector. His dedicated, but hopeless mission to catch Hans and Fritz skipping school and put them back behind their desks gave the series a new looming threat. The boys unsurprisingly see Der Inspector as their mortal enemy, nicknaming him "The Goat". Der Captain and Der Inspector are good friends. They often go fishing together, but most of their spare time is wasted trying to discipline the devious duo. During the 1900s and early 1910s, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' sometimes featured cameos by characters from other comic series that ran in William Randolph Hearst's The New York Journal, like Frederick Burr Opper's Happy Hooligan, Alphonse & Gaston and Carl Emil Schultze's Foxy Grandpa. Dirks' colleagues would also draw their respective characters for those "special" episodes, making them early examples of crossover comics.

23 November 1902 episode of the 'Katzenjammer Kids' with guest appearances from characters from Frederick Burr Opper's 'Happy Hooligan' strip.

By 1905, Hans and Fritz had enough side characters to torment constantly and, in retribution, be punished by. This neverending vicious circle often exhausts the adult characters, who frequently sigh in despair: "Mit dose kids, society is nix!" ("With those boys, society is doomed"), which became a catchphrase. Though, in reality they aren't model figures either. Particularly Der Captain and Der Inspector sometimes conspire against Hans and Fritz, Die Mamma or even each other, without any other reason than enjoying a mischievous trick of their own. As the years progressed, the comic moved beyond the one-sided "trick vs. contra-trick" formula that had personified 'The Katzenjammer Kids' since the beginning. The jokes became less anarchic and sadistic and more a playful game of wits between worthy opponents. Later Dirks also added ongoing adventure narratives, serialized with cliffhangers. In this new incarnation, the series had more variety. Some episodes didn't even feature pranks at all.

Germanized dialogues in 'The Katzenjammer Kids' of 8 March 1903.

The Katzenjammer Kids: language

A distinctive aspect of 'The Katzenjammer Kids' is the colorful language. Words are often spelled phonetically, to imply a stereotypical German accent, for instance: "brudder" ("brother") and "togedder" ("together"). The prefixes "Die", "Das" and "Der" are put in front of every noun, including the series title, 'Der Katzenjammer Kids'. The conjugation "is" is spelled as "iss" and "have" as "haf". Every "-w" transforms into a "-v" ("what" = "vot"), while a "-v" can become an "-f" ("every" = "effery"). If an "-s" is necessary, it will be spelled as "-sh" ("strange"= "shtrange"), while words starting with a "-j" is replaced with one starting with "-ch" ("just"= "chust"). Dirks mangled words with a "th" by giving them a "-d" ("that"="dot", "this" = "dis"). To round it all off, each "and" becomes "und", "with" is replaced by "mit" and "of" becomes "von". Apart from spelling and vocabulary, sentences also follow syntaxes influenced by German grammar ("In my school, d'ey came"). The Teutonic flavor is extra emphasized by recurring loan words. When characters express surprise, they shout "Himmel!" ("Heavens above!") or "Ach du Lieber!" ("Oh dear!"). If they're angry, they mutter "Donnerwetter". At first, only Hans, Fritz and their direct family spoke this funny mixture of German and English. Later, other characters also picked it up, regardless whether they had German roots or not.

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the United States had a global attraction to immigrants, making the country a veritable melting pot of nationalities. Ethnic comedy was therefore very popular in white Western entertainment. At the time, Germans were the largest immigrant group in the U.S., making their foreign accents widespread and recognizable. General readers of 'The Katzenjammer Kids' enjoyed this linguistic gimmick, even if it made the dialogue less easy to decipher. Most real-life German-Americans were also amused. The fact that Dirks was one of them undoubtedly helped. From a young age, he had heard everybody in his family and their neighborhood talk with this strong German accent and odd grammatical constructions. He merely transcribed it on paper. The Katzenjammers' "German English" remained a hallmark of the series for decades. However, when the gags ran in the German-language edition of The New York Journal, translators used standard German instead. Other foreign translations of 'The Katzenjammer Kids' didn't use the "German" linguistic gimmick either.

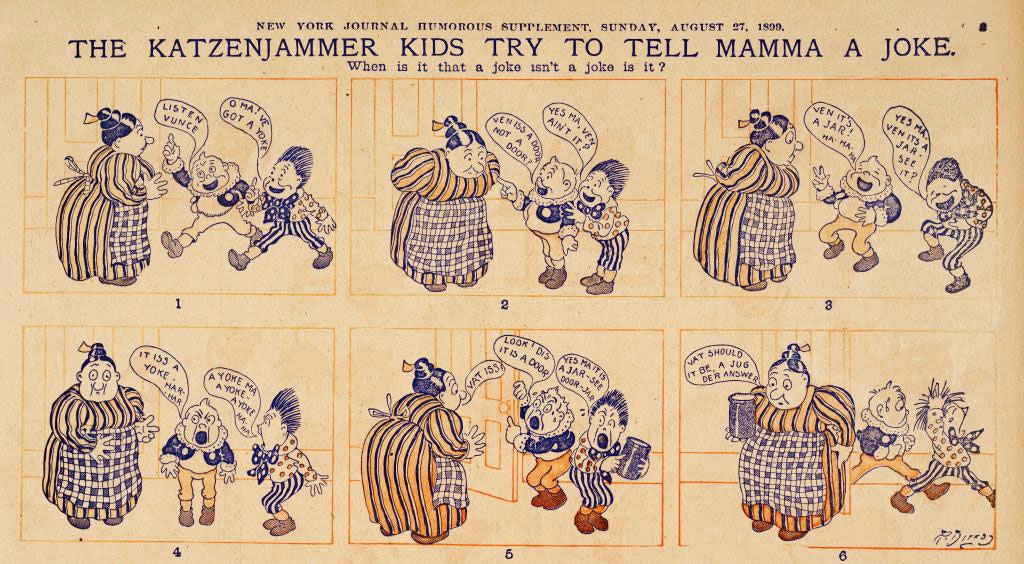

'The Katzenjammer Kids' strip of 27 August 1899, the first where speech balloons in the series are used in comic strip dialogue format.

Graphic and narrative innovations

Rudolph Dirks was in many ways a trendsetter. By introducing innovative graphic techniques, like clearly defined panels, movement lines and visual metaphors, his characters and their actions look more alive than many other early newspaper comics. Dirks first used a speech balloon in a one-panel 'Katzenjammer Kids' cartoon from 19 March 1899 and again in 'Katzenjammer Kids' cartoons and strips from 2 July, 6 August and 20 August of that year. Yet it didn't become a permanent fixture of the series until 27 August, when the kids tried to tell their mother a joke that she didn't understand. This specific gag is additionally notable because the speech balloons are used as a dialogue instead of a monologue. Comic historian Eike Exner discovered that, even then, Dirks kept switching between pantomime comics, balloon comics and text captions until around 1900, when the series transformed into purely a balloon comic. The usage of speech balloons brought readers more into the stories, since they were no longer forced to read blocks of text underneath the panels, as was common at the time.

Dirks also built up familiarity. At the time, most gag comics were one-shot jokes. If artists used recurring characters, it was typically one or two protagonists with little personality. For his comic, Dirks used several distinguished characters and a standard set-up. The comedy is derived from the interactions and contrasts between the cast members, offering more variety in plot possibilities. 'The Katzenjammer Kids' uses a very homely setting, with most gags taking place in and around the boys' home and involving their mother and (surrogate) father, Der Captain. This made his comic series more cozy and recognizable to average readers, who came to expect the familiar running gags and sympathized with their beloved, colorful characters. Soon, they looked forward to each episode, in anticipation of what Hans and Fritz were up to now. In a sense, Dirks pioneered the concept of a "family sitcom" before the term existed. He can even be regarded as the first known comic artist to create a series about a dysfunctional family.

