Marcel Ruijters is a Dutch comic creator, best-known for his works based on medieval themes. Starting in the 1980s and 1990s indie comics scene, Ruijters made his mark with his drawings of grotesque creatures, eventually resulting in comic book series like 'Dr.Molotow' (1991-1997) and the 'Troglodytes' (1999-2007). After his underground-flavored beginnings, Ruijters assumed a mock-medieval style for one-shot comic books like 'Sine Qua Non' (2005) and 'All Saints' (2013), as well as his internationally successful graphic novels 'Inferno' (2008) and the Hieronymus Bosch biopic 'Jheronimus' (2016). Since 2017, he has been working on his '1913' (or 'Pola') family saga, a multi-volume graphic novel series set in a steampunk version of 1910s Netherlands. One of the few Dutch graphic novelists with a steady international output, Marcel Ruijters' comics have been published in Danish, Dutch, English, French, German, Hungarian, Polish, Portuguese, Slovene and Spanish.

Early life and influences

Marcel Ruijters was born in 1966 in Tegelen, a town near Venlo in the south-eastern Dutch province of Limburg. Growing up close to the German and Belgian borders, he was exposed to many different cultures, giving him a more cosmopolitan view of the world. His father was art teacher Martin Ruijters, who, at age 75, gained notability as one of the oldest people in the Netherlands to debut as a graphic novelist. Encouraged by his father to make his own creative discoveries, young Marcel filled entire sketchbooks with stories. Among his main graphic influences in the field of comics were Peyo, Benito Jacovitti, Robert Crumb, Charles Burns, Jacques Tardi, The Hernandez Brothers and Paul Bodoni. Ruijters considers the early 'Smurfs' stories by Peyo wonderful fantasy stories with a satirical edge, while Jacovitti's 'Cocco Bill' inspired his tendency to fill up every white space in his panels. He is also influenced by the 19th-century woodcut artist Félix Valloton, an artist he discovered through Tardi, as well as surrealists like Max Ernst and Yves Tanguy. Narratively, he has found inspiration in writers like Edgar Allan Poe, Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Daniël Charms, and post-apocalyptic movies like the 'Mad Max' series.

At age 19, Ruijters began studying painting and printmaking at the Art Academy of Maastricht. As a response to the academy's focus on high-brow museum art, Ruijters began to fill small booklets with his drawings, strips and engravings, which he sold for a couple of guilders to fellow students. After two years, he dropped out because he still felt like an outsider. Although he learned some valuable graphic skills, all he really wanted to do was create comics. Having a strange fascination for monsters, skulls, serial killers and African masks, Ruijters began making paintings and watercolor drawings of grotesque creatures with stretched limbs and wide open mouths and eyes.

Medieval-inspired tarot cards by Marcel Ruijters.

Medieval influences

As his career progressed, Ruijters drew far stronger inspiration from medieval art, a time period he has a strong fascination with. To him, the era is a strange blend between the familiar and the strange. In Europe, many buildings, works of art, fairy tales and legends originate from this era. And still, the majority comes across as otherworldly. Medieval paintings, illustrations and sculptures not only refer to biblical stories, but also to nowadays forgotten Christian legends, myths, martyr stories, superstitions and metaphors. Additionally alienating is that medieval people faced a constant fear that they could die any day. Wars, persecutions, executions, diseases, natural disasters and bad harvests causing famine were common death factors. Peasants tried to survive day by day, and with a reward in Heaven as their only hope, they put much of their faith into the monarchy and Church, to save them from daily horrors. Various medieval artists drew or sculpted visual reminders of mankind's mortality, reminding them to lead a good life, and repent.

Ruijters grew particularly fond of miniature art, the small, hand-drawn pictures that illuminate many medieval manuscripts. While naïve and primitive, Ruijters considers the schematic medieval imagery to be visually strong and highly suggestive. One of his favorite miniaturists is Bartolomeo di Fruosino. In these miniatures, Ruijters observed a connection with modern-day comics. Miniatures use linear art and were all made for reproduction. Biblical stories, chivalry legends, stories of martyrdom, battle chronicles and "danse macabres" all follow central characters, accompanied by text in scrolls or underneath the images. Some miniatures, the so-called "drolleries", are grotesque drawings in the margins of pages. Its style of comedy is typically scatological, with jokes about excrement, flatulence or sex. The "bestiaries" feature drawings of animals, both real and imagined.

In interviews, Ruijters has stated that he learned far more inventive ways to tell stories by studying medieval miniatures than reading work by his contemporaries. One of the things he tries to reduce to a minimum are captions, and instead present narrative transitions in a visual way. Preferring to keep his work expressive, Ruijters also tries to reduce his preliminary sketches, working directly on a clean page. If a wrong line slips into a drawing, he keeps it in. Interviewed by Dirk Rondeltap in Stripschrift #471 (December 2021), he explained: "If you correct it, you may have a more perfect drawing, but not necessarily a more fun one."

