Comics History

History of Bulgarian Comics

Now that Bulgarian contemporary art is well on its way to being integrated into world culture, Bulgarian comics should be granted their rightful place among Bulgarian art, culture and library collections.

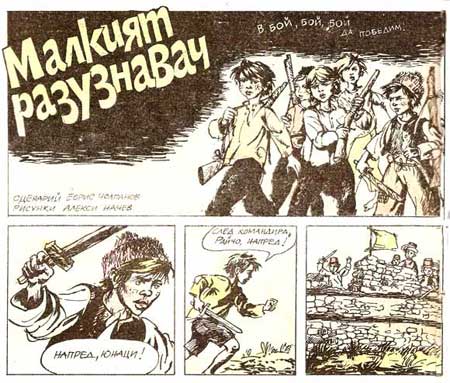

Regretfully, due to a variety of reasons, comics have been cursed as an artform in Bulgaria for many years now. While they flourished during the first half of the 20th century, artists were sometimes victim of government censorship or arrest if their work had too much political undertones. This forced most Bulgarian comic artists to make mainly children's stories, which only added to the lack to their social stigma and lack of serious artistic interest. After a period of very fruitful development during the 1980s, Bulgarian comics plunged deep into the underground and virtually disappeared from kiosks and bookshops. Right now, if you look for a definition of "comics" in any Bulgarian dictionary (or any Bulgarian equivalent of the word), you won't be able to find one, not even in specialized reference works. Only the "Dictionary of Foreign Words in Bulgarian Language" gives a vague explanation of what comic art is, but the definition is so ignorant and ridiculous that it's not worth quoting. Nevertheless, the history of comics in Bulgaria is a fascinating one.

-classic (pre-World War II)

-classic (1940s onwards)

-revival (1980s)

-post-industrial

1890-1940

Bulgaria's comics culture started very late compared with other European countries. In 1890 the famed photographer and revolutionary Georgi Danchov worked as a cartoonist for the magazine Talasum. It was here that he created a picture story named 'The Six Feelings', which shows two men in a restaurant. Each picture has the feeling in question described in one line beneath the drawing. The illustrations also show a clear passage in time and what could be described as a narrative. In other words: this is the oldest Bulgarian comic worthy of this honorific title. In 1906 Slavov created a comic strip based on the poem 'Gordelivata Maca' ('The Proud Pussycat'), which appeared in the children's magazine Slaveiche ('Nightingale'). Another early comic artist was cartoonist and caricaturist Aleksandar Bojinov who created picture-stories like 'Bulgarian' and 'Azbuka za Malkite' ('Alphabet for Children'). Caricaturists like Ilia Beshkov, Aleksandar Dobrinov and Raiko Aleksiev occasionally made use of illustrated narrative sequences in their caricatures. Even back then their ridicule of people in power often led to their arrest.

1940: Chuden Sviat and other comics magazines

Prior to World War II the Bulgarian scene had several monthly magazines for kids and also a specialized newspaper, Vessela Drujina, which occasionally featured comics. On 6 June 1940 the first issue of Chuden Sviat ("Wonderland") was published in Sofia, an all-comics color newspaper edited by Nikola Kotov, who was greatly influenced by Walt Disney comics. The contributors were some of the best Bulgarian writers of children's literature at that time: Orlin Vasilev, St. C. Daskalov, Angel Karaliichev, Georgi Raichev and others. Artists were Gogo Aleksiev, Aleksandar Denkov, Nikola Kotov, Iurdan Stubel, Pena Geneva, Stoian Venev and Georgi Atanasov. Vadim Lazarkevich created two text comics for Chiuden Sviat, 'Vesel Putniks Balon' and 'The Little Barber'.

Bulgarian comics around this period were mainly influenced by American comics like 'Tarzan', gangster comics and pirate comics. Another considerable influence was the Italian Disney comics magazine Topolino.

The most successful comics were the ones featuring scenes and fairy tales from Bulgarian folklore, or well-known classic novels and stories like 'Treasure Island' by Robert Louis Stevenson, which was adapted for comics by Liuben Zidarov. Zidarov also drew the western series 'Ulcheda' for the same magazine.

Kartinen Sviat ("Pictoral World") appeared on Wednesdays and was the first magazine to publish Bulgarian material, among others by Zvezdelin Conev, G. Georgiev and Vladislav Milev.

Kartinen sviat

1944: the communist regime

All of these magazines were cancelled from 9 September 1944 on, when the Bulgarian monarchy was toppled by rebels who established a communist republic. In the chaos many "enemies of the state" were arrested and executed. One of the victims was caricaturist Raiko Aleksiev, who had ridiculed Joseph Stalin many times in his work. Aleksiev was arrested and beaten up by police officers, until he died from his wounds. He was only 51 years old. Posthumously his name has been rehabilitated. In his home country an avenue and a gallery are named after him. In Antarctica there is even a glacier which bears his name.

Still, Bulgaria's new communist regime brought along many restrictions. Only a few foreign comics were allowed publication in the country, mostly innocent children's stories like Disney's. Bulgarian artists were also expected to just draw non-political and non-offensive comics, which greatly limited some artists' possibilities for self-expression. But like many Eastern-European and Russian comic artists during the Cold War era some still managed to sneak in sly satire of Communist politics, bureaucracy and dreams of liberty and democracy. In the second half of the 20th century new Bulgarian comics magazines would arise, such as Duga, Diaskop and the new edition of Chuden Sviat.

'Romani v Kartini' was a series of about 16 comic books published by the printing house Doverie in Sofia. There are different stories by different artists.

Based on a series of articles by Georgi Chepilev in the 1980s, Bulgarian comics can be divided in the following genres:

1) historical - patriotic

2) textbook

3) adventure (that later evolved into 'fiction'')

4) adventurous

5) curious

6) satiric (menipov)

7) sentimental - touching

8) instructive for kids

Bulgarian comic artists in the Comiclopedia

(Overview courtesy of Vladimir Nedialkov, with additions by Stiliana Thepileva. Edited by Kjell Knudde.)