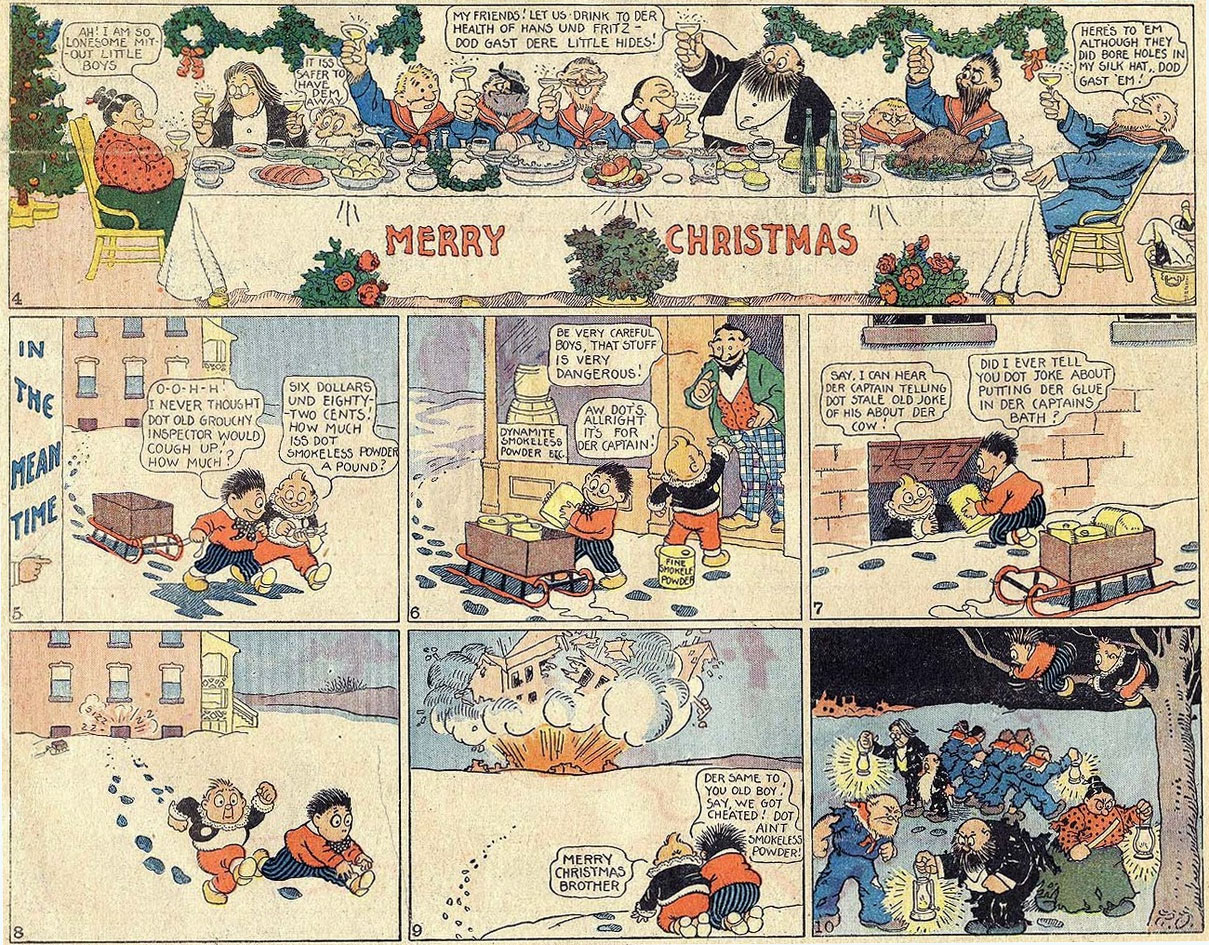

Children have always enjoyed stories about tricksters. They delight in fooling others, or getting even with them, whether at home, in school or in their neighborhood. From this perspective, The Katzenjammer Kids' pranks were very relatable. The same applied to their recurring spankings. Until well into the 20th century, children were still expected to be silent and obedient. Corporal punishment was considered a normal method to discipline them. Even though Hans and Fritz are often punished, it couldn't diminish young readers' thrill of seeing them skip school, fool adults, create mayhem and have a lot of fun in between. While 'The Katzenjammer Kids' was far from the only gag comic about kids playing pranks, it still had a more anarchic streak than its rivals. In a 1906 Christmas episode, Hans and Fritz aren't allowed to attend dinner because "they put sawdust in the mince pie". Out of revenge, they beg the adult visitors for nickels, lying that they want to buy a present for Der Captain. In reality, they use the cash to buy smokeless gunpowder and blow up their house. When the building explodes, the boys have no empathy, guilt or remorse. Their only objection is that the gunpowder wasn't "smokeless", making them regret wasting their money on it. 'The Katzenjammer Kids' fulfilled a deep human desire and childhood fantasy of rebelling against authority.

'Katzenjammer Kids' strip of 10 December 1905.

The Katzenjammer Kids: American and international appearances

During the majority of its record-long run, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' was a Sunday comic, with only a brief excursion as a daily comic in the post-Dirks period under the title 'The Katzies' (28 May 1917-1919). During the early years, the gags of Hans and Fritz were syndicated to American newspapers by the American-Journal Examiner (1904-1912) and the Star Company (1912-1919), after which the King Features Syndicate became the comic's permanent distributor. Starting in 1934, 'Katzenjammer Kids' comic book compilations were published by Saalfield Publishing, taken over by Dell Comics in 1939. 'The Katzenjammer Kids' were also widely spread abroad.

In the German-language edition of The New York Journal, aimed specifically at German immigrants who weren't fluent in English, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' enjoyed their first translations as early as 1898. Interestingly enough, they were referred to as Max und Moritz. 'The Katzenjammer Kids' was not the first American comic to be reprinted and translated in foreign magazines, but it was the first to actually become popular abroad. In the 4 May and 15 June 1899 editions of the French children's weekly Le Journal Pour Tous, a supplement of the Parisian paper Le Journal, two pantomime episodes of 'The Katzenjammer Kids' were printed as standalone gags instead of a series. European readers had to wait another decade before the comic was presented as an ongoing series. In 1908, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' were launched in Denmark under the title 'Ole og Peter' (later retitled to 'Knold og Tot'). Their antics were translated all over the globe. In French, they were originally serialized under the title 'Des Petits Chaperché', before, from 1938 on, appearing in Le Journal de Mickey, where they received their permanent new name 'Pim Pam Poum'. In The Netherlands, the series ran under three separate titles, 'De Jongens van Stavast', 'De Doerakkers' and later 'Kapitein Bulder en de Belhamels'. This latter title, 'De Belhamels', was also their name in Flemish children's magazines. The series also ran in Italian ('Bibì e Bibò'), Spanish ('Maldades de dos pilluelos' or 'Los Cebollitas'), Portuguese ('Sobrinhos do Capitão' or 'O Capitão e os Meninos'), Norwegian ('Knoll og Tott'), Swedish ('Knoll och Tott'), Finnish ('Kissalan pojat') and Russian ('Bim and Boom'). 'The Katzenjammer Kids' have been particularly popular in Norway. In 1911, they starred in the earliest comic books released on Norwegian soil. Christmas annuals are still published to this day. In 2001, the local artist Henrik Rehr received permission to redraw old episodes that couldn't be reprinted otherwise.

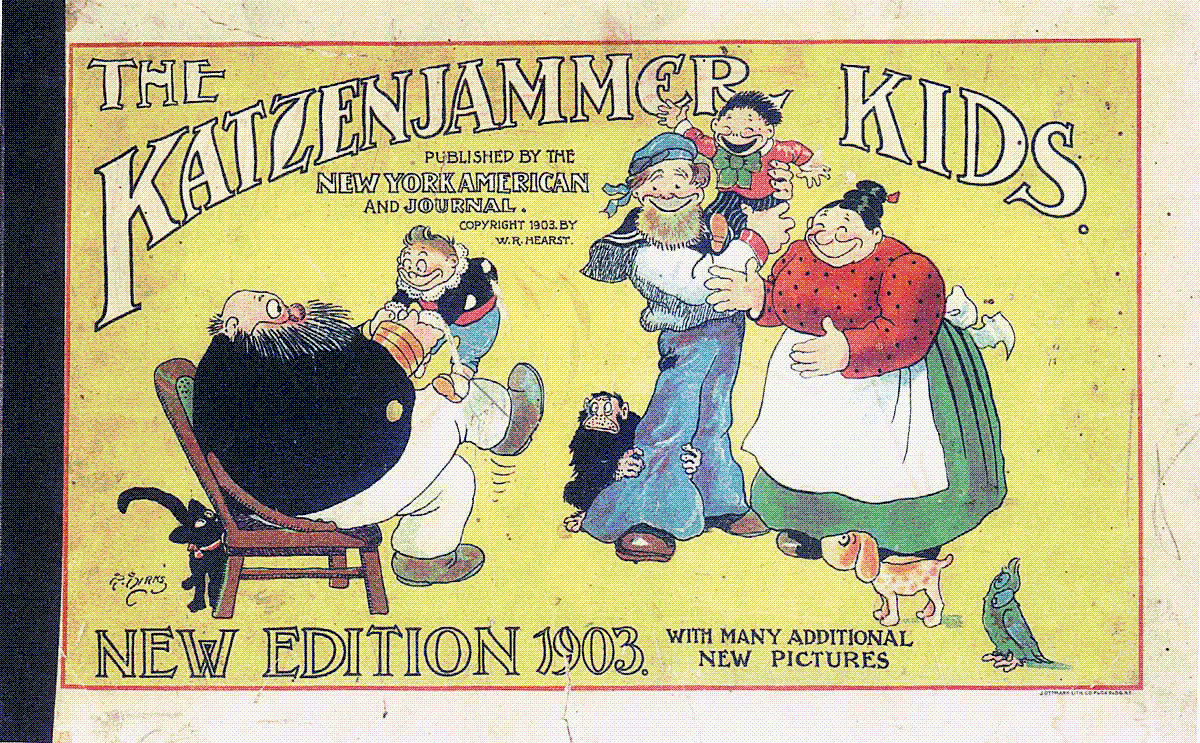

'The Katzenjammer Kids' compilation book in landscape format, 1903.