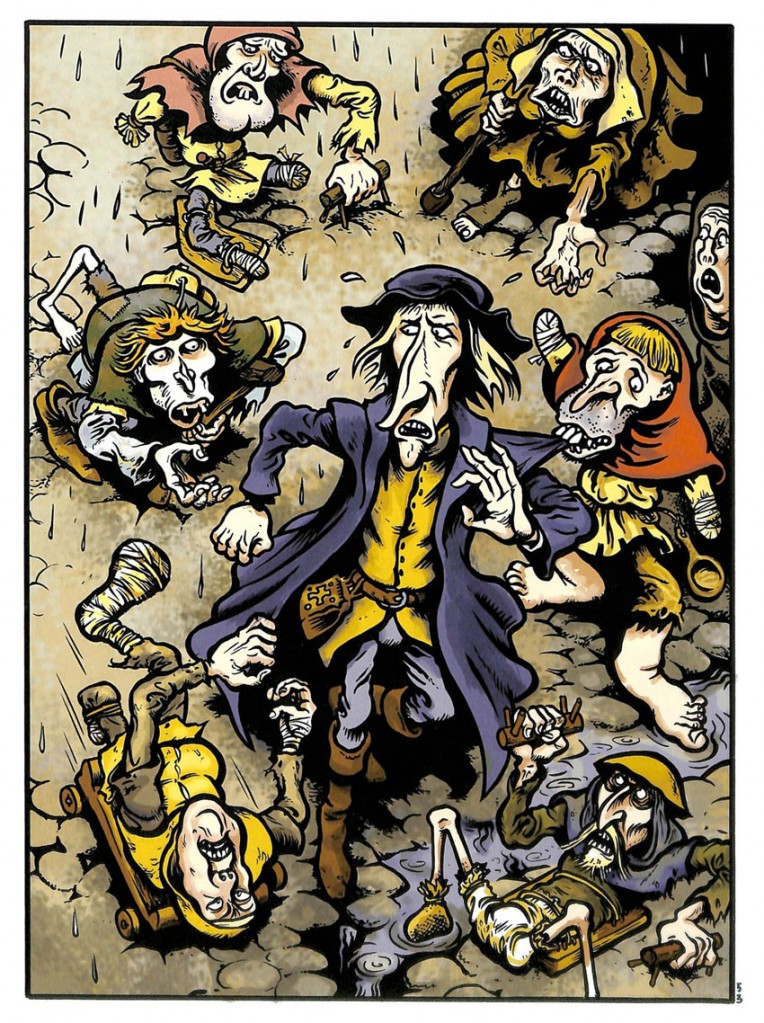

A Day in the Swamp (Coyote #5, March 1984)

Underground comics

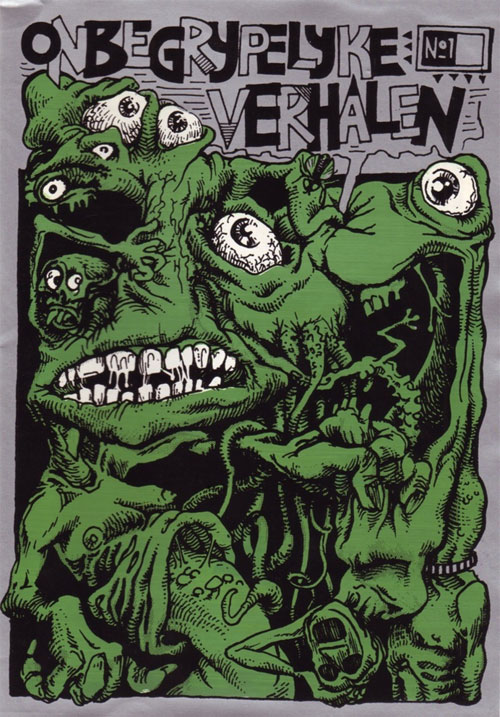

Initially embracing the atmosphere, freedom and relaxed attitude of the underground comics movement, Marcel Ruijters began his career in the Dutch alternative and small press comics scene of the 1980s. In 1984, his first contributions appeared in the indie comic magazine Coyote. When he couldn't find a publisher interested in publishing his offbeat work, he turned to self-publishing. Together with a couple of artist friends, he began the Monguzzi foundation, through which they produced, published and distributed their own Xerox-printed comic books. Between the late 1980s and early 1990s, Ruijters produced dozens of these DIY comic books, aimed at underground audiences both in the Netherlands and abroad. These included thirteen issues of the underground comic magazine Mandragoora (1987-1993), and seven issues of his 'Onbegrijpelijke Verhalen' series ("Incomprehensible stories", 1988-1992), featuring improvised stories with grotesque and surreal creatures.

