Wilhelm Busch was a 19th-century German novelist, poet, playwright, caricaturist, painter, illustrator and prototypical comic artist. As one of the medium's true pioneers, he elevated the art of comics through his sophisticated writing style and dynamic drawings. His legacy rests on his iconic series 'Max und Moritz' (1865), about two boys who play tricks on adults. The godfather of all "trickster kid" gag comics, 'Max & Moritz' was a huge bestseller, translated all across the globe and inspiring many similar series, including Rudolph Dirks' equally iconic and influential 'Der Katzenjammer Kids' in the USA. 'Max und Moritz' proved that children were an important demographic for comics, which has been a blessing and a curse for the medium ever since. A versatile author, Busch made several picture stories without words, also known as pantomime comics. Other stories were accompanied by witty, ironic and moralistic rhyming couplets underneath the images. Some of his longer narratives can be regarded as early examples of graphic novels/comic books, besides 'Max und Moritz' also 'Hans Huckebein' (1867-1868), 'Antonius von Padua' (1870), 'Die fromme Helene' (1872), 'Tobias Knopp' (1875-1877), 'Fipps, Der Apfe' (1879) and 'Plisch und Plum' (1882). Busch also perfected the one-page gag comic, tightening comedic situations towards a well-staged punchline. He additionally introduced and popularized several hallmarks of modern-day comics, like alliterative names, onomatopoeia and expressive movement lines. Busch also wrote history as the first comic artist to be the subject of controversy, bannings and a media scare. His work has an anti-authoritarian streak, with several stories about kids tormenting adults, or ones mocking the Church, upper class society and moral crusaders. Together with Rodolphe Töpffer, Charles Henry Ross & Marie Duval, Richard F. Outcault and Rudolph Dirks, Wilhelm Busch ranks among the key figures in the early history of the comic medium. Together with Töpffer, Lyonel Feininger, Winsor McCay and George Herriman, he is one of the earliest comic pioneers whose work is considered high art. As the first significant comic artist in German-language history, Busch also remains a towering figure in general German literature.

Early life and career

Heinrich Christian Wilhelm Busch was born in 1832 in Wiedensahl, back then part of the Kingdom of Hanover, but nowadays located in Germany. He grew up as the eldest son of a shopkeeper who had seven children. With many mouths to feed, Busch's parents entrusted him to the care of his maternal uncle and aunt, who had a school in Ebergötzen. They remained responsible surrogate parents throughout Busch's further life and career, helping him whenever he was in need. In 1847, Busch moved to Lüthorst and studied mechanical engineering at the Hannover Polytechnic, but never finished the course. In 1851, he convinced his parents he wanted to switch to the Düsseldorf Art Academy instead. However, halfway through his year, he continued his studies at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp instead. In the Belgian harbor city, he marvelled at paintings by 17th-century Flemish painters like Adriaen Brouwer, Frans Hals, Peter Paul Rubens and David Teniers. Busch made similar portrait and landscape paintings, but felt so dwarfed by the talents of these Old Masters, that he kept them away from the public. Only a few people were allowed to see them and only in the last decade of his life, did he organize his first public exhibition. Many canvases were left unsigned and archived in non-ideal conditions. If he disliked the end result, he burned them in his garden. Therefore, few have survived today.

By 1853, the completely broke Busch fell ill with typhus, dropping out of school again. He made another try at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, but eventually became more preoccupied with his various creative endeavors, like painting, collecting folk tales, writing opera librettos, short stories and drawing comics.

Early career as writer/cartoonist

Starting in 1853, Wilhelm Busch drew caricatures for the club magazine of the artistic organisation Jung München. He was noticed by publisher Kasper Braun, who brought out the satirical magazine Fliegende Blätter and the Münchener Bilderbogen picture story prints. Braun offered Busch freelance work, which allowed him to remain financially stable. Busch livened up the pages of the aforementioned two magazines with amusing illustrations and picture stories. While many of his contemporaries drew prototypical comics with stiff-looking action scenes, Busch's drawings were far more vivid and expressive. He invented various graphic techniques to visualize speed, gravity and weight. When a character moved, Busch drew little lines next to their arms and legs. If they moved their body back and forth, heads and limbs were multiplied. To imply that an object is zipping through the air, a dotted line was drawn behind it. Busch was also the first known comic artist to visualize drunkenness, hallucinations and hangovers. All these innovations kept readers invested in the story.

Since publisher Braun had a workshop for wood engraving, all of Busch's early picture stories were made with this technique. From 1876 on, his illustrations were photographed and transferred onto a photosensitive zinc plate, the 'Herr und Frau Knopp' story being his first to use this technique. Visually oriented, Busch typically drew first, so he could focus on the narration afterwards. Contrary to many other prototypical comic artists of his time, his texts weren't a mere afterthought. He gave his narration equal care and attention, using sophisticated words, with dry, ironic reflections on the mayhem depicted in his panels. Making matters more complicated, he also wrote everything in rhyming couplets. Another novelty was Busch's use of onomatopoeia. He often implies sound effects with self-invented words, a standard in many comics today. Yet Busch restricted them solely to the text captions underneath the images. Only in one story, 'Bilder zur Jobsiade' ('Pictures of the Jobsiad', Bassermann, 1872), a sound effect appears within an image, namely a trumpeter blowing the sound "Tu-nuth!". Busch's use of language offered a powerful suggestion that comics could, indeed, be both equally visually and verbally strong.

Throughout his career, Busch built up a reputation as a witty writer. Influenced by his Protestant upbringing and the philosophical teachings of Arthur Schopenhauer, he had a cynical view of mankind. He regarded people as inherently cruel, corrupt and hypocritical, a view shining through in his entire body of work. Many of his picture stories feature pranksters, bullies, thieves and frauds. People and animals rob, torment, hurt and downright kill one another. Children are frequently caned. Dogs, monkeys, mosquitoes and mice cause mayhem. Many scenes in his work are remarkably graphic, with depictions of blood, decapitations and disturbing death scenes. Sometimes poetic justice prevails, with the "villains" being killed in the end. But in other tales, they get away with their misdeeds. Either way, Busch's grim narratives often end with a bittersweet moral.

Picture stories in Fliegende Blätter

Between 1859 and 1871, Busch made several one-shot picture stories for the magazine Fliegende Blätter. In the two-panel picture story 'Übertriebene Gefälligkeit' ("Excessive Complacency", issue #744, 1859), a man's hat is blown away by the wind, but captured by a farmer on his scythe. His next tale, 'Wie die Kränzl-Bötin die ganze Woch mit ihrem kranken Maxl geplagt ist' ("How Kränzl's Teacher is Bothered by Maxl's Illness Throughout the Week", issue #763, 1860), visualizes various excuses why little Max was too ill or physically unfit to attend school that week: he was doing hard labor at home, leaving him exhausted. Although not really a story, the images are a chronological progression of thematically connected images. The pantomime comic 'Die Maus oder Die gestörte Nachtruhe' ("The Mouse, or the Disturbed Night Rest", issue #783, 1860) provides a genuine humorous narrative. In this comic, a couple hears a mouse and tries to capture the nasty little critter. But in the final panel, he's still at large, making a taunting gesture at them.

'Naturgeschichtliches Alphabet für grossere Kinder und solche, die es werden wollen' ("Natural History Alphabet for Children and Those who Want to Become One", issue #784, 1860) is an alphabetical overview of various animals and plants, accompanied by a little rhyme. Busch illustrated a joke in the two-panel 'Tandelnswerte Antwort auf eine wohlgemeinte Frage' ("Reprehensible Answer to a Well-Intentioned Question", issue #789, 1860), in which a boy says he's got "something in his throat”. When a woman asks him what it is, he replies: "A tongue”, and sticks it out. 'Schrekliche Folgen eines Bleistifts' ("Horrible Consequences of a Pencil", issue #792, 1860), is mostly a written story with three illustrations. It ends with a young couple accidentally stabbing each other to death with a large pencil when they embrace. 'Der Stern der Liebe' ("Love Star", issue #795) is another illustrated text, in which a young couple looking at the stars is contrasted with the same lovers in old age. At his advanced age, the senior can no longer remember the stars' names.

Pitch black comedy is found in 'Trauriges Resultat einer vernachlässigten Erziehung' ("The Sad Result of a Neglected Education", issue #796, 1860). The picture story centers on a spoiled rich brat, Fritzchen Kolbe, who verbally abuses and pranks a tailor named Böckel. Böckel frequently complains to the boy's parents, but they deny the seriousness of the problem. Eventually Böckel gets so fed up, that he decapitates Fritzchen with a gigantic pair of scissors. He dumps the corpse in a river, where it is gobbled up by a fish. The boy's clothing is stitched into a pair of pants, which Böckel sells to a store owner. Meanwhile, Fritzschen's mother catches the fish and is shocked to find her son's decapitated body inside. She falls on a large kitchen knife and dies. When Mr. Kolbe sees his dead wife and son, he takes a piece of snuff to calm his nerves, but sneezes so hard that he falls out of an open window, killing not just himself but also an old aunt passing by. The police arrests the store owner, since his pants are the same as Fritzchen's, and hang him. Only then is the tailor's ticket discovered, leading the authorities to the real culprit. In his cell, Böckel commits suicide by cutting off his own head with his scissors.

'Metaphern der Liebe' ("Metaphor of Love", 1861).

'Die Mohrenträne' ("The Moor's Tears", issue #797, 1860) is a written story, accompanied by four illustrations, depicting a black Moor, struck by lovesickness. In the two-panel 'Aus dem Regen in die Traufe' ("From Bad to Worse", issue #824, 1861) a man hides from the rain, but is unaware that his long coat hangs in a water barrel, forcing him to afterwards dry his clothing. A tale of unrequited love is subject in 'Metaphern der Liebe' ("Metaphor of Love", issue #830, 1861), where a sweaty man longs for an attractive woman, whose angry looks literally burn him to shreds. The picture story is notable for its early use of a lightning bolt to imply the woman's piercing look, a symbol many comic artists would later also use to express anger.

Busch returned to pantomime comedy with 'Das erste Bad im Freien' ("The First Bath Outdoors", issue #832, 1861), in which a man decides to swim in a lake to cool himself off from the hot weather. However, he quickly rushes back ashore, because leeches have attached themselves to his body. More aquatic horror can be found in the text comic 'Der Frosch und die beiden Enten' ("The Frog and the Two Ducks", issue #841, 1861). Two ducks try to catch a frog, but eventually get stuck, becoming easy prey for a butcher. In 'Die Ballade von den sieben Schneidern' ("The Ballad of the Seven Tailors", issue #842, 1861) seven tailors rob a woman, but all die, with the Devil hanging their souls (visualized as threads) to a tree. Whenever one hears the wind whistle, it's actually the tailors' voices. Mankind triumphs in 'Die Fliege' ("The Fly", issue #859, 1861), in which a man tries to capture an annoying fly, eventually crushing the insect flat. In 'Der hohle Zahn' ("The Hollow Teeth", issue #861, 1862), another poor guy is tormented by a toothache, wiggling in pain until a dentist finally pulls the tooth. Man's best friend turns out to be worthless in 'Der zu wachsame Hund' ("The Attentive Dog", issue #869, 1862), where a dog owner gets stuck in a ditch, but his pet prevents him from getting saved.

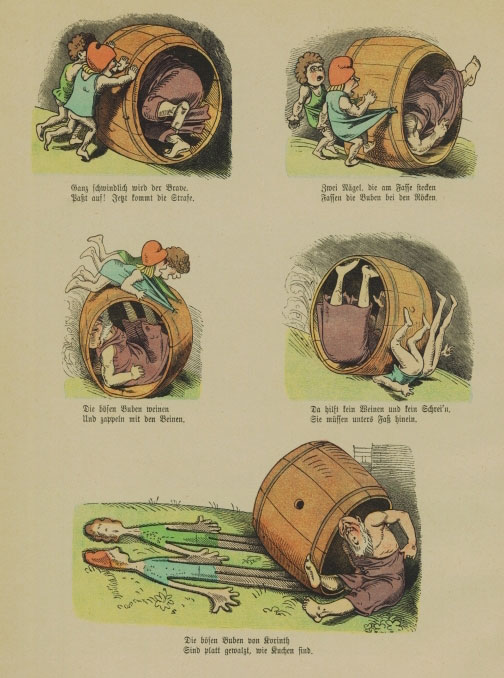

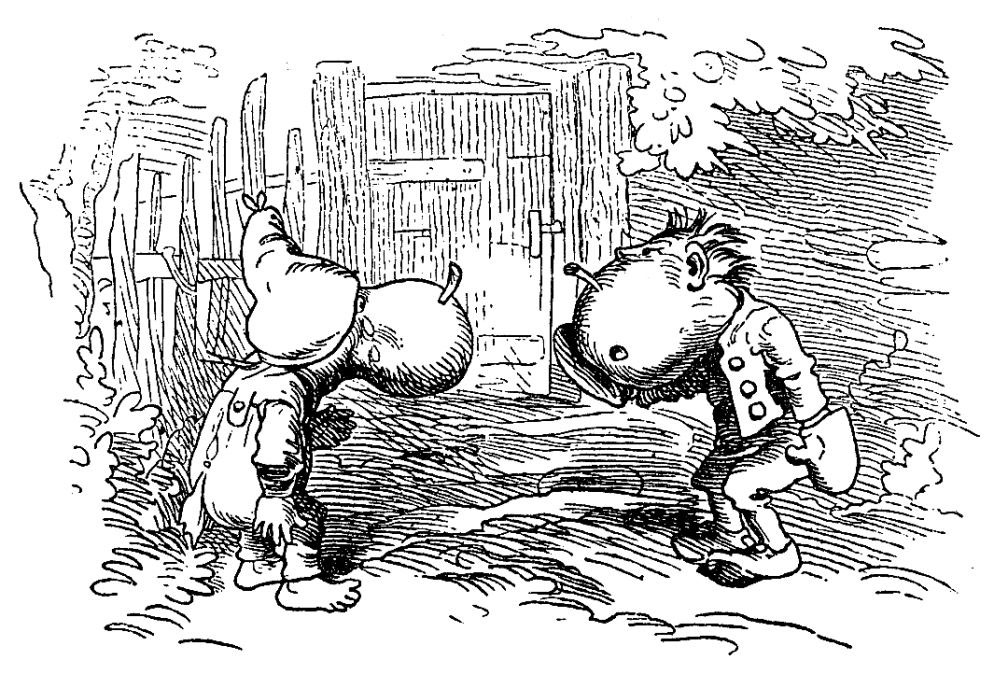

'Diogenes und die bösen Buben von Korinth' ("Diogenes and the Mean Kids from Korinthe", 1862).