The Katzenjammer Kids: merchandise and adaptations

The characters spawned a truckload of merchandising, including dolls, masks, jigsaw puzzles and cereal boxes. As early as 1898, the Biograph Company produced a live-action silent slapstick film, 'The Katzenjammer Kids in School' (1898), followed by 'The Katzenjammer Kids in Love' (1900). This was the first film adaptation of a comic strip in history. In 1903, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' were adapted into a stage play. The show travelled the United States and Canada for several years. On 28 November 1929, Hans, Fritz, Die Mamma, Der Captain and Der Inspector became the first comic characters to appear on huge balloons carried around during the 6th edition of Macy's Thanksgiving Parade (and not Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer's Felix the Cat as several sources have mistakenly claimed). Their appearance actually kicked off the enduring tradition of featuring comic and cartoon characters as huge balloon animals during Macy's parade. During the first edition, held on 27 November 1924, there were already appearances by George Herriman's Krazy Kat and Bud Fisher's Mutt & Jeff, but then as actors appearing in costume, rather than balloons.

In 1915, William Randolph Hearst established his own film studio, the International Film Service (I.F.S.). One of its projects were animated shorts based on the most popular Hearst newspaper comics. Between December 1916 and August 1918, 37 silent, black-and-white animated cartoons based on 'The Katzenjammer Kids' were directed by Gregory LaCava. Still, like most cartoon adaptations of Hearst newspaper comics by the I.F.S., the animation was primitive and stuck too close to the source material. Characters literally used speech balloons to communicate, forcing all action to freeze during these scenes, so viewers could read the dialogue. The animated shorts disappointed fans of the original comics and failed to impress newcomers. By 1918, all production was discontinued. In the following decades, most of I.F.S.' cartoons were destroyed because Hearst feared they might have a negative effect on his comics if anybody reran them again.

In 1938, M.G.M. made a series of animated shorts based on Dirks' later 'The Captain and the Kids' strip, directed by Friz Freleng and William Hanna (of later Hanna-Barbera fame), but this version didn't catch on. In 1971, the Katzenjammer Kids were also featured in 'Archie's TV Funnies' (1971) and 'Fabulous Funnies' (1978-1979), produced by Filmation, while they also had guest appearances in Hal Seeger's TV special 'Popeye Meets the Man Who Hated Laughter' (1972).

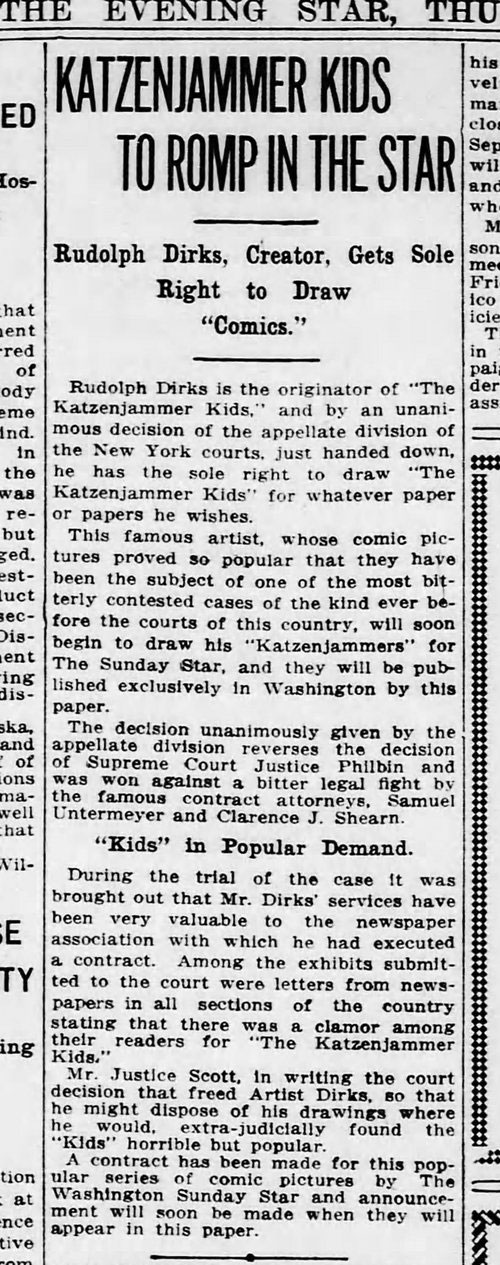

The end result of the court case was covered in the Evening Star of 28 May 1914.

Dirks-Hearst court case (1913-1914)

By 1912, Rudolph Dirks had drawn 'The Katzenjammer Kids' for 15 years non-stop, a couple of interludes aside. During the cartoonist's 1898 military service, his brother Gus Dirks filled in, and in 1910 an anonymous ghost artist drew several episodes. In the early 1910s, Dirks wanted to take a sabbatical and travel to Europe and focus on painting. Publisher William Randolph Hearst gave him no permission, but Dirks went anyway. However, Hearst had dealt with disobedient cartoonists before, like Richard F. Outcault, by simply firing and replacing them. As a result, Dirks' final 'Katzenjammer' gag appeared in print on 16 March 1913. Following his discharge, Dirks decided to sue the powerful newspaper mogul, forcing 'The Katzenjammer Kids' to rely on reprints for more than a year. A long and bitter court case ensued, which Hearst initially won. The judge ruled that Hearst, as owner of The New York Journal, also owned the rights to the comic strip's title. Dirks went on appeal and in late May 1914, the jury ruled partially in his favor. While Hearst still owned 'The Katzenjammer Kids' by title, he had no exclusive rights over the characters, allowing Dirks to relaunch his hit comic in another paper, under a different title.

The Katzenjammer Kids: post-Dirks period (1914-2006)

As soon as the legal issues regarding the copyrights of 'The Katzenjammer Kids' had been cleared, new episodes started running in The New York Journal from 17 May 1914 onwards. An anonymous ghost artist drew the series for six months, until on 29 November 1914, when he was finally credited as Harold Knerr. Knerr had previously drawn a 'Katzenjammer Kids' rip-off for The Philadelphia Inquirer, called 'The Fineheimer Twins' (1902-1914). In terms of characters, graphic style and even its "German English" language gimmick, 'The Fineheimer Twins' was almost a carbon copy of Dirks' comic. In that regard, Knerr was the perfect artist to continue the actual 'Katzenjammer Kids' series.