'Onbegrijpelijke Verhalen'.

Besides solo work by Ruijters, the Monguzzi comics had contributions by others and artwork resulting from so-called "jam sessions" with friends. Among his regular early collaborators were Matthias Giesen and Erik Jongkind, an artist from Amstelveen calling himself Arthur Core. Later issues also had work by Jeroen de Leijer, Chris Crielaard and Berend Vonk. By mail correspondence, Ruijters got in touch with foreign artists, who also submitted work to the Monguzzi publications, such as Jakob Klemencic from Slovenia, Karen Platt from the UK, the American Mike Diana, the Belgian cartoonist Kaprelles, Matthias Lehmann from France, Olle Berg from Sweden and the Italian Gianluca Lerici, better known as "Professor Bad Trip".

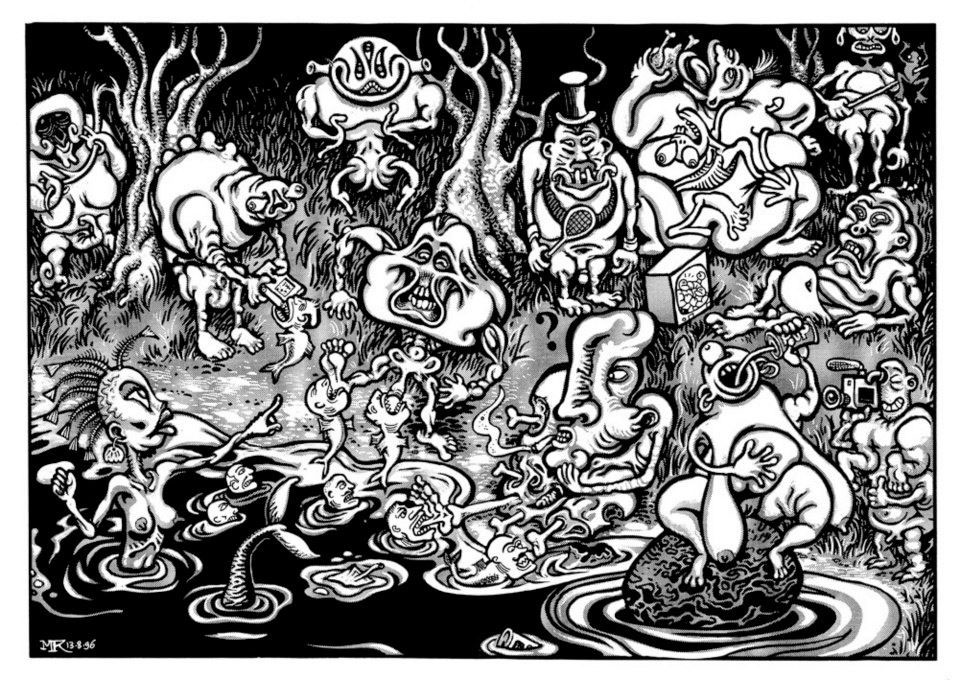

From: 'Thank God It's Ugly' (1996).

Since the possibilities to earn a living from comics in the Netherlands were limited, Ruijters took it upon himself to actively take his work across the borders and present it to an international audience. Besides having his own zines circulating in the international mail-art network, Marcel Ruijters managed to have his drawings and comics printed in underground fanzines like Hello Happy Taxpayers from Bordeaux, France, De Nar from Brussels, Belgium, the Slovenian anthology Stripburger and American titles like Answer Me and Oubliette. In addition, he had his own Mandragoora title distributed in Germany, France, Greece and Belgium. Between 1993 and 2001, Ruijters released seven issues of his English-language anthology series 'Thank God It's Ugly' (1993-2001), featuring artwork by an international selection of comic creators. Also in English were the one-shots 'Schnucki & Ötzi' (1995, a jam with Chris Crielaard) and 'Roadkill' (2010), in which he lampooned his fascination for serial killers.