Marital troubles take center in 'Wie der Mann um den Hausschlüssel bitten lernt' ("How Man Learns How to Ask for the House Key", issue #874, 1862). A man beats his wife until she hands over the house keys. Yet his coat gets stuck between the door, leaving the pocket with his key in it inside. The woman is now in a position to force her husband to beg to retrieve it. In 'Der Lohn einer guten Tat' ("Reward for Good Behavior", issue #877, 1862), a man saves a boy from drowning, but is instead forced to pay the city council for his deed. The picture story is accompanied by the line "based on a true story”, leaving modern-day readers wondering whether Busch based it on a personal anecdote. Ancient Greek philosopher Diogenes is the protagonist in 'Diogenes und die bösen Buben von Korinth' ("Diogenes and the Mean Kids from Korinthe", issue #881, 1862), sleeping in his iconic barrel, when two brats bother him. He eventually gives them a dose of their own medicine by rolling his barrel over them, leaving them flat. This may be the first instance in a comic strip where characters are comically flattened like gingerbread men.

In 'Das Teufelswirtshaus', also known as 'Der Hahnenkampf' ("Devil's Tavern", issue #882, 1862), the Devil tries to enter a tavern of debauchery by the chimney, but ends up burning himself. 'Die Rache des Elefanten' ("The Elephant's Revenge", issue #906, 1862) portrays an elephant getting his revenge on an African hunter. In the pantomime comic 'Die gestörte, aber glücklich wieder errungene Nachtruhe' ("The Disturbed, but Luckily Restored Night Rest", issue #912, 1862), a man is bothered by a ticklish cricket at night. Eventually, he manages to capture the insect, burns it with a candle and crawls back between the sheets. Disrupted nights return in 'Ein Abenteuer in der Neujahrsnacht, oder Warum Herr Brandmaier das Punschtrinken für immer verschworen hat' ("A New Year's Night's Adventure, or Why Mr. Brandmaier swore off drinking Punch forever", issue #913, 1863). Mr. Brandmaier arrives home drunk and burns himself on a candle, only to wake up and realize it was all just a dream. Busch was early to observe rats' intelligence in 'Die kluge Ratte' ("The Clever Rat", issue #921, 1863), in which a rat uses its tail to soak up syrup from a barrel hole otherwise too small to stick its snout through. In the adorable pantomime comic 'Der Schnuller' ("The Pacifier", issue #923, 1863), two dogs steal a baby's pacifier and fight over it. When a wasp bothers them, they get distracted. The baby's grandmother eventually kills the insect, takes the pacifier and gives it back to her grandchild.

Busch might be the first comic artist to use an absent-minded professor, namely in 'Der zerstreute Rektor' ("The Absent-Minded Rector", issue #930, 1863), where a professor goes on a trip and is told by his wife to refresh his clothing every few days. When he returns home, he appears to have gained weight, but it turns out he merely forgot to take off his unclean shirts all the time he was away. A bar visitor wonders about the bad taste of his beer in 'Die unangenehme Überraschung' ("The Unpleasant Surprise", issue #931, 1863). It is eventually revealed that a mouse drowned in it, causing him to dash off in disgust. 'Moderne Malerschnaderhüpfeln' ("Modern Painting Toddler", issue #938, 1863) depicts a boy painting his own child-like versions of Greek mythological characters, a cow and a lamb. Complicated love triangles are subject in 'Müller and Schornsteinfeiger' ("Miller and Chimney Sweep", issue #936, 1863), where a miller, chimney sweep, cook and maid all have secret affairs with each other, without their "official" partner knowing about it. It leads to a lot of misunderstandings and jealous fights, until they decide to have an open relationship.

'Eginhard und Emma' was featured in a carnival-themed edition of Die Fliegende Blätter, issue #970. Based on the medieval chivalric romance of the same name, Busch moves the action to his own era. Emperor Charlemagne has a daughter, Emma, who is lovingly abducted by her lover, Eginhard. They are caught, brought back to the emperor, who eventually gives them his blessing. The picture story has some political subtext. Eginhard is reminiscent of Ludwig II, emperor of Bayern, while Charlemagne's servant Frederik is a caricature of Frederick the Great. The work pokes fun at the mythology surrounding the Holy Roman Empire, already promoted by German nationalists when Busch was alive. Here, none of the royal splendor is present. Charlemagne lives in a simple house and is depicted as a rheumatic old man, using a chamber pot at night and wearing clogs. 'Eginhard und Emma' also satirizes Catholicism and governmental bureaucracy.

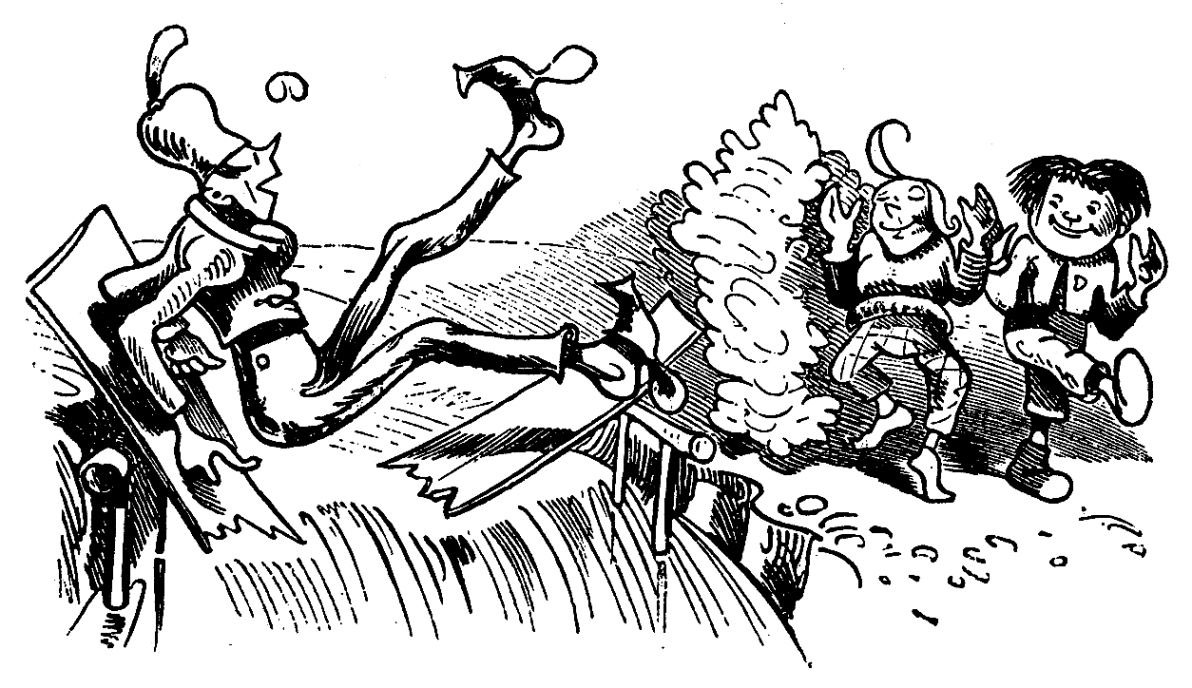

'Der unfreiwillige Spazierritt' (1865).

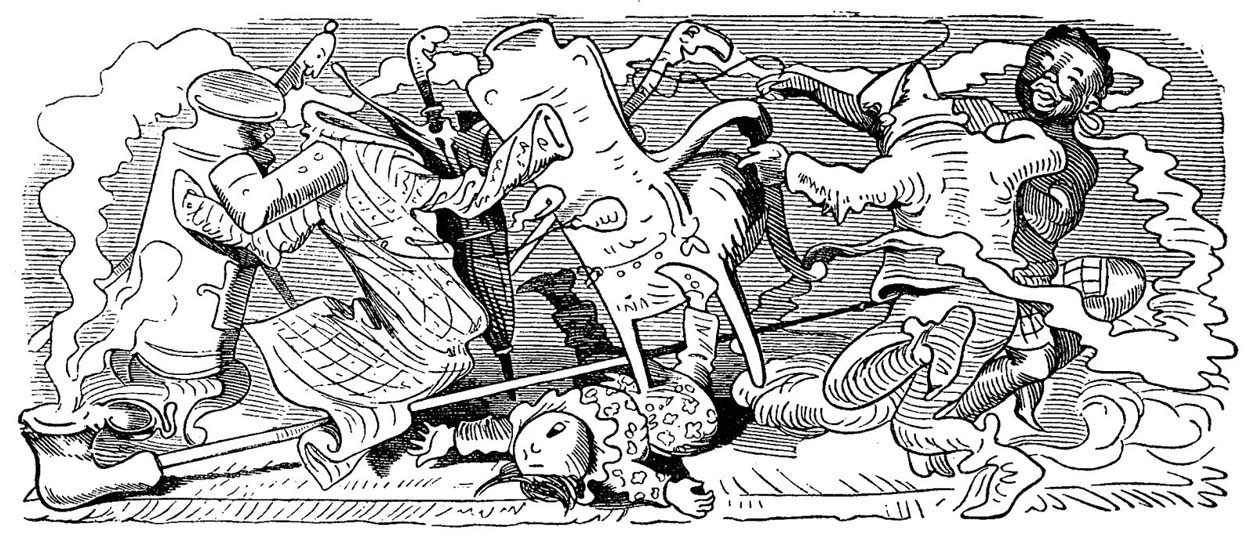

A wackier tale is 'Der unfreiwillige Spazierritt ("The Involuntary Stroll", issue #1026, 1865), in which the corpulent Mr. Pumps goes swimming in a lake. When a mounted lieutenant rides by, Pumps asks him to help him ashore. Still dressed in his swimming pants, Pumps sits on the lieutenant's horse to dry, only for the animal to suddenly run off, with the half nude Pumps still on its back. He embarrasses himself by gallopping past representatives of the Women's institute and the local elementary school. After finally dismounting his noble steed, Pumps rushes into the nearest house, only to be chased out by women who think he's an exhibitionist. Eventually the disgraced gentleman is clothed and brought back home.

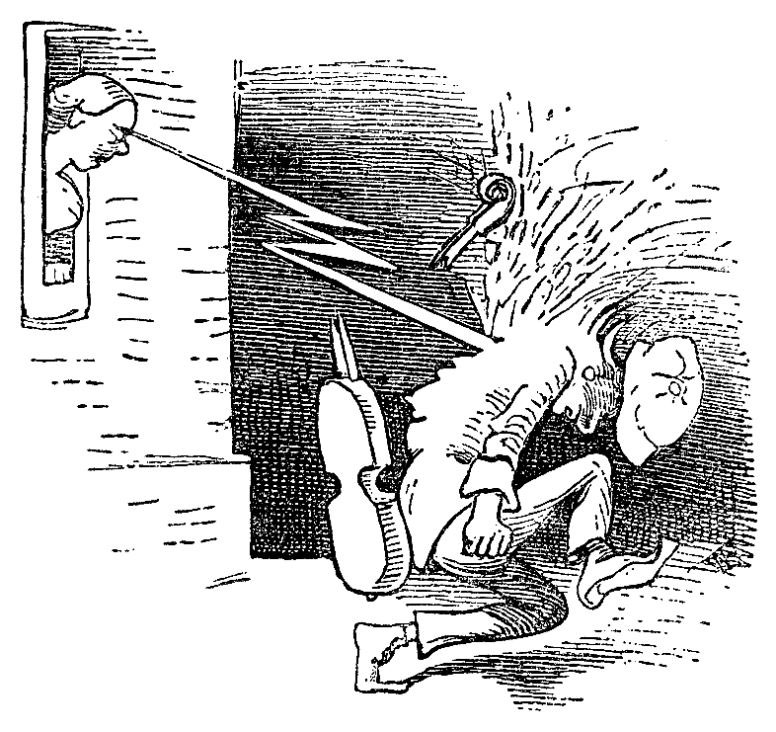

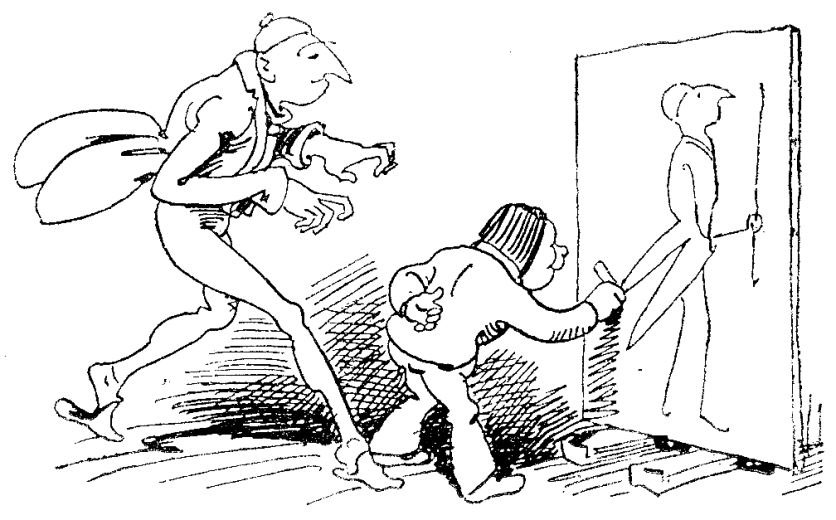

More public embarrassment occurs in 'Ein galantes Abenteuer' ("A Gentle Adventure", issue #1102, 1866), where a gentleman tries to be nice to five cleaning ladies, who misunderstand his good intentions, clobber him with their brooms and then steal the pennies he throws on the ground to distract them. 'Der vergebliche Versuch' ("The Vain Attempt", issue #1121, 1867) differs from most of Busch's other picture stories in the sense that the only narration appears at the start of the tale, as a kind of introduction. The rest of the images form a pantomime comic mocking a drunkard who wants to light his cigar to a candle, but accidentally sets his nose on fire. A pure pantomime comic is 'Das gestörte Rendezvous' ("The Disturbed Rendezvous", issue #1160, 1867), in which a lover uses a huge basket on a string to climb to his girlfriend's balcony, which she pulls up. Her angry father interferes, but after several shenanigans he ends up being more bruised and embarrassed than them. 'Der Katzenjammer am Neujahrsmorgen' ("The New Year's Morning Hangover", issue #1174, 1868) is an accurate visualization of what a hangover feels like. Busch uses interesting imagery to imply the headache, like black bubbles and a little devil spinning a wheel next to the protagonist's head. The title may also have inspired Rudolph Dirks in 1897 to the title of his Busch-esque newspaper comic 'Der Katzenjammer Kids'.