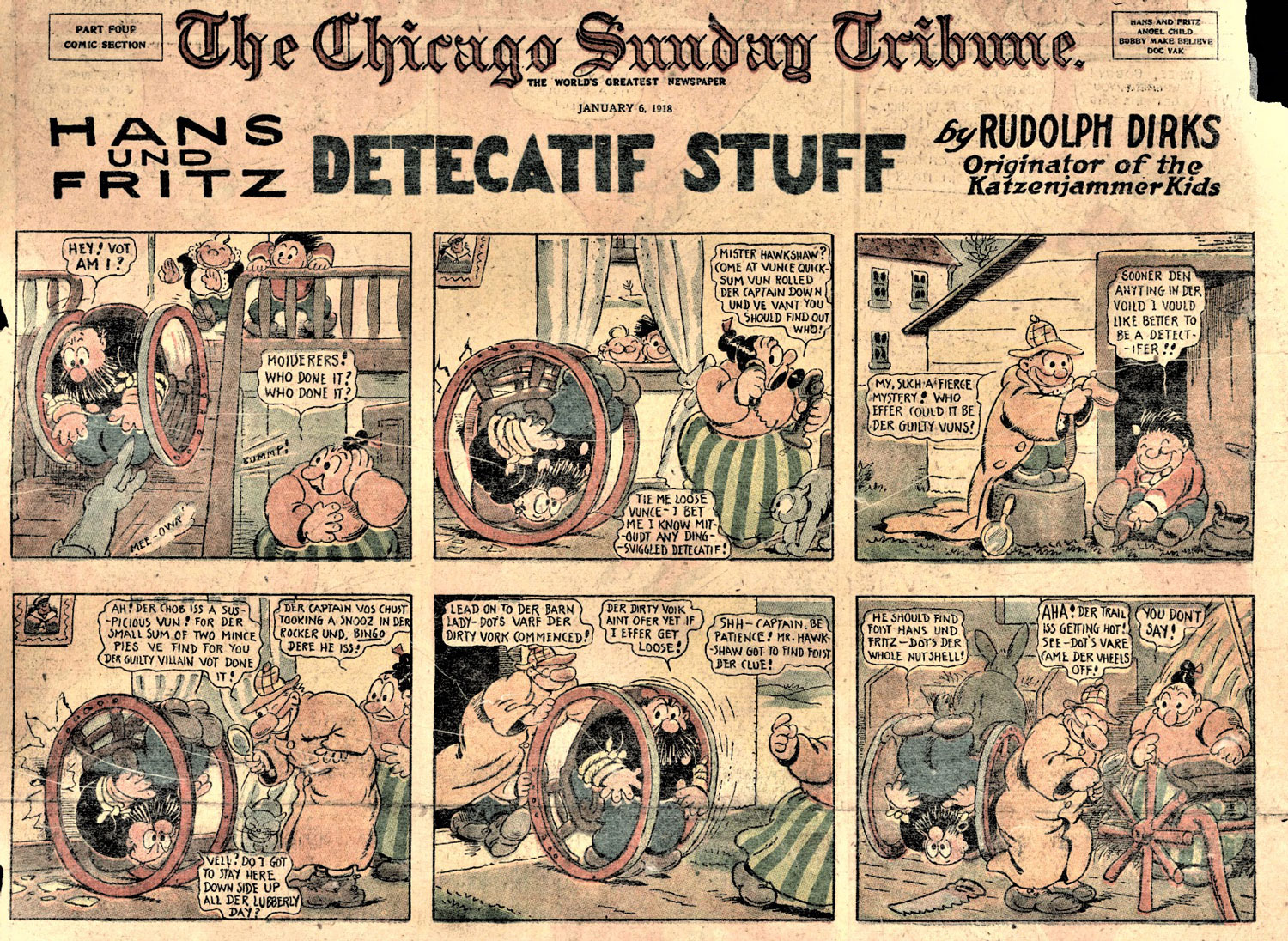

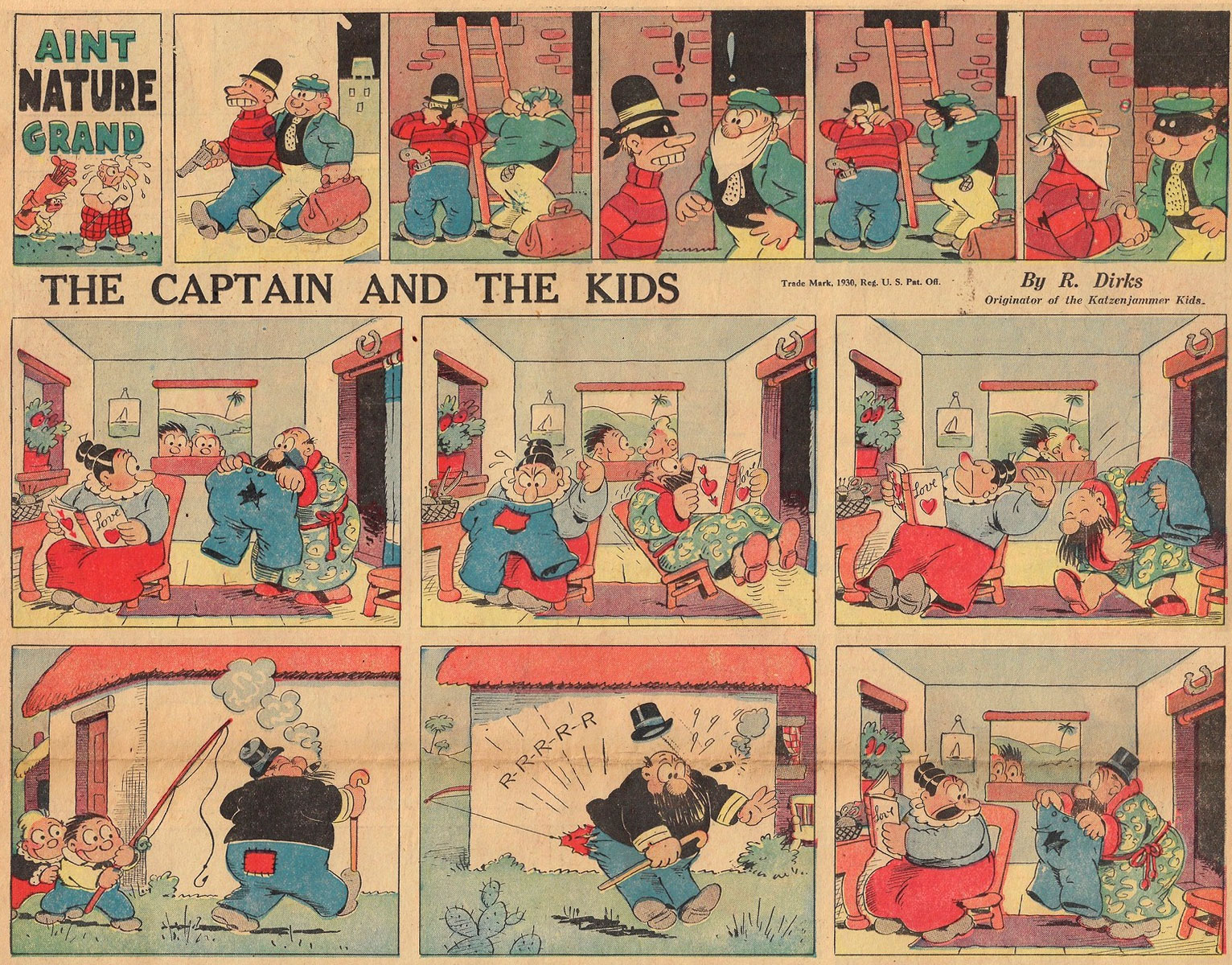

When Rudolph Dirks launched his new strip, the credit byline initially said "Rudolph Dirks, originator of the Katzenjammer Kids' (The Chicago Sunday Tribune, 6 January 1908).

Knerr's version was specifically promoted as 'The Original Katzenjammer Kids' to distinguish it from Dirks' simultaneously running reboot in The New York World and The Sunday Star (first as 'Hans and Fritz' then as 'The Captain and the Kids'). Only between 23 June 1918 and 11 April 1920, Knerr's 'The Katzenjammer Kids' was briefly retitled to 'The Shenanigan Kids' because of the anti-German sentiment in the wake of World War I. The characters were now described as Dutchmen "from Edam", with Hans and Fritz taking the names Mike and Aleck. After two years, the original title and ethnicities returned. 'The Katzenjammer Kids' remained German, even when new anti-German sentiment rose during World War II. Knerr did an excellent job in capturing the overall style of Dirks' original comic. His version of 'The Katzenjammer Kids' maintained its popularity, while the artist also added a personal touch. He introduced new characters like the African king Bongo (1935), the British governess Miss Twiddle (1936), her little niece Lena (1936) and the mischievous model student Rollo Rhubarb (1936).

Besides the 'Katzenjammer Kids' Sunday comic, a daily comic version was launched on 28 May 1917, titled 'The Katzies'. Drawn by Oscar Hitt and ghosted by John Campbell Cory, this spin-off only lasted until 1919. A possible explanation for its lack of durability may have been that the daily spin-off left little room for much graphic detail. The comedy was therefore more verbal, even though a large part of the Sunday comic's appeal was its slapstick and pranks. There was also a topper comic, 'Katzenjammer Kut-Outs', which Knerr drew from 4 September 1932 until 10 March 1935.

In the 1940s, several Sunday comic episodes of 'The Katzenjammer Kids' were ghosted by Stan Asch. After Harold Knerr's death in 1949, the series was taken over by Doc Winner, who added a new recurring character to the cast, the romantic swindler Fineas Flub. On 29 July 1956, Winner passed the pencil to Joseph Musial, who drew 'The Katzenjammer Kids' from then until his death on 31 July 1977. Between 7 August 1977 and 1982, Mike Senich continued Hans and Fritz' seemingly never-ending pranks, until he was succeeded by Angelo DeCesare (1982-1986) and, from 1986 on, Hy Eisman. Eisman drew 'The Katzenjammer Kids' for the next 20 years, until the final new episode saw print in 2006.

Debuting in 1897 and only ending in 2006, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' outlasted its creator longer than any other series. As of today, it remains the longest-running comic series of all time. Frank King's 'Gasoline Alley' (in syndication since 1918) is second in place, followed by Billy DeBeck's 'Barney Google & Snuffy Smith' (since 1919) and E.C. Segar's 'Thimble Theatre' (better known as 'Popeye', since 1919) are in a shared fourth place. All these years, 'The Katzenjammer' had been in non-stop production, with the exception of the March 1913-May 1914 period, when the legal battle between Rudolph Dirks and William Randolph Hearst forced the paper to rely on reprints. While 'The Katzenjammer Kids' hasn't printed new gags since 2006, reprints still appear in some newspapers, making it still the oldest comic strip in continuous syndication. It also holds the record as the only comic to have run in three centuries.

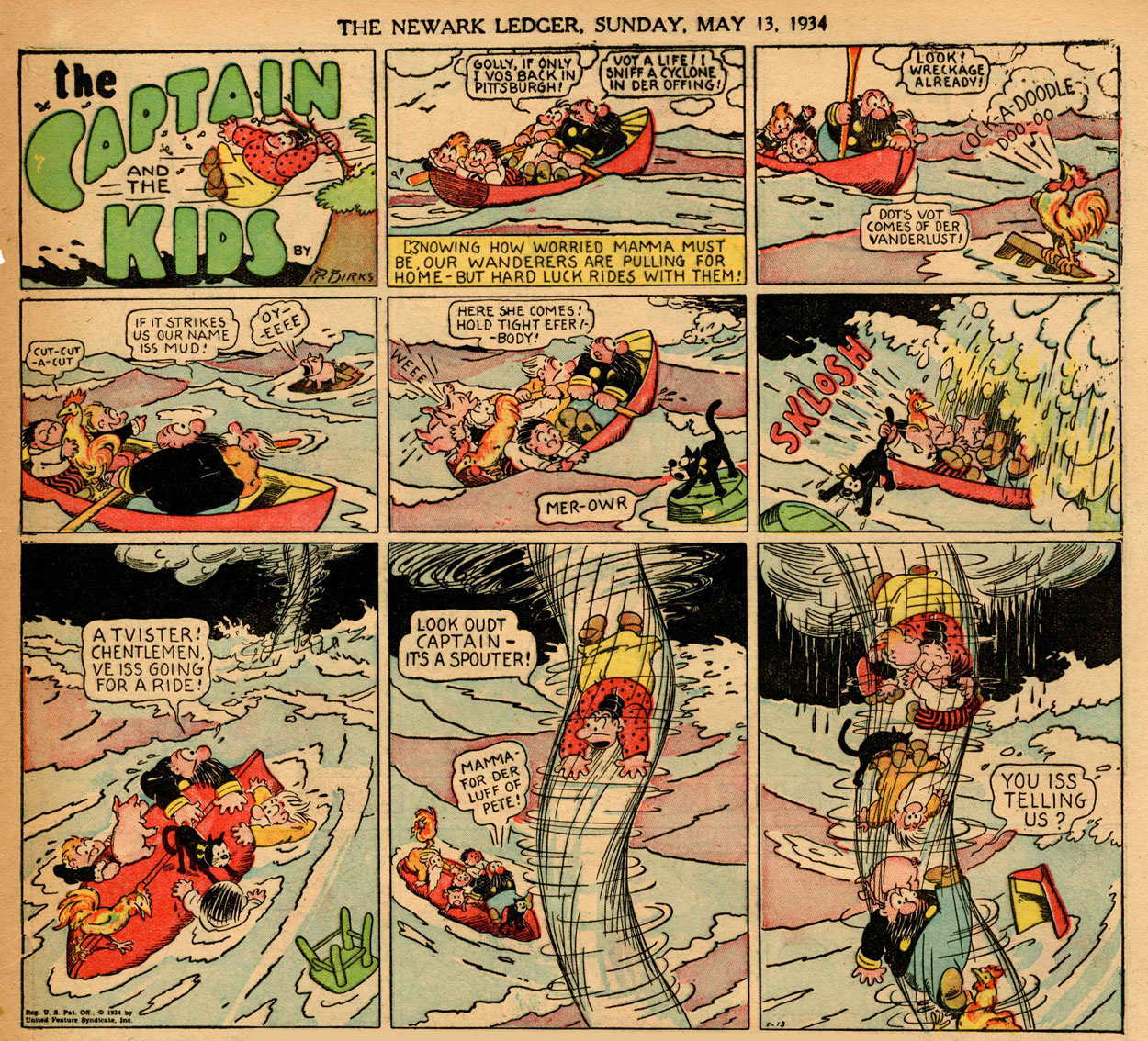

'The Captain and the Kids' of 13 May 1934.

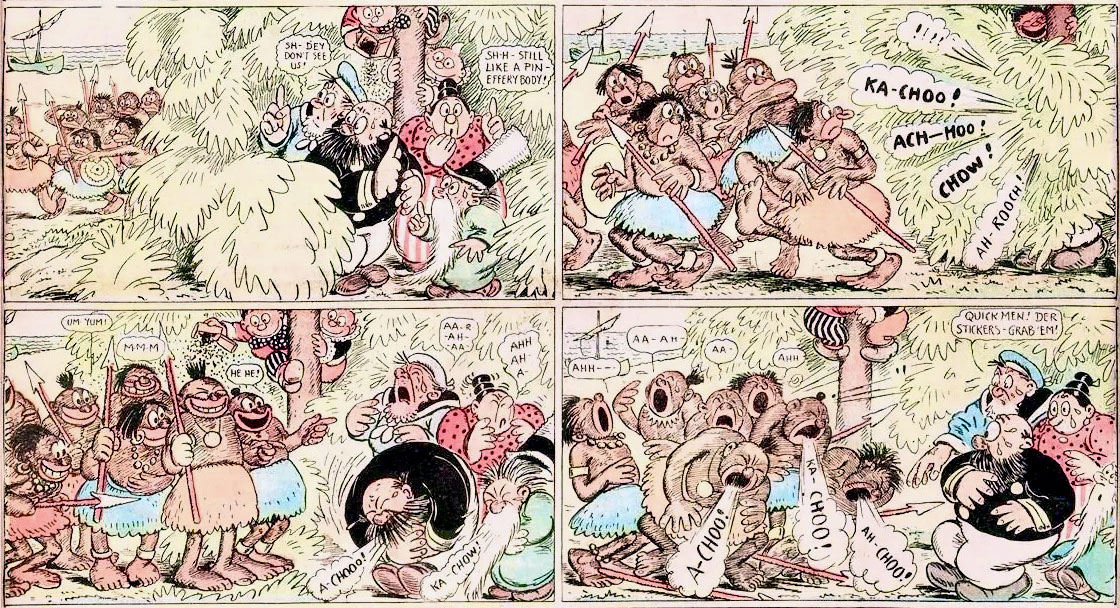

The Captain and the Kids

After winning back the rights to his 'Katzenjammer Kids' creations, Rudolph Dirks relaunched his hit comic on 7 June 1914 on in Joseph Pulitzer's The New York World. Syndicated by Press Publishing, it simultaneously ran in the Sunday supplement of The Evening Star, The Sunday Star. However, Dirks couldn't use the name 'The Katzenjammer Kids', since it was still owned by the previous publisher, William Randolph Hearst. For the first 11 months, each gag ran without a proper title, but with the byline "By the originator of the Katzenjammer Kids". Sometimes the series was titled 'Bad Boys', but from 23 May 1915 on, Dirks recycled the title he had used during the early days, 'Hans und Fritz'. However, when the United States entered the First World War in 1917, anti-German sentiment grew. Much like Harold Knerr's 'The Katzenjammer Kids' was renamed to 'The Shenanigan Kids' and the boys' nationality changed from German to Dutch, Dirks was forced to do the same. From 25 August 1918 on, 'Hans und Fritz' was rebaptized as 'Bad Boys: The Captain and the Kids', a title by 1919 permanently shortened to 'The Captain and the Kids'. After the war ended and Germanophobia eventually died down, Knerr's 'The Shenanigan Kids' became German-Americans again in 1920 and were retitled back to 'The Katzenjammer Kids'. Dirks' characters were renaturalized that same year, but remained known as 'The Captain and the Kids'. Initially, 'The Captain and the Kids' was distributed by the New York World's own syndicate, Press Publishing. Starting in 1931, the syndication rights were acquired by the E. W. Scripps Company, who distributed the comic through The World Feature Service and, starting on 1 January 1933, the United Feature Syndicate. Topper strips have included 'History Repeats It's-Self' (11 April - 9 May 1926), 'Have You A Little Cartoonist In Your Home?' (14 November 1926 - 30 December 1929) and 'Ain't Nature Grand' (5 January 1930 - 6 December 1931).

'Ain't Nature Grand' topper with the start of a 'Captain and the Kids' gag (18 May 1930).