'Der Katzenjammer am Neujahrsmorgen' ("The New Year's Morning Hangover", 1868).

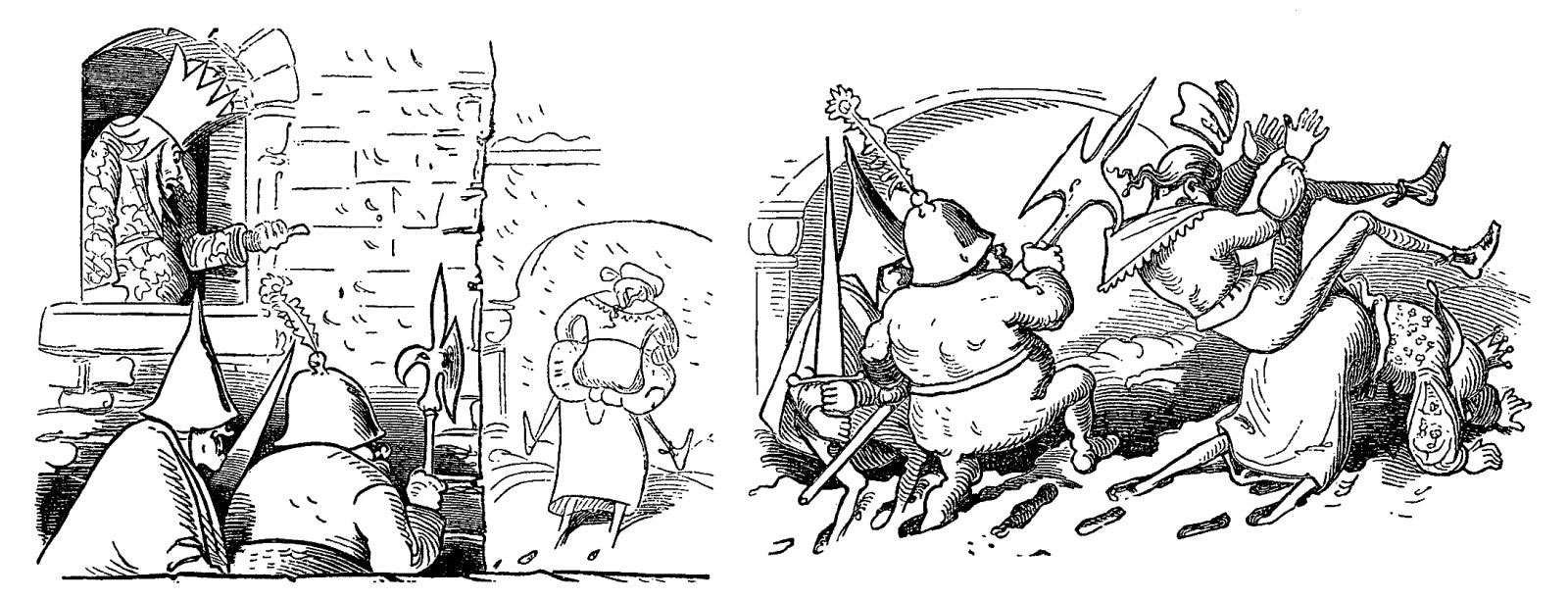

In 'Der schöne Ritter' ("The Handsome Knight", issue #1181, 1868), a man finds out that wearing a knight's outfit is very impractical when going to a bar, or trying to sleep in his bed. With 'Der Partikularist' ("The Particularist", issue #1324, 1870), Busch commented on the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871). A German sympathizes with the French army and cheers whenever they are victorious. When the Prussians win, he gradually transforms into a donkey. Another satirical look at the changing times is 'Ehre dem Photographen! Denn er kann nichts dafür!' ("Honor the Photographer! It's Not His Fault", issue #1336, 1871), in which Busch mocks the new artform of photography, particularly its inability to capture people who don't sit still in front of the camera. Several panels visualize photographic mistakes by showing overlapping images of the same people. Busch's final story for Die Fliegende Blätter, 'Der hastige Rausch' ("The Hastily Rush", issue #1346, 1871), features a drunk restaurant visitor being thrown out for harassing the waitress and another customer.

'Die kleinen Honigdiebe' ("The Little Honey Thieves", 1859).

Pictures stories for the Münchener Bilderbogen

Busch also made various one-shot picture stories for the Münchener Bilderbogen prints by Braun & Schneider. Since the invention of printing, several European countries had a long tradition of picture story prints, meant for the entertainment and education of the poorer parts of society. In France, the so-called Épinal prints presented idealized depictions of historical events and "true stories". In the Dutch speaking parts of the Low Countries, these prints reflected the religious, ethical, social and pedagogical views of their time. The Germans called them "Bilderbogen". Known as catchpenny prints, children's prints, folk prints or "little lad's papers" ("mannekensbladen"), they were mass-produced, often on cheap paper, with rudimentary artwork and text captions with simple rhymes. The woodcut "Bilderbogen" by Braun & Schneider however had high quality artwork, created by popular artists, including Wilhelm Busch.

'Die kleinen Honigdiebe' ("The Little Honey Thieves", sheet #242, 1859) is a moralistic text comic about two boys who try to steal honey from their neighbor's beehive, but get stung. In an imaginative sequence, their noses are so swollen up that they are bigger than their own heads, leaving them unable to eat. A blacksmith has to pull the stingers out with a shrew. The story was inspired by Busch's maternal uncle, Georg Kleine, who was a priest and a beekeeper. In fact, during his wandering student years, Busch once considered moving to Brazil to become a beekeeper. In 'Der kleine Maler mit der grossen Mappe' ("The Little Painter with the Huge Wallet", sheet #248, 1859), the reader follows a short-sized painter using a ridiculously large wallet as a smoke screen, rain screen, raft, sled, umbrella and a glider. A boy named Pepi is our unlucky hero in 'Der kleine Pepi mit der neuen Hose' ("Little Pepi's New Trousers", sheet #286, 1860), where the little kid ruins his expensive new pair of pants by respectively falling into a river, getting stuck to a gooey substance in a shoe salesman's store and later tumbling into a vat with syrup. His father pulls his ear (comically extending it) and later canes him.

'Der kleine Pepi mit der neuen Hose' ("Little Pepi's New Trousers", 1860).

Two mischievous boys want to rob a raven's nest in 'Das Rabennest' ("The Raven's Nest", sheet #308, 1861), but fall from the tree into a puddle, leaving them as black as ravens. Another naughty kid bothering birds appears in 'Der hinterlistige Heinrich' ("Crooked Heinrich", sheet #361, 1864), in which little Heinrich uses a pretzel to capture a little goose, but its parents pick up the brat and drop him in the chimney of his house, where the kid plummets into his mother's cauldron. A monkey gets his revenge on a taunting boy in 'Der Affe und der Schusterjunge' ("The Monkey and the Shoemaker's Boy", sheet #361, 1864). Winter hijinks occur in 'Die Rutschpartie' ("The Downhill Slide", sheet # 370, 1864), where a sledder accidentally kicks over various people on his way down. A gag that has often been repeated in many humor comics since.

'Die Rutschpartie' ("The Downhill Slide", 1864).

A young woman in a crinoline dress is ambushed by various animals in 'Adelens Spaziergang' ("Adelens Stroll", sheet #376, 1864), until a stork picks up her crinoline to make a nest. More animal mischief occurs in 'Der gewandte, kunstreiche Barbier und sein Kluger Hund' ("The Skillful, Artistic Barber and his Clever Dog", sheet #399, 1865), in which an incompetent barber accidentally cuts off his client's nose, which his dog tries to eat. Luckily, the inventive hairdresser is able to stitch the organ back on. Busch shows off his expertise as a visual storyteller in the pantomime comic 'Das warme Bad ("The Warm Bath", sheet #412, 1866), where a dog owner and his pet take a hot bath, hiding most action behind a discretion sheet. Basically a charming atmospheric tale, the artist implies a lot while not showing much.

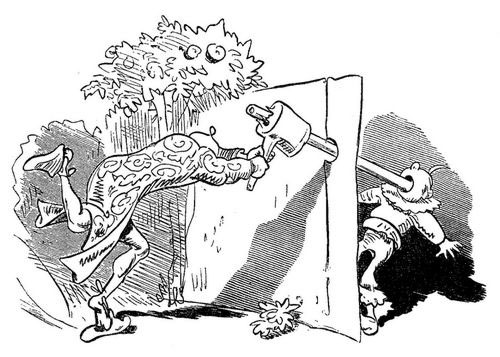

With 'Zwei Diebe' ("Two Thieves", sheet #427-428, 1866), Busch drew a more serious picture story about two burglars who try to rob a privateer and his wife, but eventually receive their retribution when they escape through the window and are pierced by the umbrellas they used to soften their fall. The scenes in which the criminals rob the couple are disturbing and genuinely menacing. 'Der neidische Handwerksbursch' ("The Jealous Craftsman", sheet #436, 1867) contrast the life of a poor, starved craftsman and an obese man who enjoys three meals in a restaurant. While the corpulent restaurant customer appears to be the lucky one, the craftsman is at least free to roam the Earth, while the obese man is revealed to have problems of his own, namely a bandaged leg. Busch provided his own adaptation of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's comical opera 'Die Entführung aus dem Serail' ("The Abduction from the Seraglio", sheet #439, 1867), in which a handsome knight saves a young woman from the sultan's harem.

In 'Die feindlichen Nachbarn oder die Folgen der Musik' ("The Villainous Neighbors, or Musical Consequences", sheet #443, 1867), Busch pioneers an often reused visual comedy idea. In this picture story, a painter and musician each live in a bordering room. The painter is irritated by the noise and lets water seep inside the musician's room, which leads to a fight, eventually leaving both their rooms in a complete mess. Busch depicts the musician's room in the left panel and the painter's studio in the right, allowing the reader to observe the characters' reactions and interactions at the exact same time. Many humorists have used this method of contrasting two characters' actions in opposing rooms, particularly in comics.

A mean youngster takes a ride on a donkey in 'Vetter Franz auf dem Esel' ("Cousin Franz on a Donkey", sheet #472, 1868), but the animal drives off with him, trashing him against a group of dining people. The fairy tale 'Die Verwandlung' ("The Metamorphosis", sheet #474, 1868) stars a gluttonous boy, Karl, being lured off by a witch, who captures him with a sausage on a fishing rod and then transforms him into a pig. Just when she and her husband will devour him, Karl's sister Ännchen comes to the rescue carrying a magical flower. The witch's husband is burned alive, while his knife accidentally kills her. All ends well when Ännchen transforms Karl back to a human. Good also triumphs over evil in 'Schmied und Teufel' ("Blacksmith and Devil", sheet #455, 1869), where a blacksmith outsmarts the Devil. A well-staged farce by Busch is 'Die Brille' ("The Glasses", sheet #527-528, 1870), where a man refuses to eat his soup after discovering a hair in it. Instead, he wants to drink rum, but his wife snatches the bottle away. A fight erupts, in which she steals his glasses, leaving him unable to see what he's bumping into. Eventually he gives in and the couple make up, while their dog has already gobbled up the rest of their evening meal.

In 'Das Napoleonspiel' ("The Napoleon Game", sheet #543, 1871), a little boy plays Napoleon, while his friends play the army that eventually defeats the Corsican emperor. As can be expected, the kid ends up being so battered and humiliated that he vows to "never play Napoleon again". Busch may be the very first comic artist to portray and ridicule bodybuilding. In 'Die Folgen der Kraft' ("The Consequences of Power", sheet #549, 1871), a man trains his muscles, but his weight-lifting objects eventually cause him to crash through the floor, on top of a couple who were just having dinner.

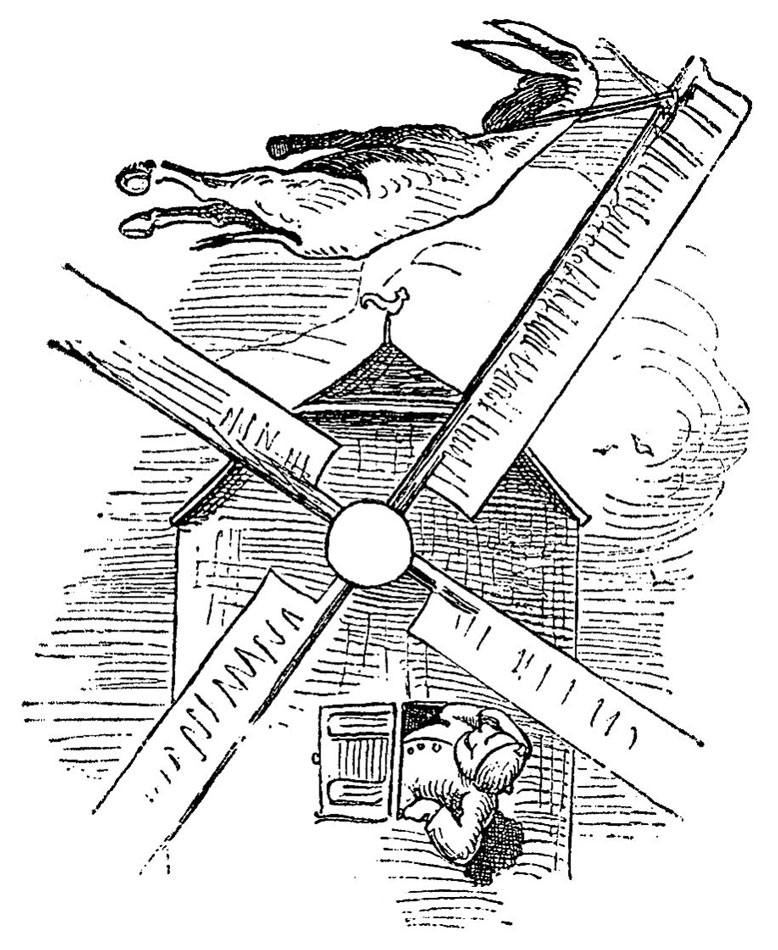

'Der Bauer und der Müller' ("The Farmer and the Miller", 1861).

Most of Busch's picture stories for the Münchener Bilderbogen were one-shots. In only a couple of stories he used recurring characters. An unnamed farmer and his animals are the protagonists in three successive picture stories. However, only his profession shows any continuity. His physical appearance differs in each tale, suggesting he is not the same character. In 'Der Bauer und der Müller' ("The Farmer and the Miller", sheets #300-301, 1861), the farmer ties his mule to a windmill. The miller puts the mill into motion, sending the animal into a spin, eventually killing him. The disgruntled farmer takes the carcass home, gets into an argument with his wife and takes revenge on the miller by sawing the entire windmill down. Busch returned to farmer antics with 'Der Bauer und sein Schwein' ("The Farmer and his Pig", sheets #316-317, 1862), in which a farmer takes his pig to a tavern, where the swine thrashes the place until he's captured and slaughtered. The final farmer story is 'Der Bauer und das Kalb' ("The Farmer and the Calf", sheet #342, 1863), where he tries to lead a stubborn calf to the city. The animal, however, doesn't want to come along. Eventually, the farmer ties a bell around the beast's neck "so he'll think he's a cow". Amazingly, the ploy works.

'Die Strafe der Faulheit' ("The Punishment for Laziness", 1866).

In two other stories, a dogcatcher is a recurring antagonist. In 'Die Strafe der Faulheit' ("The Punishment for Laziness", sheet #431, 1866), Mrs. Ammer's overly cuddled pet Schnick is captured by a dog catcher in front of her own eyes. Since Shnick is so overfed, he can't run away. The dog catcher takes the dog home, slaughters and roasts him for supper. Yet he is "kind" enough to sell the little dog's skin to Mrs. Ammer "for only two cents". At home, she turns her late pet into a taxidermic toy. A follow-up story, 'Der Lohn des Fleisses' ("The Reward of Diligence", sheet #432, 1866), stars a poodle who is disciplined to exhaustion by his owner, not understanding why all these lessons are necessary. He receives his answer when the cruel dogcatcher from the previous story reappears. Contrary to Shnick, the poodle is able to defend himself and is fit enough to escape. His owner is so certain that his pet will return alive that he doesn't even help him. From this perspective, both stories can be considered directly related to one another, as 'Die Strafe der Faulheit' shows how a dog should not be trained, while 'Der Lohn des Fleisses' offers the proper way.

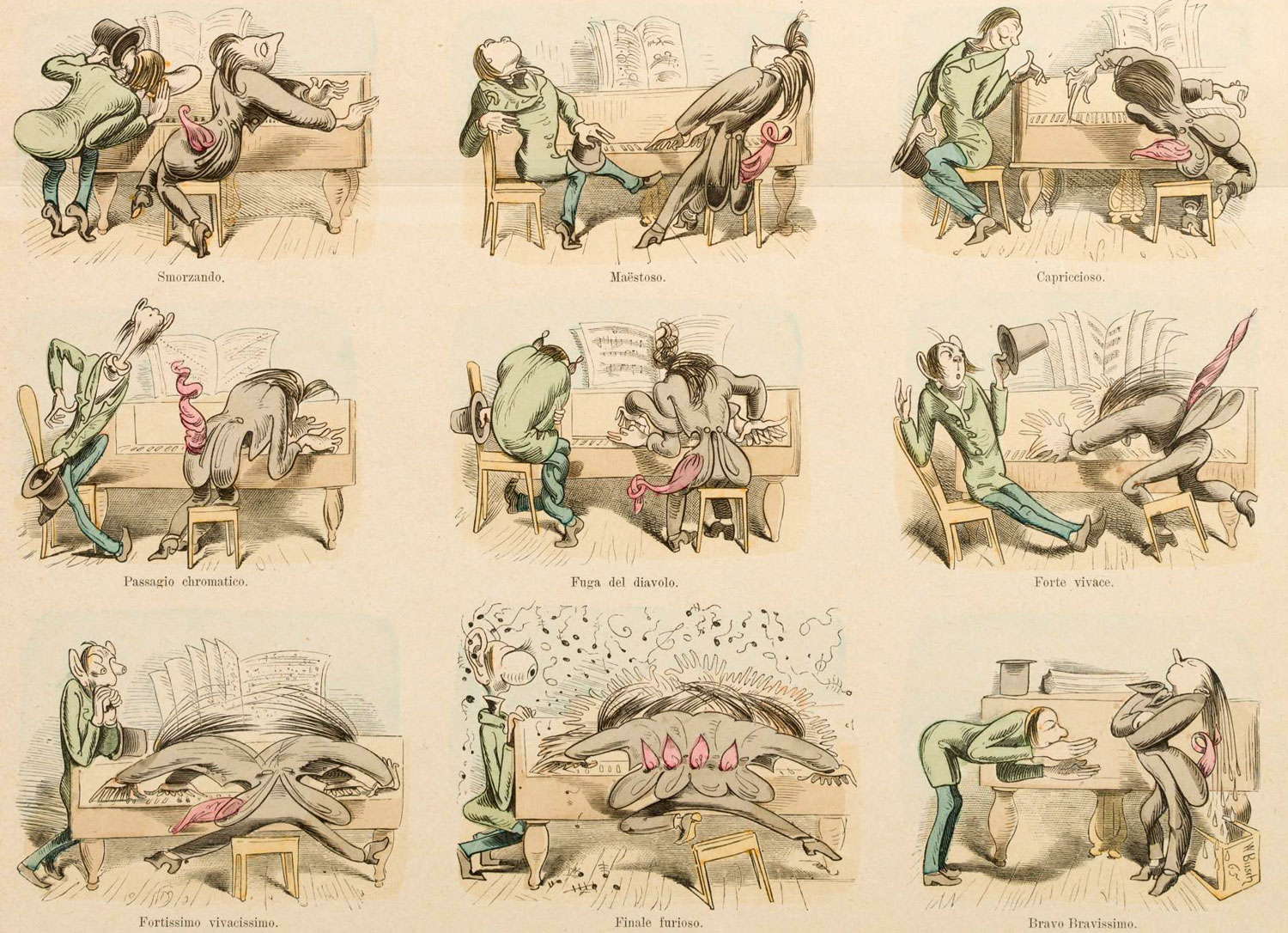

'Der Virtuos' ("The Virtuoso", Münchener Bilderbogen #465, 1865).

Der Virtuos

One of Busch's earliest and most celebrated comics is 'Ein Neujarhskonzert' ("New Year's Concert"), nowadays better known as 'Der Virtuos' ("The Virtuoso", Münchener Bilderbogen #465, 1865). The 15-panel comic depicts a pianist who demonstrates his skills to an impressed listener. Everything is visualized in pantomime, except for the musical terms appearing underneath each image. Busch comically exaggerates the pianist's dramatic poses and wild movements. The musician's fingers go so fast that he appears to have multiple hands. His slick long hair swings and curls back and forth. A handkerchief in his pocket takes a life of its own, dancing along to the music. Musical notes literally fall on the ground, while score sheets float away. As the piece reaches a climax, the pianist is a whirlwind of movement, with sweat afterwards dripping down from his locks. Busch also pokes fun at the attentive listener. During the piece, the listener is able to stretch and enlarge his ears and eyes. In some panels they are bigger than his head. Busch even pioneers the first instance of an "eye-popping take" in a comic. In general, 'Der Virtuos' is Busch's most "cartoony" comic strip, with characters disobeying the laws of physics and logic. Even today, it hasn't lost its humorous power, and remains a witty satire of the theatricality and high-energy performances of classical musicians. In the 1920s, German futurist painter August Macke regarded Wilhelm Busch as a predecessor to his artistic movement, since he already visualized motion in images.

Bilderpossen - 'Hansel und Gretel' (1864).

Bilderpossen

Wilhelm Busch's (often self-illustrated) stories for Fliegende Blätter and Münchener Bilderbogen, both published by Kasper Braun, were well-received and kept him financially stable during sour times. But they remained his only reliable source of income, as his paintings didn't sell. The operettas and operas he wrote librettos for flopped and no publisher was interested in his self-researched folkloric tales. Busch didn't like the idea of being completely dependent on just one person and found an additional publisher in Heinrich Richter. Richter was sceptical and critical about a proposed manuscript by Busch, but eventually greenlighted it. In 1864, it appeared on the market under the title 'Bilderpossen', marking Busch's first book publication.

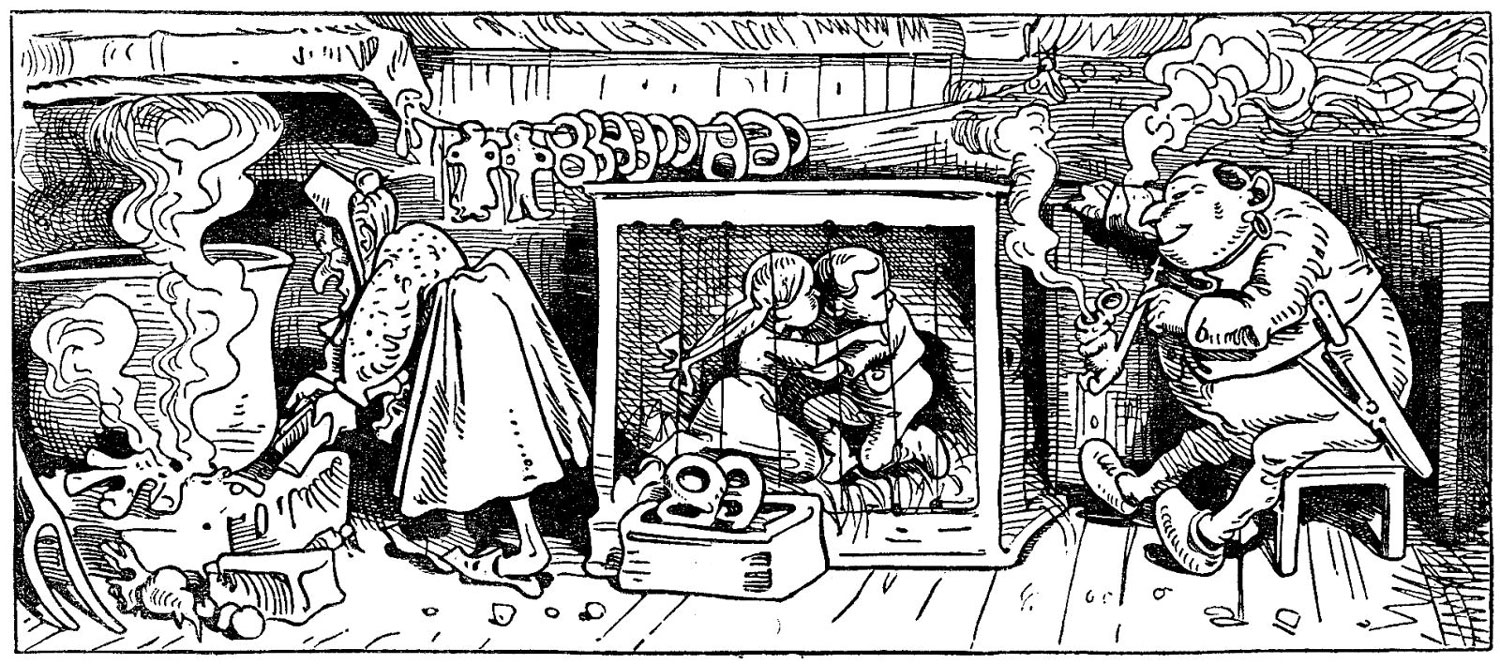

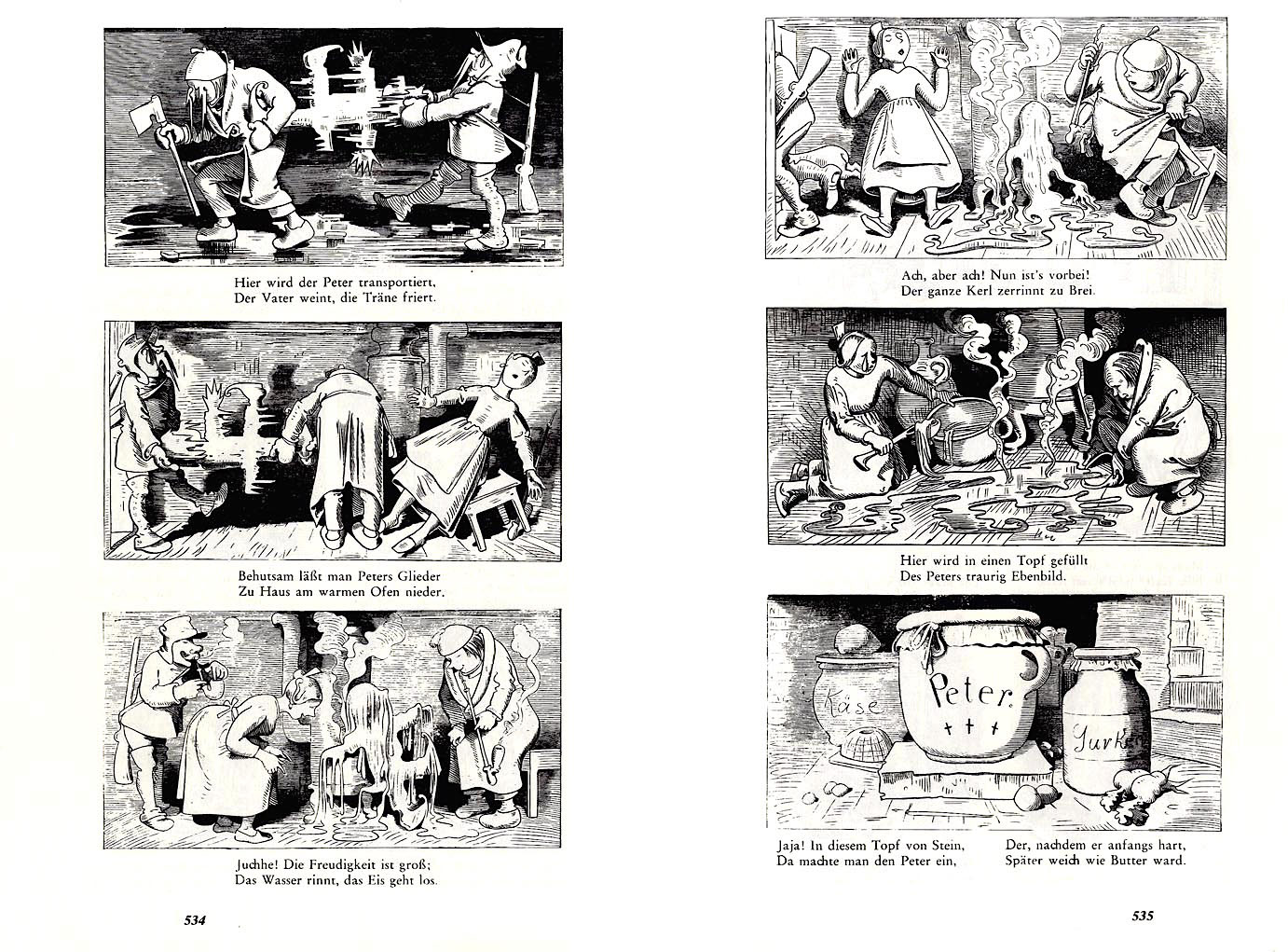

Bilderpossen - 'Eispeter' (1864).