Throughout the simultaneous run of 'The Captain and the Kids' and 'The Katzenjammer Kids', Rudolph Dirks and Harold Knerr were in constant competition with each other. It led to an ironic situation where Dirks (who originally copied Wilhelm Busch) and Knerr (who originally copied Dirks), now started to imitate each other. 'The Katzenjammer Kids' and 'The Captain and the Kids' barely differed in terms of cast, comedy, language and style. Even new plotlines and side characters were copied. If the cast in one of the dueling comics traveled to a certain exotic location, within a week, the same thing was bound to happen in the rival comic. Back when Dirks drew 'The Katzenjammer Kids', he had introduced pirate captain John Silver in the series, based on Long John Silver from Robert Louis Stevenson's classic novel 'Treasure Island'. At a certain point, Knerr fished up this character again and gave him a prominent new role. Since Dirks couldn't use the same character, he quickly introduced a similar buccaneer, which he named Captain Bloodshot. In 1935, the Katzenjammer Kids stranded on the tropical Squee-Jee Islands, ruled by King Bongo. In 'The Captain and the Kids', Dirks named it the Cannibal Islands and also added an African monarch. Eventually, this constant mirroring reached a point where readers had trouble telling the two series apart. Indeed, only a few characters by Dirks weren't used by Knerr. One of these creations were Ginga Dunn, a self-important, turban-wearing, bearded Indian trader who talks in rhyme. His name is a pun on the 1890 poem 'Gunga Din' by Indian novelist Rudyard Kipling.

'The Captain and the Kids' of 15 August 1915.

Comic fans have often compared Dirks and Knerr's series, with several arguing which one of them was superior. A slight positive bias has always gone to Knerr, who had the advantage of being a lifelong bachelor who could devote all his time and energy to the little universe in 'The Katzenjammer Kids'. In terms of market value and global syndication, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' always outdid and eventually outlasted 'The Captain and the Kids'. Dirks always felt as if his hit series was taken away from him. Even though he could still work with his own characters, he couldn't use the title 'The Katzenjammer Kids' any longer, making it seem as if he was merely drawing a rip-off, while actually being the original creator. Such frustrations undoubtedly could offer an explanation why, after 1914, his heart wasn't always into it. During the early 1920s, he was assisted by Oscar Hitt, who had previously drawn both the 'Katzenjammer Kids' imitation 'Mama's Darlings' (1917-1918) in the Chicago Herald and the official 'Katzenjammer Kids' daily strip, 'The Katzies' (1917-1919). When working for Dirks, Hitt briefly drew new 'Captain and the Kids' episodes on his own in 1922. During this decade, Perce Pearce also ghosted on the series. Between 24 April 1932 and 31 December 1933, Dirks had a contractual dispute with United Feature and refused to work on 'The Captain and The Kids'. His assistant Bernard Dibble drew the series during this period, and introduced a new character named The Brain, a masked villain in top hat who has a masked stork for a pet. Between 19 March 1934 and 1939, the Sunday comic of 'The Captain and the Kids' also received a daily spin-off comic, again drawn by Bernard Dibble.

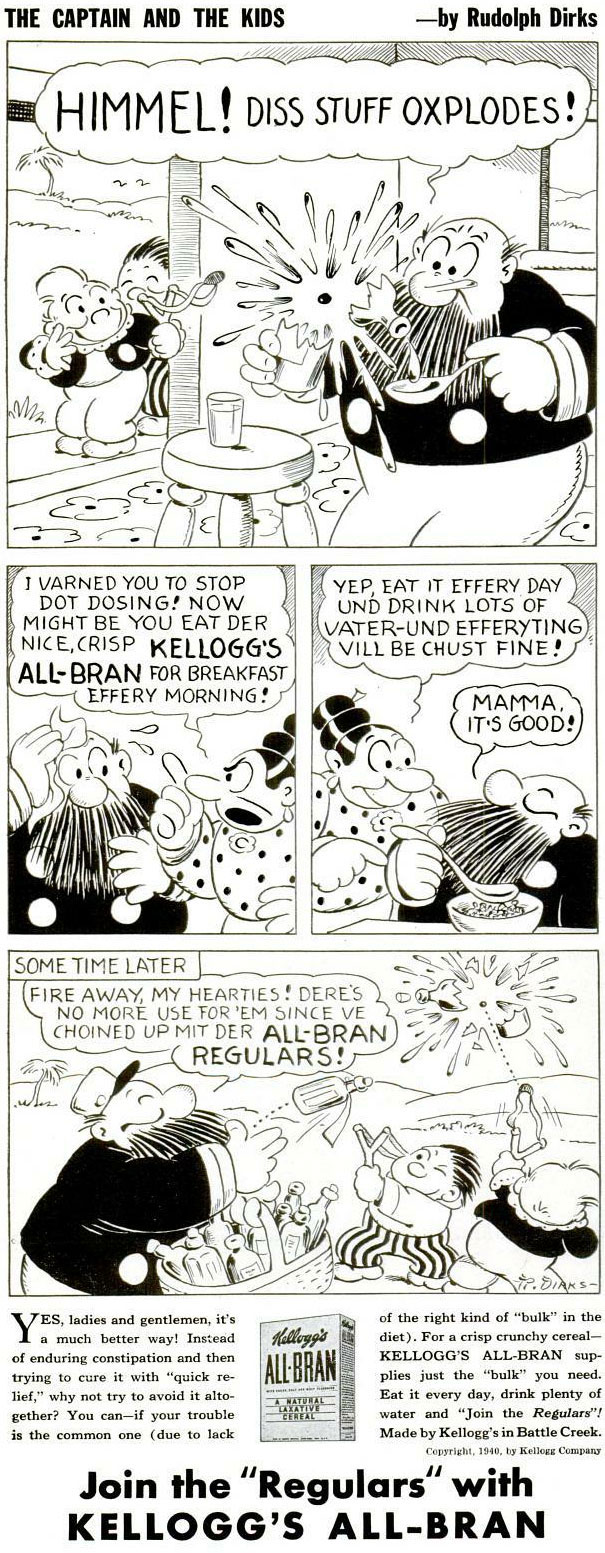

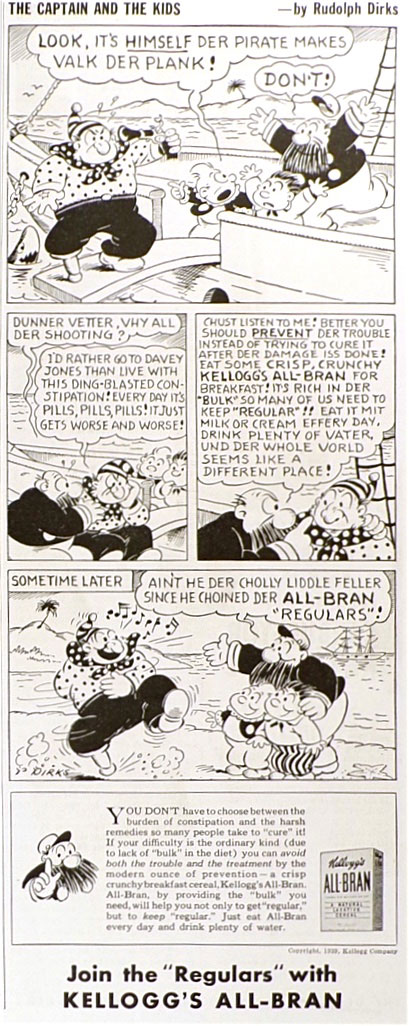

Advertising strips with 'The Captain and the Kids' for Kellogg's (1930s).

On 7 January 1934, Rudolph Dirks returned to 'The Captain and the Kids', but focused solely on the Sunday comic. He introduced only one major new character during this era, a grouchy hermit. Between 1941 and 1955, the series was also featured in comic books released by Sparkler Comics. In 1947, 'The Captain and the Kids' received its own individual comic book title, first published by United Feature and later by Dell Comics. Creators of new material for these 'Captain and the Kids' comic books were Jack Mendelsohn and Paul Newman (writers between 1958 and 1961) and Peter Wells (writer/artist around 1952). 'The Captain and the Kids' was also translated in Swedish as 'Pigge och Gnidde'.

After World War II, in 1946, Dirks' son John Dirks became his main assistant. He brought a fresh take to the series, introducing more outlandish storylines that brought the cast to the Abominable Snowman and into outer space. In 1962, Rudolph Dirks retired, while John continued 'The Captain and the Kids' until the final episode ran in papers on 15 April 1979.

Fine arts

Outside of his career as a newspaper comic artist, Dirks was also active as a realistic painter. With his 1908 painting 'The Fledglings', he went down in history as the first artist to depict aircraft flight. On 3 November 1908, he visited an aerodrome at Morris Park in New York City, where people worked on gliders, kites and balloons. Although nobody actually went up in the air, Dirks still immortalized the event in an oil painting. His paintings were exhibited during the 17 February-15 March 1913 Armory Show in New York City, incidentally also the first exhibition of modern art in the U.S. Other cartoonists who also exhibited their art during this event were Herbert Crowley, Walt Kuhn, George Luks, Gus Mager and Marjorie Organ. Dirks also established an artistic colony in Ongunquit, Maine.