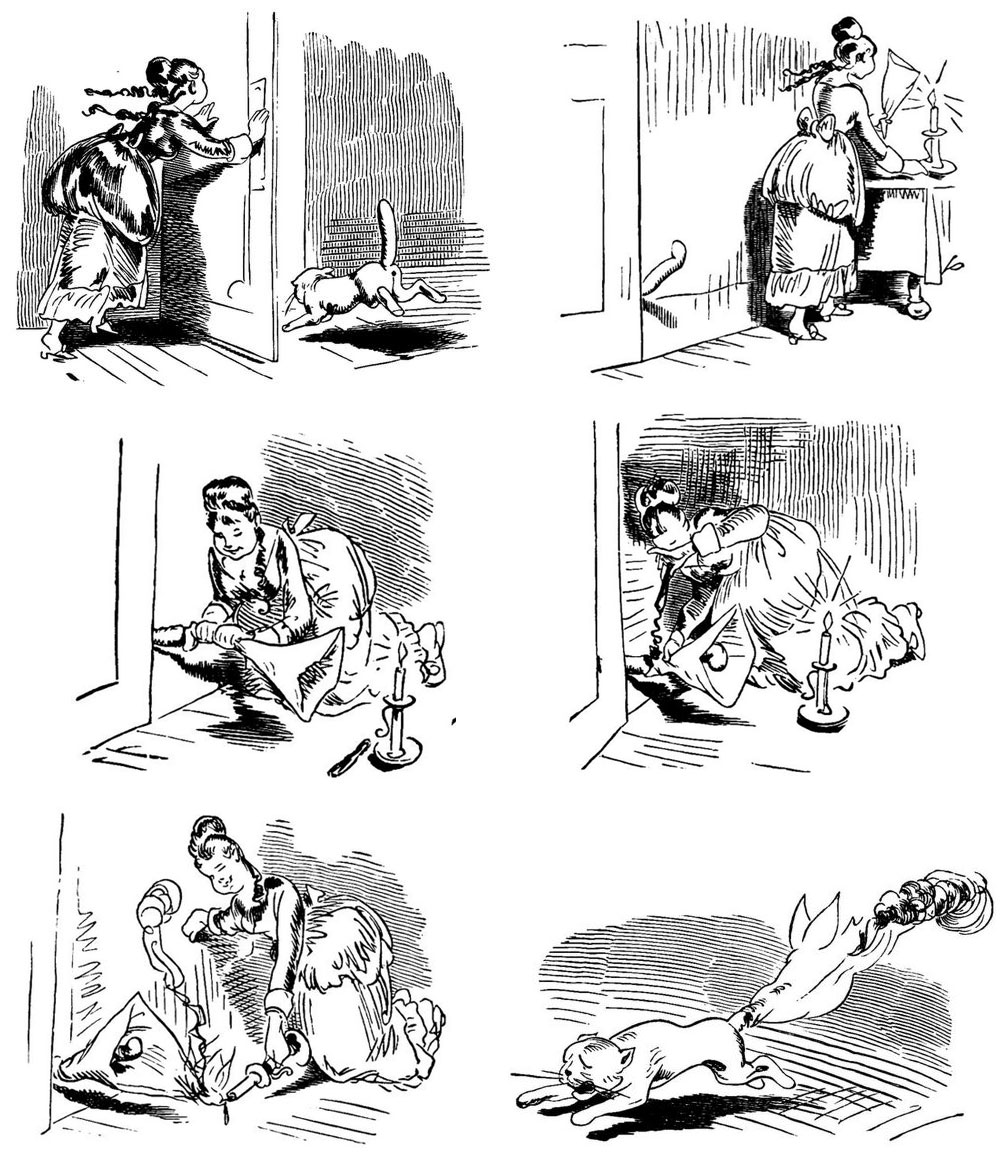

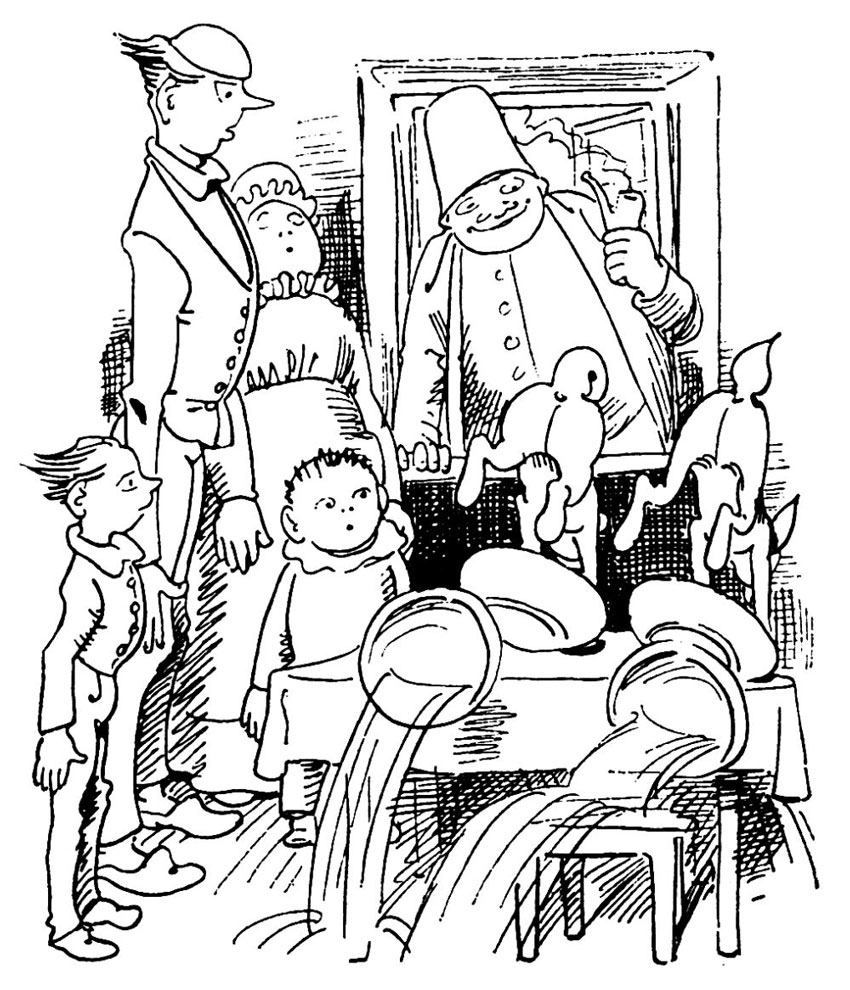

The collection contains four separate tales, all presented in text comic format, with text captions underneath the images. 'Hansel und Gretel' is a parody of the famous fairy tale, in which the children get lost in the woods because they hate their mother. The witch turns out to be married to a cannibal. In 1862, Busch had already spoofed this fairy tale, but then as a musical play for composer George Kremplsetzer. In 'Katze und Maus', a cat tries to catch a mouse but only causes a lot of mayhem in the household. In the end, the mice celebrate their victory by dancing in a circle. A moralistic tale is 'Krischan mit der Piepe' , in which a young boy smokes his father's pipe, but predictably turns sick. Busch elevates the "scare 'em straight" factor by letting the nauseous kid see all kinds of frightening hallucinations, making modern-day readers wonder if there was more in that pipe than tobacco alone. The most disturbing story is 'Eispeter'. A boy called Peter goes ice skating, ignoring warnings from adults. He crashes through the ice and gets frozen. At first, the situation looks comical, with his father and uncle taking their little frozen relative home to thaw him. But the heat works a little too well and the poor boy melts away. His remains are then scooped and kept in a weck jar.

Bilderpossen - 'Krischan mit der Piepe' (1864).

Unfortunately, Richter's hunch turned out to be correct, as 'Bilderpossen' didn't sell. Readers didn't know whether it was intended for children or adults. Particularly 'Eispeter' was considered too horrific, on the level of Heinrich Hoffmann's similarly nightmarish "educational" 1845 picture book 'Der Struwwelpeter'. In 1960-1961, when 'Bilderpossen' was reprinted in East Germany, 'Eispeter' was completely omitted.

'Max und Moritz' - 'Letzter Streich' (1865).

Max und Moritz

After Busch's first book, 'Bilderpossen' (1864), had flopped, he left publisher Heinrich Richter and returned to his previous publisher, Kasper Braun. While Busch had already prepared a new picture story, he had lost all faith in it. He decided to sell the manuscript and its rights to Braun, in exchange for a hefty sum. Braun paid Busch the same amount of cash a writer would have received for two years worth of publications. His only request was that Busch would revise the text and artwork, which he did, on woodblocks. In late October 1865, the story, 'Max und Moritz - Eine Bubengeschichte in sieben Streichen' (1865) was published as a children's book by Braun's company Braun & Schneider. The story is presented as a text comic, with text on rhyme underneath the images. The black-haired boy Max and blond-haired Moritz (who has a cow lick quiff) are sneaky tricksters. In seven tales, they play pranks on their environment.

Busch had used a mischievous boy before in picture stories for Fliegende Blätter, such as 'Tandelnswerte Antwort auf eine wohlgemeinte Frage' ("Reprehensible Answer to a Well-Intentioned Question", 1860) and 'Trauriges Resultat einer vernachlässigten Erziehung' ("The Sad Result of a Neglected Education", 1860). The latter tale already introduced a tailor named Böck, similar to the one used in 'Max und Moritz'. A naughty boy can also be found in 'Der hinterlistige Heinrich' ("Crooked Heinrich", 1864) and 'Der Affe und der Schusterjunge' ("The Monkey and the Shoemaker's Boy", 1864) in Münchener Bilderbogen. Similarly, Busch used two boys playing pranks on their environment in 'Die kleine Honigdiebe' ("The Little Honey Thieves", 1859) and 'Das Rabennest' ("The Raven's Nest", 1861), both published in Münchener Bilderbogen, and 'Diogenes und die bösen Buben von Korinth' ("Diogenes and the Mean Kids from Korinthe", 1862) in Fliegende Blätter. Even after 'Max und Moritz', Busch re-used bad little boys in picture stories like 'Das Pusterohr' ("The Beanshooter", Über Land und Meer, 1867), 'Der Wurstdieb' ("The Sausage Thief", Daheim, 1868) and 'Plisch und Plum' (1882).

In their first story, Max and Moritz sprinkle crusts of bread for the chickens and rooster of widow Bolte, but attach them to a string. As the dumb birds gobble up the bread, they are suddenly attached to each other and get wired in a tree. Now all dead, Mrs. Bolte decides to roast the birds, but the mean boys pull the delicious food from the cauldron through the chimney by using a stringed hook. Their next victim is Böck the tailor. The little brats saw the legs of a wooden bridge in half and yell insults at Böck. When the angered draftsman rushes out, he crosses the bridge, which collapses and plummets him into the river. Since teachers are school boys' natural enemies, Max and Moritz also target their headmaster Lämpel. They break inside his house and stuff his pipe with gunpowder. When he lights it, it explodes, leaving him with severe burn wounds. Even the boy's own relatives aren't safe: they fill their uncle's bedroom with maybugs, giving him a long, sleepless night to crush all the invertebrate intruders. Max and Moritz' luck turns when they try to steal pretzels from a baker. They fall into a vat of dough, while the baker puts them in the oven. The devious juvenile delinquents eat themselves through the dough and escape. At farmer Mecke's barn, they cut holes in his bags of grain, until they are caught, brought to the mill and grinded flat (!), while ducks eat their remains. At this point, the little brats are so hated by the villagers that nobody cares that the miller basically just murdered two children. Instead everybody revels: "Gott sei Dank! Nun ist's vorbei mit der Übeltäterei" ("God be praised, now the evil has passed"), which has become a well-known line in German literature and everyday language.

'Max und Moritz' is a very sadistic tale, brimful with black comedy culminating in a disturbing ending. Though in terms of content, it's actually not that different from other 19th-century moralistic children's tales, including Heinrich Hoffmann's nightmarish book 'Der Struwwelpeter'. Several of Busch's biographers have investigated whether 'Max und Moritz' was autobiographical. The scene in which the two boys stuff their teacher's pipe with gunpowder was partially inspired by a real-life trick Busch pulled off as a child. He once put cow hairs in the pipe of a mentally disabled man, but was caught and punished by his uncle. Some of the tricks in 'Max und Moritz' also share similarities with tales about the German folklore trickster Till Eulenspiegel.

Max und Moritz: success and cultural legacy

'Max und Moritz' takes a significant place in the history of comics. It's a perfect combination of text and imagery, built around two strong, colorful characters and well-staged gags. Busch uses self-invented onomatopoeia, including "Schupdiwup" (to imply a fishing rod hailing in a fried chicken), "Knusper Knasper" (when the boys bite through a bread crust), "Ritzeratze" (for the breaking bridge) and "Rickeracke" (when the mill grinds). While the onomatopoeia aren't included in the illustrations yet, they do appear in the accompanying text. Several scenes are very reminiscent of classic comic strip gags, like the exploding pipe which leaves the victim with a black, ash-burned face.

'Max und Moritz' was a slow-burner, but eventually became the hit Busch had been waiting for. Book compilations became bestsellers all over the German-language world. Two lines from the story, "Die grösste Freud ist doch die Zufriedenheit" ("The greatest virtue is satisfaction”) and "All mein Hoffen, all mein Sehnen" ("All my hope, all my longing") have become common expressions in everyday German language. 'Max und Moritz' was also translated into English, Dutch, Danish, French, Polish, Russian, Hungarian, Swedish and Hebrew. In 1887, it was even the first Western children's book to be translated into Japanese. The Belgian jesuit monk Jean-Guillaume Levaux published a version in the dialect of his home city Liège, 'Li Vicarèie di Simon en Linâ Mèttowe ès Ligwet' (1889), though removing any reference to the Church or religion. The very concept of children playing tricks on adults inspired a tidal wave of similar gag comics, though, contrary to 'Max und Moritz', more as one-page gags than long stories. Already by the end of the 19th-century, several German-language authors produced unofficial sequels, becoming a genre of its own, nicknamed "Moritziade". When in the USA Rudolph Dirks launched his classic newspaper gag comic 'Der Katzenjammer Kids', the designs and personalities of his protagonists Hans and Fritz were directly modelled after 'Max und Moritz'.

As popular as 'Max und Moritz' was with readers, the "serious" literary world regarded it as infantile pulp, setting a bad example to children. Since it was a picture story, it didn't challenge boys and girls to read a "proper" text, indeed the first time in history that comics received this eternal stigma. The images in 'Max und Moritz' tingled children's imagination more directly than a narrated or straightforward written story. Since Max and Moritz commit most of their mean pranks to simply laugh at other people's misery, moral guardians feared that the book would inspire copycat behavior. Even decades later, in 1929, a school official in the Austrian region of Styria prohibited sales of 'Max und Moritz' to people under 18 years old. Oddly enough, critics didn't seem to notice that Max and Moritz are eventually punished for their bad behavior by dying a gruesome death. And while the duo is mean, the adults' disproportionate retribution for their "crimes" really doesn't make them more morally correct.

Whatever the case, 'Max und Moritz' have outlasted their critics and became a classic of German literature. In 1949, the book was adapted into a ballet, composed by Richard Mohaupt, with choreography by Alfredo Bortoluzzi. Günther Kretzschmar made the school cantata 'Max und Moritz' (1963), which has been staged in many German schools. There have been additional musical stage plays and instrumental compositions, composed respectively by Gisbert Näther, Jan Koetsier (1994), Samuel Adler (2000) and Martin Bärenz (2008). In 1923, Curt Wolfram Kieslich made the first film adaptation of 'Max und Moritz', a silent animated short. The Diehl Brothers directed a stop-motion animated feature, 'Spuk mit Max und Moritz' (1951), Norbert Schultze the live-action children's film 'Max und Moritz' (1956), while in 1978 Studio Hamburg produced two animated TV specials, directed by Herman Leitner and narrated by Heinz Rühmann. Two animators who worked on the 1978 special were John Halas (of Halas & Batchelor fame) and Harold Whitaker. In 1999, 'Max und Moritz' was also adapted into an animated TV series. A remarkable fact about this latter TV show is that it uses new and different shenanigans for Busch's iconic duo and kills them off at the end of each episode. But in the next one, they are back alive and ready for more mischief.

German painter Johannes Grützke made the painting 'Moritz' (1960), depicting three grinning children holding chickens. Jörg Michael Günther wrote a tongue-in-cheek reflection on Max und Moritz in his book 'Der Fall Max und Moritz' (Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main, 1988), discussing what the real-life legal ramifications would have been if there had been a court case against the boys. The famous brats were also satirized by Thomas Frydetzki and Annette Stefan in the black, politically incorrect and subversive comedy film 'Max und Moritz Reloaded' (2005), portraying the duo as modern-day teen juvenile delinquents sent to a boot camp to correct their behavior. The protagonists in the Netflix series 'The Defeated' (2021) are also nicknamed "Max" and "Moritz" and Busch's book is featured as the direct inspiration for their names.

The cultural impact of Busch's bad boys goes even further. After losing the First World War, Germany had to pay off the neighboring countries' war debts, plunging the country into bankruptcy. The government issued various emergency money notes, some of which were made more attractive by the company Gatersleben by printing 'Max und Moritz' imagery on them. During the Second World War, two German military car types in North Africa and self-propelled guns at the Eastern Front had the names "Max" and "Moritz" painted on the side of them. Since 1984, the bi-annual Max-und-Moritz Preis has been handed out to honor young comic artists. In 2018, the Dutch theme park De Efteling introduced a rollercoaster ride named after 'Max und Moritz', in line with park designer Anton Pieck's love for 19th-century life and culture. The boys also have their own statue in the German town of Mechtshausen.

'Max und Moritz' also acquired some notable celebrity fans. The Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud kept a 'Max und Moritz' book in the waiting room of his office. In a letter posted to his Hungarian colleague Sandor Ferenczi, Freud compared Alfred Adler and Wilhelm Stekel, editors of the magazine Centralblatt, to Max and Moritz, since they annoyed him. Busch wasn't the only comic artist who fascinated Freud and Ferenczi: they also had attention for a comic by Nándor Honti, AKA Bit. 'Max und Moritz' were additionally praised by German emperor Wilhelm II, who had read the books when he was a boy. He celebrated the stories as "exquisite works full of genuine humor", which he predicted would "last forever". At Busch's 70th anniversary, Wilhelm II sent him a congratulatory telegram. Another icon of the First World War, infamous German aviator Manfred von Richthofen, better known as "The Red Baron", had two dogs named Max and Moritz.

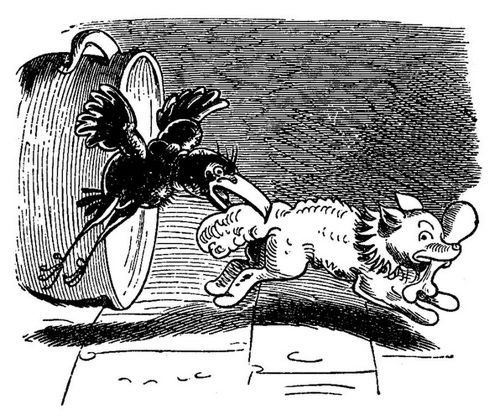

'Hans Huckebein der Unglücksrabe' (1867).

Hans Huckebein

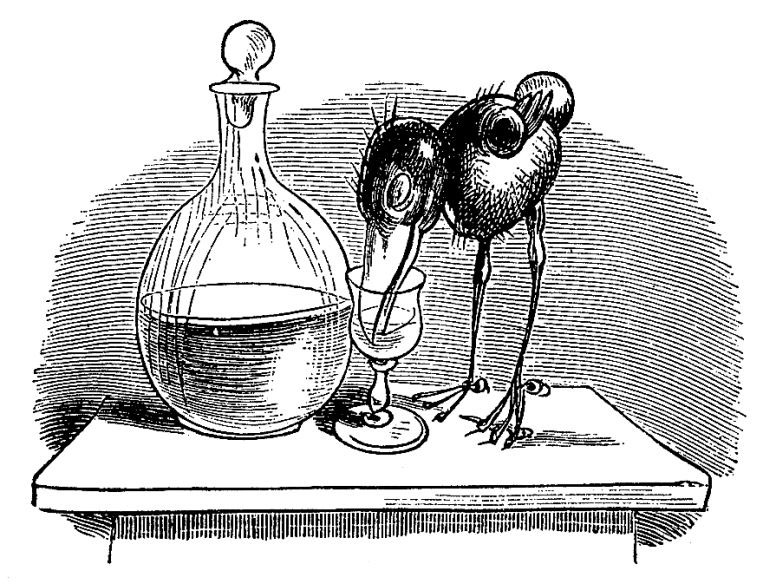

Another famous picture story by Wilhelm Busch, 'Hans Huckebein der Unglücksrabe', was serialized between October 1867 and September 1868 in the newspaper Über Land und Meer, which circulated in Stuttgart. The text comic centers on the raven Hans Huckebein, who is adopted by a boy named Fritz. The bird turns out to be a bad pet, biting people, stealing food and knocking over various household objects. The ill-mannered raven eventually drinks a glass of liquor, gets drunk and finds itself entangled in Fritz's aunt's knitting gear. The bird then accidentally strangles himself, dying a moralistic death. The story was inspired by Busch's brother from the town of Wolfenbüttel. He once told him that a gardener's pet raven had killed all the chicks on his farm by pecking the birds on their heads when they wanted to drink from the water bowl.

'Hans Huckebein der Unglücksrabe' (1867).

Like 'Max und Moritz', 'Hans Huckebein' had a considerable impact on German society. His name inspired a kindergarten in Berlin, which used a raven as its symbol. In 1924, Curt Wolfram Kiesslich adapted the story into a feature film. Walt Disney based the design of the raven of the Evil Queen in 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs' (1937) on Hans Huckebein. During World War II, a proposed (but never built) Focke-Wulf Ta 183 jet fighter was to be named Hans Huckebein. The character of Knickebein the raven in Rolf Kauka's comics was also inspired by Busch's bird. Since 2006, the raven's name also lives on in the literary award the Hans Huckebein Award.

'Das Pusterohr' ("The Beanshooter").

Additional picture stories

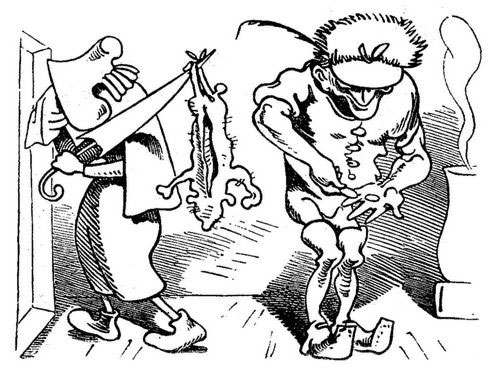

While 'Hans Huckebein' is Busch's most enduring picture story from the Stuttgart magazine Über Land und Meer, he also created several more one-shot picture stories for the title, serialized between October 1867 and September 1868. In 'Das Pusterohr' ("The Beanshooter") a man named Bartelmann is bothered by a little boy blowing pebbles at him through a hollow pipe sticking through a hole in his fence. He gets his revenge by hammering the pipe back in, smashing the boy's teeth. 'Die kühne Müllerstochter' ("The Brave Miller's Daighter") depicts a miller's daughter fending off a group of burglars. In 'Das Bad am Samstagabend' two little brothers start a fight in the bathtub, while in 'Der Schreihals' ("The Crybaby") nobody can figure out why their little baby won't stop screaming, until grandmother discovers the reason: a pair of scissors was stuck in its diaper.

Busch also made a one-shot picture story for the magazine Daheim, 'Der Wurstdieb' ("The Sausage Thief", 1868), in which a little boy named Hans tries to steal a sausage, but a dog grabs it away and forces the boy to stand all night in front of his dog house. The next morning, Hans is frozen into a block of ice. When the neighbor spots the kid, he takes the frozen boy inside, but trips, causing Hans to shatter into a million pieces. Busch's 'Die Prise' ("The Pinch", 1872) appeared in Die illustrierte Welt and portrayed a man having difficulty using a box of snuff. A story of an unknown date and publication is 'Auch der erledigt italienische Frage' ("This solves the Italian question"), in which an Italian removes a pebble from his shoe.

'Monsieur Jacques à Paris während der Belagerung von 1870' ("Monsieur Jacques from Paris during the 1870 Siege of Paris").

Monsieur Jacques

During the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), the Prussian Army sieged Paris. From the safety of his home in Germany, Busch wrote an anti-French picture story, 'Monsieur Jacques à Paris während der Belagerung von 1870' ("'Monsieur Jacques from Paris during the 1870 Siege of Paris"). It portrays a Parisian, stuck in the besieged city, facing starvation. He becomes so desperate that he eats a mouse and chops off his dog's tail to cook it. Finally, he commits suicide through a self-destructive pill that makes him, his dog and two innocent bystanders explode. To modern-day readers, the tale is not only dated, but its francophobian tone, animal cruelty and frivolous depiction of starvation and suicide come across as particular bad taste. Also strange is the fact that Busch ridicules a common Frenchman and doesn't satirize his fellow countrymen besieging Paris.

'Der heilige Antonius von Padua' 1870).

Sint Antonius of Padua

In 1870, Busch published 'Sint Antonius of Padua' ('Saint Antonius of Padua', Moritz Schauburg, 1870), a parody of the lives of Catholic saints. St. Antonius leads a life of debauchery until he becomes a hermit. He devotes his soul to the Virgin Mary and interprets a wild boar as a "sign" of her blessing. The story is filled with blasphemous moments. When Antonius asks a boy who his parents are, he replies: "The bishop Rusticus", before the embarrassed clergyman interrupts him. In another scene considered offensive back in the day, the Devil tries to seduce Antonius by appearing as a ballet dancer. Busch outraged even more religious readers with the final scene, where the Virgin Mary allows Antonius and his pet swine to enter the Heavenly Gates, since "a lot of sheep enter here, so why not a nice pig?" The satirical work coincided with the First Vatican Council, when Pope Pius IX declared papal infallibility a dogma. 'Saint Antonius of Padua' was therefore very popular with non-Catholic readers, but caused controversy among others. On 8 July 1870, the public ministry in Offenburg sued the publisher for indecency and blasphemy , but on 27 March 1871 the judge ruled in Moritz Schauburg's favor. In Austria, Sint Antonius of Padua' remained banned until 1902.

'Die fromme Helene' ("Devout Helen", 1872).

Die fromme Helene

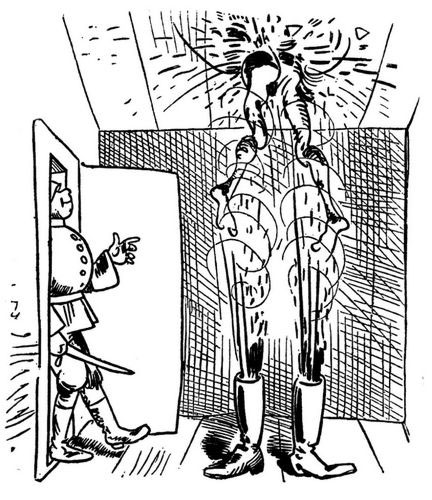

After the controversy over Busch's previous religious satire, 'St. Antonius of Padua', his publisher Moritz Schauburg didn't dare to release another blasphemous book. So Busch went to another publisher, Otto Friedrich Bassermann, to release the picture story 'Die fromme Helene' ("Devout Helen", 1872), arguably his bleakest religious satire. The plot revolves around a Catholic woman who marries an uncultivated businessman, GIC Schmöck (whose name sounds like the Yiddish derogatory term "schmuck"). Since she can't have children, she goes on a pilgrimage, accompanied by her cousin Franz, with whom she was in love since her teenage years but who now decided to become a Catholic priest. Afterwards she gets pregnant and bears a twin, though in Busch's accompanying illustration the boys share a cannier resemblance to cousin Franz than to Schmöck. Soon, Schmöck chokes on his festive meal and dies, while the adulterous Franz is murdered by a jealous servant. Now a widow, Helen devotes her life to her faith, and alcohol. The tale has a cynical conclusion when Helen gets drunk, falls on a burning oil lamp and dies in a fire. Her years of religious devotion turn out to have been a waste of time, since the Devil instantly carries her off to Hell.

'Die fromme Helene' ("Devout Helen", 1872).