Death

In 1968, Rudolph Dirks passed away in New York City at the age of 91. According to legend, he died with a cocktail glass in hand, his last words being: "I want a cherry".

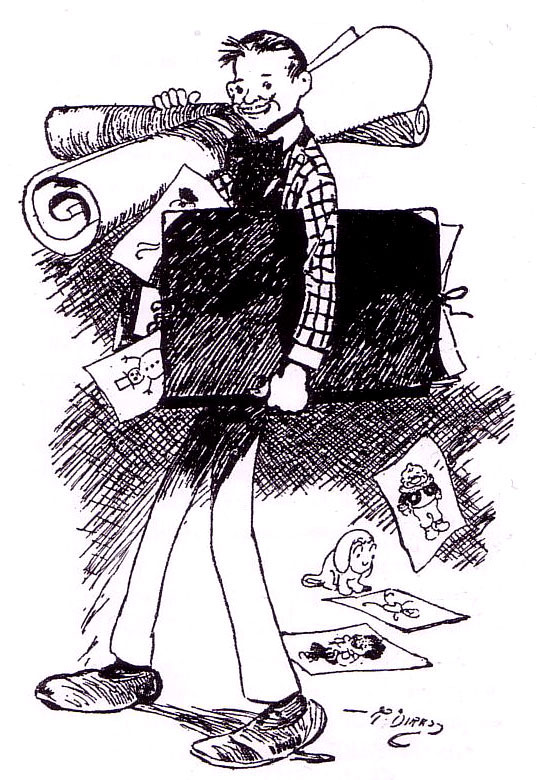

Early self-portrait.

Legacy and influence

Rudolph Dirks remains one of the key figures in the history of comics. As a pioneer in the use of cartoony visuals and speech balloons, his impact and influence changed the development of the medium to such a degree that it cannot be imagined without him. As 'The Katzenjammer Kids' became a hit and his production tempo increased, Rudolph Dirks settled on a simpler, more loose style. His characters received more caricatural faces, with big eyes, bulbous noses, stubby fingers and toes, and huge round shoes. This style helped him reach his deadlines quicker and was also more pleasing to draw. Many newspaper comic artists in the early 20th century have been influenced by this graphic look, like Frederick Burr Opper, Oscar Jacobsson, George Herriman, Billy DeBeck, Russ Johnson, Rube Goldberg and E.C. Segar. Particularly Hans and Fritz' facial designs can be recognized in many early 20th-century comic characters, like Opper's Happy Hooligan, James Swinnerton's Mr. Jack and Oscar Jacobsson's Adamson. Later generations of cartoonists have also picked up this retro style, with Jack Davis, Ronald Searle, Mort Walker, Don Martin, Robert Crumb, Dik Browne, Philip Guston, Patrick McDonnell and Richard Thompson as only a few examples. Stan Drake, observing Dik Browne using the typical Dirks style, gave it its current nickname, "big foot style".

Since Dirks wanted to emphasize the "Germanness" of his characters, dialogue became more important. While Charles Saalburg's 'The Ting-a-Lings' and Richard Outcault's 'The Yellow Kid' were the first American newspaper comics to use speech balloons on a regular basis, their series were short-lived and their success limited to the United States. 'The Katzenjammer Kids' popularized balloon comics to such an extent that it became the dominant style. Almost every newspaper comic artist in the USA switched to using them instead of text captions. And when Dirks' comic started to be translated, it further promoted the style in the rest of the world. Various 20th-century comics also imitated eccentric speech for their characters, most notably in the work of George Herriman, E.C. Segar, Al Capp and Walt Kelly. Germanized English as a gimmick also popped up in Harold Knerr's 'The Fineheimer Twins' and 'Dinglehoofer and His Dog', and in Harry George V. Hobart and Harry James Westerman's 'The Dinkelspiels'. The Dutch comic artist Marten Toonder took inspiration from Inspector for the character of Professor Zgbygniew Prlwytzkofsky in his 'Tom Poes' comic, who shares the same design (long beard, high hat) and also speaks in pseudo-German.

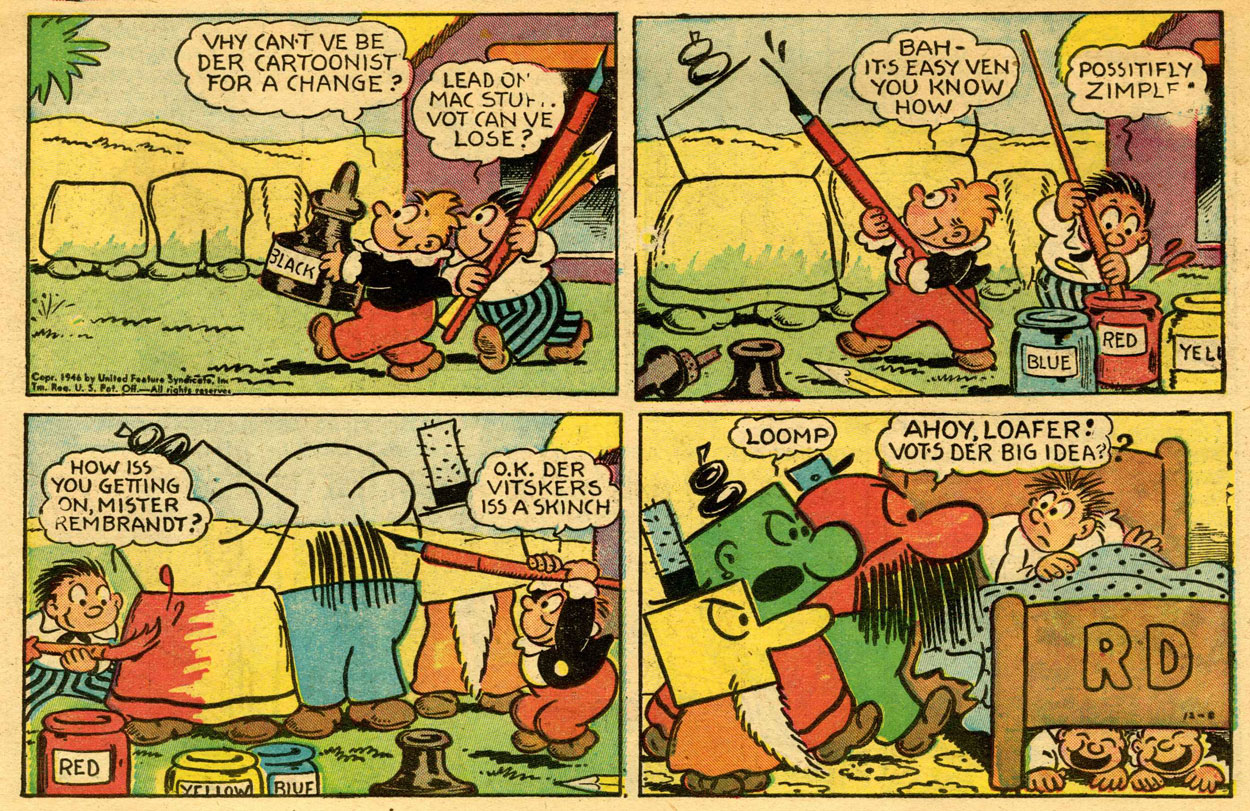

Meta humor in 'The Captain and the Kids'.

Dirks introduced several other techniques that gave his comic a more vital look. His early gags feature successive scenes without borders. Gradually, he started drawing panels around the images to distinguish them from each other, which benefited the reading experience. He also came up with many striking visual ideas. When a character runs, he leaves straight lines and a cloud of dust behind, indicating speed. If he is kicked in the behind, a footprint is left on his buttocks. Since cartoonists couldn't use curse words in their stories, Dirks let them yell typographical symbols or tiny thunder clouds or weapons instead. Half a century later, Mort Walker named such symbols "grawlixes". In Dirks' comics, emotions also received visual exaggerations. Nervousness is implied by having little sweat drops spurt from a character's face. If a character cries, he will leave a small pool of tears on the ground. In pain, he will see tiny stars. When a character is angry, lightning bolts shoot from his or her eyes (an idea pioneered by Wilhelm Busch in a 1861 gag comic, but further developed by Dirks). Just like Busch, Dirks made use of visual metaphors and onomatopoeia to imply certain sounds. For instance, if somebody sleeps, a huge letter "Z" appears. When he snores, a thought balloon with a log being sawed in half emerges. Many of these ideas were picked up by other comic artists and also used by new generations, to the point of becoming standard comic iconography. Nowadays, only few people are aware that Dirks invented or at least popularized the majority of them.