'Die fromme Helene' had an autobiographical undertone. Busch based Helene on Johanna Kessler, a rich art patron who once acted as his maecenas. She was married to an older man, with whom she had seven children. Her husband was a rich businessman who didn't care about his wife's interests in painting, sculpture and theatre. Busch was delighted that Kessler believed in his work and gave him public and financial support. At the same time, he was frustrated that a cultivated woman like her was married to such a boorish bureaucrat. The Kesslers presented themselves as rich, devout citizens with a happy family life, while Busch regarded them as hypocritical snobs who left the education of their offspring into the hands of nannies. For him this was a personal matter, since he had been raised by relatives instead of his biological parents. He knew from first-hand experience how it felt to be neglected and alienated. At age 12, when he saw his mother again after several years of being raised by a custodian, she didn't even recognize him at first. Even Mrs. Kessler eventually fell out of his personal favor, since she didn't understand why he wasted his time on drawing picture stories, instead of making more paintings. The pilgrimage subplot in 'Die fromme Helene' was also autobiographical. As a student in Munich, Busch had once visited the Andechs monastery and observed several pilgrims making out in the bushes.

'Die fromme Helene' became an instant bestseller and was translated in many languages. The lines "Ich warne dich als Mensch und Christ: oh hüte dich vor allem Bösen / Es macht Pläsier, wenn man es ist / Es macht Verdruss, wenn mans gewesen" ("I warn you as man and as Christian to watch out for evil / It's fun when you have been there, but a nuisance when you're gone") has become a well-known quote in German literature. In 1965, Axel von Ambesser turned 'Die fromme Helene' into a loose, more family-friendly film adaptation, with cameos from Wilhelm Busch himself (played by Ambesser) and Max und Moritz. The picture received bad reviews and has currently faded into obscurity.

Pater Filucius

Busch's third anticlerical satire, 'Pater Filucius' (Bassermann Verlag, 1872) was the only one commissioned by his publisher, Otto Friedrich Bassermann. The tale centers on a priest, Filucius, who tries to seduce Angelika, Pauline and Petrine, the aunts of the rich man Gottlieb Michael, in order to rob them of their riches. Filucius is aided by the French socialist Jean Lecaq and wants to poison Gottlieb. Their schemes are eventually unraveled and prevented, whereupon Gottlieb can marry his cousin Angelika. The picture story ought to be read as a political-religious allegory. Petrine symbolizes Roman Catholicism and is promiscuous and well-fed. Pauline is a Protestant and is more sober, frugal and thin. Gottlieb represents Germany, while Filucius is a Jesuit. Their religious indoctrination is a threat to the country. Especially when Filucius brings in French socialist ideologies, symbolized by the character Jean Lecaq. When the "villains" are defeated, Germany is "saved" when Gottlieb marries Angelika, who symbolizes the free state Church.

At the time, 'Pater Filucius' was a huge bestseller. Only a year before its release, Germany had unified all of its individual provinces into one nation, with separation of Church and state being included in the constitution. The satire was therefore very recognizable to its readers. Nowadays, this aspect makes it one of Busch's more dated works. Fans also regard it as one of his weakest, since he basically churned it out at his publisher's request, lacking the author's personal stamp. Busch later also dismissed it as something he didn't particularly enjoy working on.

'Schnurrdiburr oder die Bienen' (1869).

Schnurrdiburr, oder die Bienen

In 1872, Busch made a stylistic break with the picture story 'Schnurrdibur, oder die Bienen' ("Schnurrdibur, or the Bees"). In this tale, he refrained from cynical, satirical commentary and made a straightforward funny animal comic, told from the point of view of a group of anthropomorphized bees. Beekeeping had always been one of his interests, since his uncle George Kleine was a beekeeper. 'Schnurrdibur' centers on life in a beehive, where the honey-making insects live like humans. They defend their home against hungry people and animals, who all get their comeuppance. As the tale continues, Busch focuses more on what people do with the hives and honey. Uncharacteristically for him, one mischievous boy actually gets a happy end, disguising himself as a monster to steal a pot of honey from his father's bedroom.

'Bilder zur Jobsiade' (1872).

Bilder zur Jobsiade

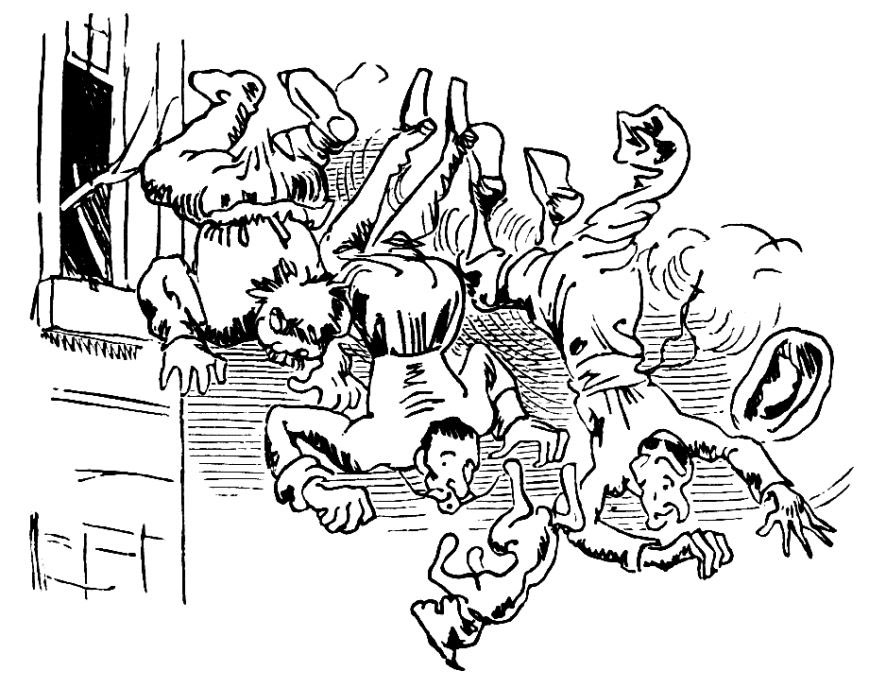

Still in 1872, Busch also released 'Bilder zur Jobsiade' ('Pictures of the Jobsiad'), an adaptation of the 'Jobsiad' (1783-1784), a story written by Carl Arnold Kortum, but bowdlerized and partially rewritten by Busch's publisher Otto Friedrich Bassermann. The story centers on an unlucky man who finds himself in various jobs and situations, without ever finding lasting happiness. Busch was originally commissioned to just illustrate the text, leaving him with little creative possibilities. Only when his publisher rewrote the manuscript in collaboration with Busch, did the work appeal more to him. The 'Jobsiade' is interesting for comic historians, particularly the scene in which the protagonist is questioned by a group of judges. They shake their wig-decorated heads in unison, each time they disagree with our hero's replies. Busch gives the scene a tremendous feel of motion and consecutive sequences. In another image, where somebody blows a horn, Busch places the onomatopoeia "Tu-nuth!" between two straight lines that emerge from the instrument, an early example of sound mimicry within a picture story panel.

'Der Geburtstag, oder die Particularisten' ("The Birthday, or the Particularists", 1873).

Der Geburtstag, oder die Particularisten

'Der Geburtstag, oder die Particularisten' ("The Birthday, or the Particularists", Bassermann, 1873) is a satire by Busch on blind patriotism. The picture story centers on a village in Niedersachsen, where the people want to give their king (the real-life king George V of the German monarchy Hannover) a birthday present. Through a series of mishaps and people's personal egocentric reasons, the project goes nowhere. Only mother Köhm, the innkeeper, is delighted, since all the preparations take place in her bar, where the villagers consume drinks in between.

Napoleon, from 'Dideldum!' (1874). The first image depicts him at Austerlitz, the second at Waterloo.

Dideldum!

In 1874, Wilhelm Busch's publisher released 'Dideldum!' (Bassermann Verlag, 1874), featuring six poems and five picture stories. In 'Trinklied', a man goes to a tavern, gets drunk, but when he can't pay, the inn keeper throws him out, where a policeman jails him for public drunkenness. In 'Der Maulwurf', a gardener tries to capture a mole who is ruining his plants and crops, eventually killing the animal. In 'Romanze', a tailor fancies a corpulent lady, but she dismisses his "crooked needle", whereupon he hangs himself on a coat rack. In 'Die Kirmes', a young girl sneaks out without her parents' knowledge to attend an evening fair. When she returns after dancing all night, she tries to climb back to her room through a wine rack leading to her window, but it breaks and she is kept hanging, until her mother throws the contents of their bedpan on her. Her father, who realizes what is happening, cuts the rack, causing her to plummet down, humiliated. In 'Der Zylinder', a man goes out in his best suit, but when he ogles an attractive woman, his hat is blown off by the wind, crushed under a wheel, while he trips and falls in the mud, a dog steals his hat, forcing him to go back home and dry his clothes.

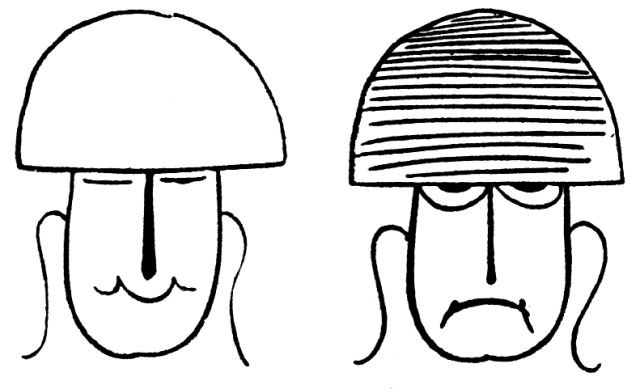

Particularly interesting is 'Anleitung zu historische Porträts' ("Introduction to historical portraits"), in which Busch shows several out-of-context scribbles, allowing the reader to guess who he is portraying. One mushroom-shaped face is revealed to be Napoleon, though with an important distinction. When the figure smiles, he is at Austerlitz, when he looks depressed, he's at Waterloo. The other two scribbles reveal "der alten Fritz" (Frederick the Great) and French ex-emperor Napoleon III. In 1870, Busch had already published a variation of these graphic riddles.

Tobias Knopp - 'Abenteuer eines Junggesellen'.

Tobias Knopp trilogy

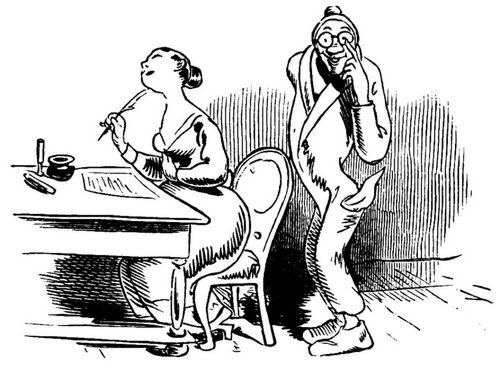

Between 1875 and 1877, Busch published a trilogy, 'Abenteuer eines Junggesellen' (Bassermann Verlag, 1875), 'Herr und Frau Knopp' (1876) and 'Julchen' (1877), about the same central character, Tobias Knopp. Knopp is an overweight bachelor who realizes he might one day die alone, so he desperately wants to find a wife. But in typical Busch fashion, none of the married couples in Knopp's direct environment are truly happy. They either cheat on each other, or are irritated with their obnoxious children. Determined, Knopp still searches for a suitable partner and eventually marries his gullible housekeeper. In the second story, the couple has a daughter, whose own life is the subject of the third tale. One line from this book, "Vader werden ist nicht schwer. Vater sein dagegen sehr" ("Becoming a father isn't hard, becoming a father on the other hand is very hard") has become a famous quote in the German language. The trilogy ends on a bleak note once Knopp's daughter marries, because Knopp now feels his paternal duties have been completed and waits for the Grim Reaper to take him away.

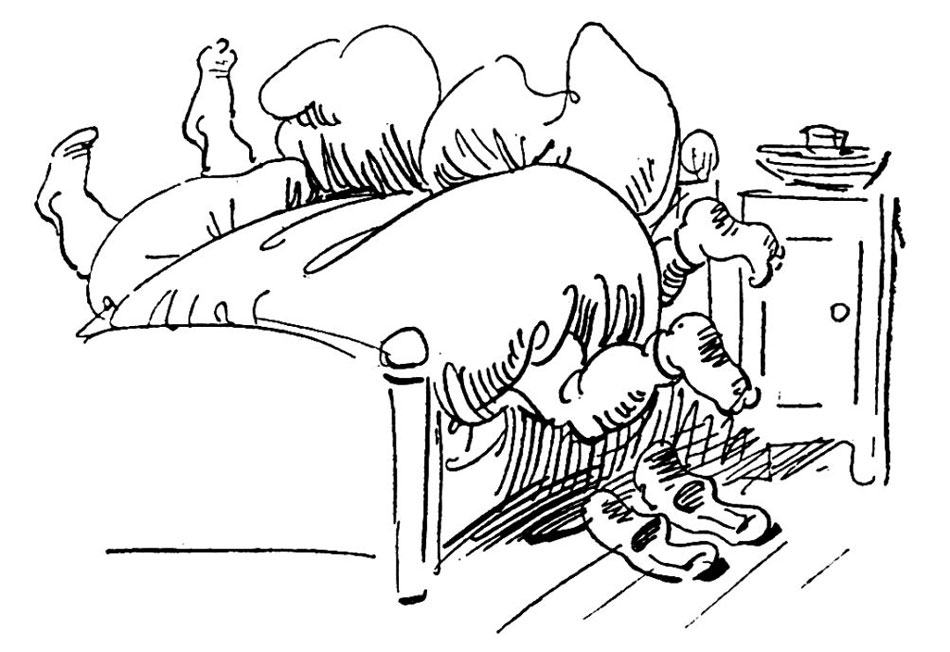

Marital joys in 'Eheliche und Ergötzlichen'.

Biographers regard 'Tobias Knopp' as a reflection on Busch's own bachelor life. He never had stable relationships, and eventually decided to stay single for the rest of his life. 'Tobias Knopp' reflects how having a partner and a family isn't always a bed of roses. Interestingly enough for such a nihilistic reflection on married life, 'Tobias Knopp' is also notable for featuring an implied sex scene. In the chapter 'Eheliche und Ergötzlichen' ("Marital joys"), Tobias and Dorette make out under the sheets. Although no nudity is seen, their pillows and sheets are in motion, with their legs sticking out in silly positions, leaving little to the imagination. The low-brow comedy continues when Busch depicts human faces in the folds of Tobias' behind. These scenes didn't prevent Wolfgang Liebeneiner from adapting 'Tobias Knopp' into a 1950 animated feature, the first of its kind in post-war Germany.