Together with Wilhelm Busch's 'Max und Moritz', Rudolph Dirks' 'The Katzenjammer Kids' can be considered the "ur-example" of a gag comic, particularly the "trickster kid" subgenre. During the 1900s and 1910s, there were already dozens of 'Katzenjammer clones' in syndication all over the world. Remarkably enough, one of such clones was created by Rudolph Dirks himself! Between 16 September 1900 and 6 January 1901, he drew a strip called 'The Pinochle Twins' for the Philadelphia Inquirer, which had the same kind of set-up as 'The Katzenjammer Kids'. Starting in January 1901, it was taken over by Clare Dwiggins. Among the other American comics that borrowed from 'The Katzenjammer Kids' were were Hugh McCreas 'Jim and Jam' (year unknown), Gustave Verbeck 's 'Easy Papa' (1902), DeVoss Woodward Driscoll's 'Der Kidders und der Kolonel' (1904-1905), C.W. Kahles' 'Tim and Tom, The Terrible Twins' (1905-1906), Hy Leonard's 'The Triplet Boys' (1905), Karl (Ralph Hershberger's' 'Dem Boys', 1914-1918), Bow Wow (possibly Art Bowen)'s 'The Beelzebub Boys and Uncle Tom' (1902), Harold Knerr's 'Die Fineheimer Twins' (1903-1914), Inez Townsend's 'Snooks and Snicks' (1913-1915), Harry George V. Hobart and Harry James Westerman's 'The Dinkelspiels' (1913-1914), Gene Carr's 'Major Stuff' (1914-1915), Oscar Hitt's 'Mama's Darlings' (1917-1918) and C.W. Kahles, Nate Collier, Lyman Young and George Rohlfing (Ring)'s 'The Kelly Kids' (1918-1927). In Europe, many similar strips popped up. In the United Kingdom, Frank Holland drew 'Those Terrible Twins' (1898-1900), Leonard Shields 'The Bunsey Boys' (1902) and an anonymous artist created 'The Twinkerton Twins'. In Norway, there were Kristoffer Aamot and Jan Lunde's 'Skomakker Bekk og Tvilligene Hans' (1919- ) and Sverre Knudsen's 'Mass og Lasse' (1919- ). In Portugal, Rocha Vieira drew 'Az Proezas de Necas e Tonecas' (1922). Other early 20th-century gag comics simply used one trickster kid as their protagonist, like Richard Outcault's 'Buster Brown' (1902-1921), Joseph A. Lemon's 'Wilie Cute' (1903-1906) and Inez Townsend's 'Gretchen Gratz' (1904-1905).

The line between inspiration and sheer plagiarism sometimes got blurred. As early as 1899, the Czech magazine Palecek traced an entire 'Katzenjammer Kids' gag, naming the boys Pepu en Ferdika. In the 24 August 1902 issue of the French magazine Amiens Memorial, an unknown artist named Jack copied one of Dirks' gags panel by panel. Two years later, in the 11 September 1904 edition, an artist with initials L.F. copied a gag by Dirks again, but redesigned Die Mamma and the Kids and added text underneath the images. In L'Album Comique de la Familie issue #42 of 1902, an artist named Bill traced an entire 'Katzenjammer Kids' gag, turning it into a text comic format. As far as Japan, 'Katzenjammer Kids' episodes were copied too, for instance by an unknown artist in the Japanese satirical magazine Joto Poncho, who made the gag 'Tonari no Oji-san' ('The Uncle Next Door'). Comic historian Ron Stewart presumes this artist may have been Kosugi Misai.

As the 20th century progressed, children's magazines all over the world launched their own, home-based gag comics about mischievous kids. In spirit, they all owed something to 'The Katzenjammer Kids', whether featuring one brat, a duo, or an entire gang. Just like Dirks and Knerr's series, the child protagonist(s) pranked adults, or each other on a weekly basis. Favorite targets were always teachers, police officers or their own relatives. Just like 'The Katzenjammer Kids', new episodes were generally featured on the front page of these magazines, as the child protagonists were typically the mascots of the publication too. Even the typical 'Katzenjammer Kids' title font, with the heads of all cast members appearing in a horizontal strip, was copied by some foreign artists. Spiritual successors could be found in the United States, like Gene Byrnes' 'Reg'lar Fellers', A.D. Carter's 'Just Kids' and Martin Branner's 'Perry and his Rinkydinks', but also in Europe. Prime examples from Belgium are Hergé's 'Quick & Flupke', Eugeen Hermans' 'Flipke en de Rakkers', Willy Vandersteen's 'De Vrolijke Bengels' and Marc Sleen's 'De Lustige Kapoentjes'. Further appearances occurred in France (Jean Tabary's 'Corinne et Jeannot'), The Netherlands (Frans Piët's 'Sjors en Sjimmie' and Jacobus Grosman's 'Gijsje Goochem'), Spain (Josep Escobar's 'Zipe y Zape'), Yugoslavia (Sergije Mironovic Golovcenko's 'Maks I Maksic') and the United Kingdom (Ronald Searle's 'St. Trinians' and Leo Baxendale's 'The Bash Street Kids').

Painting of his characters by Rudolph Dirks.

In the United States, Rudolph Dirks has influenced Bob Bolling, Gene Carr, Nate Collier, DeVoss Woodward Driscoll, Will Elder (who liked 'The Katzenjammer Kids' because he was prankster himself), Syd B. Griffin, Oscar Hitt, Russ Johnson, C.W. Kahles, Harold Knerr, Hy Leonard, Lank Leonard, Joseph A. Lemon, Frederick Burr Opper, Richard F. Outcault, George Rohlfing, John Severin, Inez Townsend, Harry James Westerman and Lyman Young. In Uruguay, he inspired Geoffrey Foladori.

In Europe, Dirks followers can be found in Belgium (Hergé, Eugeen Hermans, Marc Sleen, Willy Linthout), France (F'murr), The Netherlands (Marten Toonder), Norway (Sverre Knudsen, Jan Lunde, Henrik Rehr), Portugal (Rocha Vieira), Spain (Josep Escobar, Palmer) and the United Kingdom (Frank Holland, Leonard Shields). In Japan, Dirks inspired Rakuten Kitazawa, while in Australia Hugh McCrea was a direct follower. As early as the 1930s, 'The Katzenjammer Kids' were spoofed in pornographic parodies, as part of the Tijuana Bible phenomenon. In issue #20 of Mad Magazine (February 1955), Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder also spoofed 'The Katzenjammer Kids', while the French artist Roger Brunel made a pornographic parody in his 'Pastiches 2' comic book (1982).

During a breakfast scene in Ernst Lubitsch' classic comedy 'Heaven Can Wait' (1946), characters discuss a newspaper episode of 'The Katzenjammer Kids'. Stop motion animation director Art Clokey, famous for 'Gumby', was inspired by Dirks' comic to create Gumby's rivals, the Block-heads. A Norwegian band, Katzenjammer, and a French cabaret group, Katzenjammer Kabarett, took inspiration from the comic strip's title. Novelist Gertrude Stein and painter Pablo Picasso were celebrity fans. According to Stein's 'The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas', she and Toklas once gave Picasso a whole supply of Sunday comics featuring Dirks' comic strip, which he was utterly delighted by. However, his friend Fernande felt outraged that the famous painter kept them all to himself and said: "It's a brutality I will never forgive him for". Interviewed by Dave Shulman for L.A. Weekly (18 July 2007), Matt Groening said that the running gag in 'The Simpsons' where Homer strangles Bart was inspired by a 'Katzenjammer Kids' episode in which the Captain strangles Hans and Fritz.

In 1995, The Katzenjammer Kids were honored, among other classic American comic characters, on an official postage stamp by the U.S. Postal Service. In July 2009, a street in Rudolph Dirks' birth town Heide was named after him. On 13 July 2012, Rudolph Dirks was posthumously inducted into the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame. His name also lives on in an annual award for comic artists in Germany, the Rudolf Dirks-Preis.

Books about Rudolph Dirks

For those interested in Dirks' life and career, Tim Eckhorst's biography 'Rudolph Dirks; Katzenjammer, Kids & Kauderwelsch' (Deich Verlag, 2012) is highly recommended. In 2019, Eckhorst and director Martina Fluck made the documentary 'Katzenjammer Kauderwelsch', in which he travelled to the USA to find out more about Dirks' life and career, interviewing then-current 'Katzenjammer Kids' artist Hy Eisman in the process. The documentary was also released on DVD. Eckhorst later also brought out the catalogue 'Katzenjammer: The Katzenjammer Kids: Der älteste Comic der Welt' (Avant-Verlag, Berlin, 2022), co-written with Alexander Braun.