Die Haarbeutel

'Die Haarbeutel ('The Hair Bag', Bassermann, 1877) is a collection of picture stories poking fun at drunk people. Given that Busch was an alcoholic himself, they prove his gift for self-mockery and giving a first-hand visual experience of what liquor does to the brain. In the tale 'Der Undankbare' ("The Ungrateful") for instance, a drunk tries to find his way back home, while the background circles around him. In 'Die ängstliche Nacht' ("The Scary Night"), a man wakes up with a braincrushing hangover, turning his head into a watering can, while a tiny demon plays drums on it.

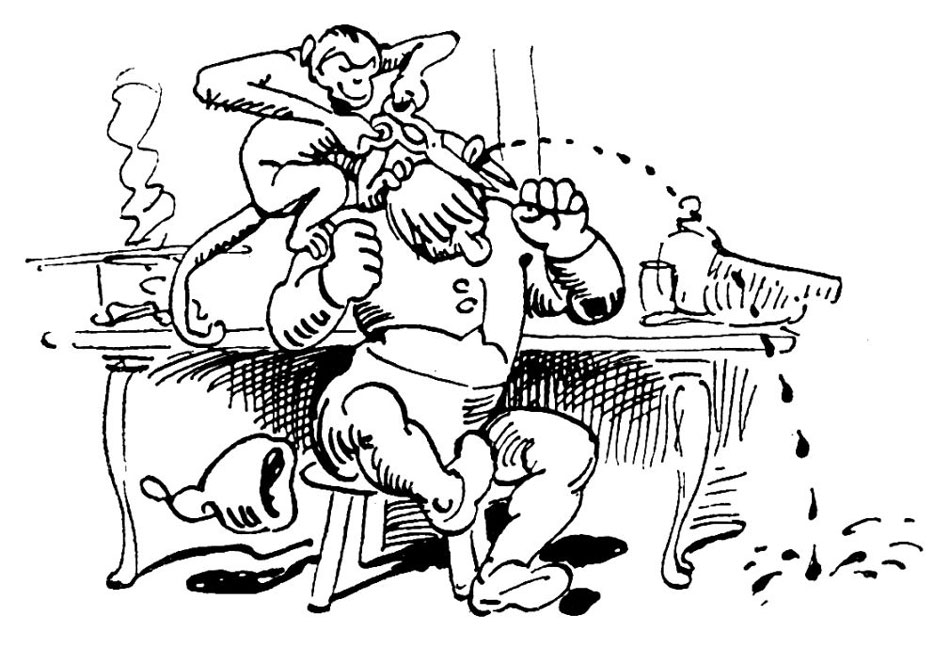

'Fipps, Der Affe' ("Fipps, The Monkey", 1879).

Fipps, Der Affe

In 1879, Busch released 'Fipps, Der Affe' ("Fipps, The Monkey", Bassermann, 1879), a picture story about a mischievous African monkey brought to Bremen by a hunter named Schmitt. He sells the animal to the barber Krüll, but Fipps wounds the ear of one of Krüll's customers, farmer Dümmel. The simian then smashes a hand mirror on Krüll's head and flees the store. Outside, Fipps continues to cause mayhem until he is caught and adopted by a doctor, Mr. Fink, his housekeeper Jette and baby daughter Elise. At first, the family dog Gripps and cat Schnipps distrust the new pet, but eventually grow to like him. Still, after too much monkey business, Fipps is thrown out. He only manages to redeem himself when he saves little Elise from a house fire. Nevertheless, Fipps can't help himself: during one of his strolls, he steals a loaf of bread from a farmer's boy, who happens to be the son of farmer Dümmel, whom he had wounded earlier in the barber shop. Dümmel then shoots Fipps to death. Everybody whom the monkey bothered earlier witnesses his death and Fipps is buried, ending his tale on a sad note.

Strippstörchen für Aeuglein und Oerchen

Busch's 'Strippstörchen für Aeuglein und Oerchen' ("Stork Strips for Eyes and Ears", Bassermann, 1880) features seven illustrated fairy tales, though with grim endings that subvert the fantastical atmosphere. 'Die beiden Schwestern' ("The Two Sisters") for instance, spoofs 'The Frog Prince', with the princess kissing a frog who becomes a prince, only experiencing the opposite effect when she kisses a handsome young man, who transforms into an evil water monster, luring her to the river bottom for the rest of her life.

Der Fuchs, Die Drahen

'Der Fuchs, Die Drahen. Zwei lustige Sachen' ("The Fox, The Dragons. Two Joyful Tales", Bassermann, 1881) are two picture stories by Busch with the handwritten text appearing within the panels. 'Der Fuchs' centers on a fox tormenting a farmer's couple who try to protect their chickens, while 'Die Drahen' stars two young boys who go out to fly a kite, start fighting, but are then whipped by a mean older boy.

Plisch und Plum

With 'Plisch und Plum' (1882), Busch returned to his familiar favorite characters: dogs and little boys. A mean old man, Kaspar Schlich, wants to drown two puppies named Plisch and Plum. The dogs are rescued by two boys, Paul and Peter, but at home, the mutts cause nothing but trouble. A teacher, Mr. Bokelmann, interferes by making both the boys and the dogs nice and obedient by caning them. All ends "well", when Schlich suffers a heart attack, tumbles into a river and miserably drowns. One line from this story, "Aber hier, wie überhaupt, kommt es anders, als man glaubt" ("But here, like in general, things go differently than you'd expect."), has become a well-known phrase in German language.

'Balduin Bählamm, der verhinderte Dichter' (1883).

Balduin Bählamm / Maler Klecksel

Towards the end of his career, Busch became more self-reflective. He wrote and illustrated two picture stories with a semi-autobiographical, even bitter streak. In 'Balduin Bählamm, der verhinderte Dichter' (translated as 'Clement Dove, the Poet Thwarted', 1883) and 'Maler Klecksel' (translated as 'Painter Squirtle', June 1884), Busch respectively satirizes a writer and painter who fancy themselves as geniuses whose works will enlighten mankind, but are in reality pretentious dreamers who hardly get any work done since real-life problems constantly interfere. The writer has to take care of his family and pay his bills. The painter leads a life of debauchery, protected by a rich female patron, yet eventually gives up his artistic aspirations to take over his father's bar. While Busch mocks creative amateurs like himself, he also ridicules art experts who only consider a work "valuable" after seeing how much it is worth.

Final years and death

After achieving his breakthrough with the bestseller 'Max und Moritz' (1865), Wilhelm Busch's writings and drawings became more in demand. In June 1867, he moved to Frankfurt, where his brother Otto worked as a tutor for the banker Kessler. Busch became good friends with Kessler's wife Johanna, who was a well-regarded art and music patron in the city. As his maecenas, she paid for a personal apartment and studio, promoting his paintings to fellow cultural-minded people. Between 1876 and 1880, he was a member of the artists' collective Allotria. But his bohemian lifestyle, combined with tobacco and alcohol addictions, unwillingly drove many people away who could have been beneficial to Busch. As early as 1874, the chain smoker suffered from nicotine poisoning. The same year, his melancholic poetry collection, 'Kritik des Herzens' ("A Heart's Critique", Bassermann, 1874), was a huge flop. In 1881, in a drunken stupor, Busch caused a scene at a social event in Munich. His publisher Otto Bassermann deliberately kept him at home as much as possible, to avoid potential problems with clients. Yet, at the same time, he also sent Busch wine at his request, further worsening the artist's drinking problems. Between 1879 and 1896, Busch lived at his recently widowed sister's place. The eternal bachelor got along fine with her and her children, but didn't allow visitors. Becoming more and more reclusive, Busch's health started to decline. By the 1890s, delirium tremens, caused by decades of heavy drinking, made his hands tremble too much to properly hold a pen.

Busch lived long enough to see a biography published about him, 'Über Wilhelm Busch und seine Bedeitung' (1886) by Eduard Daelen. But the book had a lot of factual errors, causing him to reply with a two-part essay, 'Was mich betrifft' ("About myself"), setting his autobiographical record straight. Between October and December 1886, the text was published in the Frankfurter Zeitung, later followed by another essay, 'Von mir über mich' ("From Me About Me", 1893). Busch's last major story, 'Eduards Traum' ("Edward's Dream", 1891), is a piece of non-illustrated prose, in which the title character observes human society through a series of dreamlike wanderings. More experimental than all his previous publications, it divided readers who either consider it his magnum opus, or less powerful than his illustrated writings. With 'Der Schmetterling' ("The Butterfly", 1895), Busch returned to humor, spoofing the naïvité of German romanticism by giving it a bleak edge. It was his final illustrated narrative.

In 1896, Busch sold his publication rights to publisher Otto Bassermann, moved into a large parsonage in Mechtshausen, and spent his final years organizing his personal archives and writing poetry. In 1908, during a sleepless night, Busch took camphor and morphine and passed away the next morning. He was 75 years old.

Legacy and influence

Wilhem Busch is a major figure in German literature. On 24 June 1930, the Wilhelm Busch-Gesellschaft (Wilhelm Busch Society) was founded, which keeps the memory of his work alive and sponsors the Wilhelm Busch Museum for Caricature and Drawing in Hannover, established in 1937. Apart from Busch's own work, the museum also harbors an impressive collection of caricatures, illustrations and political cartoons by other internationally renowned artists. Busch has a statue in Mechtshausen, where his former house is a museum. The city of Hannover also has a Wilhelm Busch Museum. In Hattorf am Harz, a monument celebrates Busch. In 1958, 1984 and 2007, commemorative stamps and a coin were devoted to Busch and his work. In 2003, the German public television organized the "Unsere Besten" contest, where people could vote for "The Greatest German”. Wilhelm Busch came in at 118th place. Together with Loriot (Victor von Bülow) at number 54, he was the only comic artist in that list. In 2025, Wilhelm Busch was posthumously inducted in the Will Eisner Award Hall of Fame.

His name lives on in the bi-annual Wilhelm Busch Award for satirical and humorous poetry, handed out since 1984.

German stamps devoted to 'Max & Moritz' and Wilhelm Busch.

Long before Wilhelm Busch was born, Germany already had painters and engravers who made sequential illustrations, namely Florian Abel, Hans Burgkmair the Elder, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Jeremias Gath, Hans Holbein the Elder, Bartholomäus Käppeler, Caspar Krebs, Georg Kress, Hans Rogel the Elder, Hans Rogel the Younger, Erhard Schön, Johann Schubert, Hans Schultes the Elder, Lucas Schultes and Elias Wellhöfer. In Austria, Joseph Franz von Göz adapted his play 'Leonardo und Blandine' (1783) in picture story format, while the Swiss David Hess made the illustrated pamphlet 'Hollandia Regenerata' (1796) and his fellow countryman Rodolphe Töpfffer published numerous, widely translated and bootlegged picture stories from the 1820s onwards. German psychologist Heinrich Hoffmann made the picture story 'Der Struwwelpeter' (1845) and his fellow countrymen Carl Reinhardt and Friedrich Lossow respectively the comics 'Meister Lapp und sein Lehrjunge Pips' ("Master Lapp and his Pupil Pips", 1848) and 'Der Vergebliche Rattenjagd' ("The Useless Rat Hunt", 1862).

Busch distinguished himself from most of his predecessors through his virtuoso writing and drawing style. His playful writing style uses alliterative names ('Max und Moritz', 'Hans Huckebein', 'Plisch und Plum') and onomatopoeia. He was swift in anthropomorphizing animals, like Hans Huckebein the raven and Fipps the monkey. Many of his stories feature well-staged slapstick situations that have often been imitated by other humorous artists. Since the Münchener Bilderbogen appeared biweekly and the Fliegende Blätter only had room for one- or two-page picture stories, it forced Busch to keep the gags of his earliest comics short and tight, getting the maximum out of the limited amount of panels he could use. When Busch started making longer stories, they were serialized in chapters. He can be credited as the inventor of the "trickster kid" gag comic. These stories caught on with young readers, proving that children were a major demographic for comics. While this ensured the medium's commercial potential, eventually becoming an industry, it also stigmatized comics as superficial infantile entertainment.

Indeed, as popular as Busch's picture stories were during his lifetime, several adult readers and critics regarded them as straightforward entertainment without much literary or artistic value. Busch didn't think much of his picture stories either. Although he dedicated a lot of time to them, he claimed he merely made them to pay his bills. He always had far higher expectations regarding his "serious" prose stories and paintings. But these were only lukewarmly received by audiences and critics. Busch is a typical example of an artist who underestimated his true talent, in his case making picture stories with humorous rhymes. As a writer, he was an influence on poets like Heinz Erhardt, Erich Kästner, Christian Morgenstern, Joachim Ringelnatz, Eugen Roth and Kurt Tucholsky. As a cartoonist, his influence was even larger. In Germany, he inspired Heinz Schuber, Hermann Schütz and three artists who later moved to the United States: Rudolph Dirks, Gus Dirks and Harold Knerr. The legendary German Disney comics translator Erika Fuchs was another admirer. She used the onomatopoeia "Klickeradoms" in many of her ‘Donald Duck' translations, to the point that younger generations sometimes credited her, rather than Busch, with inventing this particular word.

Busch also influenced the U.S. comic artists F.M. Howarth, Harvey Kurtzman and Gus Mager. He additionally has had followers in Austria (Manfred Deix), Belgium (Eugeen Hermans/Pink, René Follet, Jean-Louis Lejeune), France (Marie Duval, Tomi Ungerer), The Netherlands (Gerrit Rotman, Marten Toonder), Portugal (Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro), Russia (Sergije Mironovic), Spain (José Escobar) and the United Kingdom (Frank Holland).

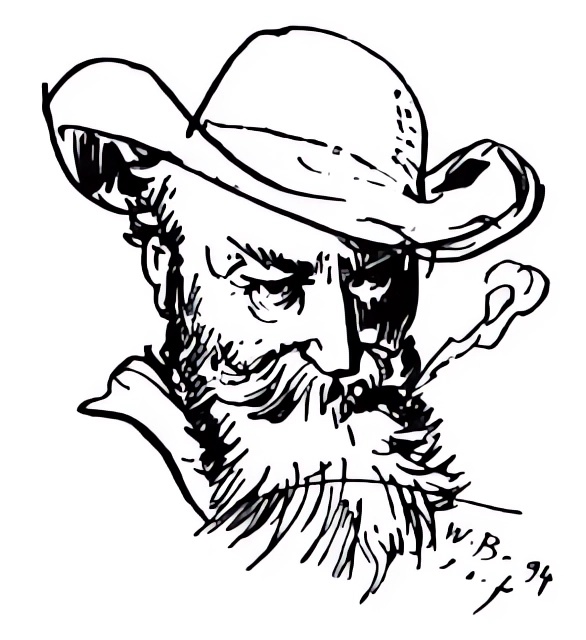

Self-portrait, 1894.