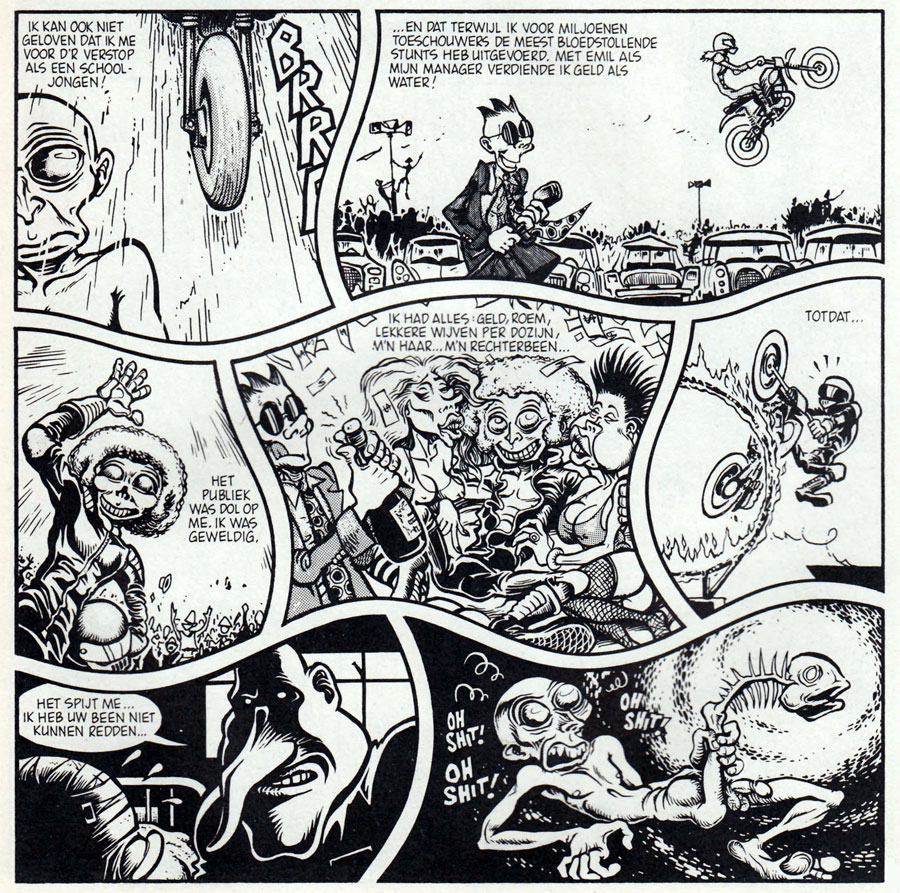

'Dr. Molotow' from Zone 5300 #1 (1994).

Zone 5300: Dr. Molotow

Besides his own self-published comic books, Marcel Ruijters regularly contributed work to regional magazines of the Dutch indie comics scene, including Gag, Bakkes, Posse and Gr'nn. In 1994, he participated in the launch of Zone 5300, a pop-cultural magazine from Rotterdam, initiated by Robert van der Kroft and Tonio van Vugt. Ruijters has remained involved in the magazine as an editor, critic and contributing comic creator, with Zone becoming a regular homebase for several of his recurring comic characters, such as 'Dr. Molotow' and the 'Troglodytes'. His first enduring creation was 'Dr. Molotow', an eccentric brain surgeon in a post-apocalyptic world. After three self-published volumes published through his own Monguzzi imprint - 'De Val van Camp' (1992), 'Het Oog van de Nacht' (1993) and 'Ovidia, Koningin der Kannibalen' (1994) – the Belgian publishing company De Schaar released 'De 7 Clans van Styles Park' (1995) and 'De Vallei der Fluisterende Trilobieten' (1997). Because of the bankruptcy of this publishing house, the sixth volume remained unpublished.

Troglodytes and other bestiaries

Inspired by "Orgone", a concept by the Austrian psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich's of an hypothetical universal life force, Marcel Ruijters created his pantomime comic series 'Troglodytes' (1999-2007), about a cruel and mysterious subhuman species living in murky caves. Three volumes were published by Oog & Blik: 'Troglodytes' (1999), 'Troglodytes 2: Mappa Mundi' (2001) and 'Troglodytes: Vox Insana' (2007). In a way, the Troglodytes marked the transition of Ruijters' underground comix influence into thematics inspired by medieval art, and especially that time period's miniatures. Similar to the miniature subgenre "bestiaries", the 'Troglodytes' stories have no real plot, but center on grotesque animals, demons and other fantasy creatures. Artists who drew such bestiaries depicted various beasts, presented in the style of a travelogue, or what we would nowadays refer to as an animal taxonomy. However, in the Middle Ages, most of the world was still unexplored, leaving people to wonder and fear what might be lurking far outside their own secluded home town or village. Some travelers and explorers described things they had seen, which artists then visualized in drawings. Unavoidably, the travelers remembered things wrong, misinterpreted what they had seen, or simply exaggerated their stories, while the artists further delved into their own fantasies to fill in the blanks. Other artists just plainly made things up, based on what they imagined life in faraway countries or oceans might be like. Typical examples are humans with a head in their body, or one large foot to hop about on. Other creatures were simply believed to exist, because nobody ever proved otherwise, like giants, witches, dragons, unicorns, gnomes, elves, fairies, sprites, trolls, devils, griffins, phoenixes, werewolves, vampires, ghosts, mermaids and gigantic sea serpents.

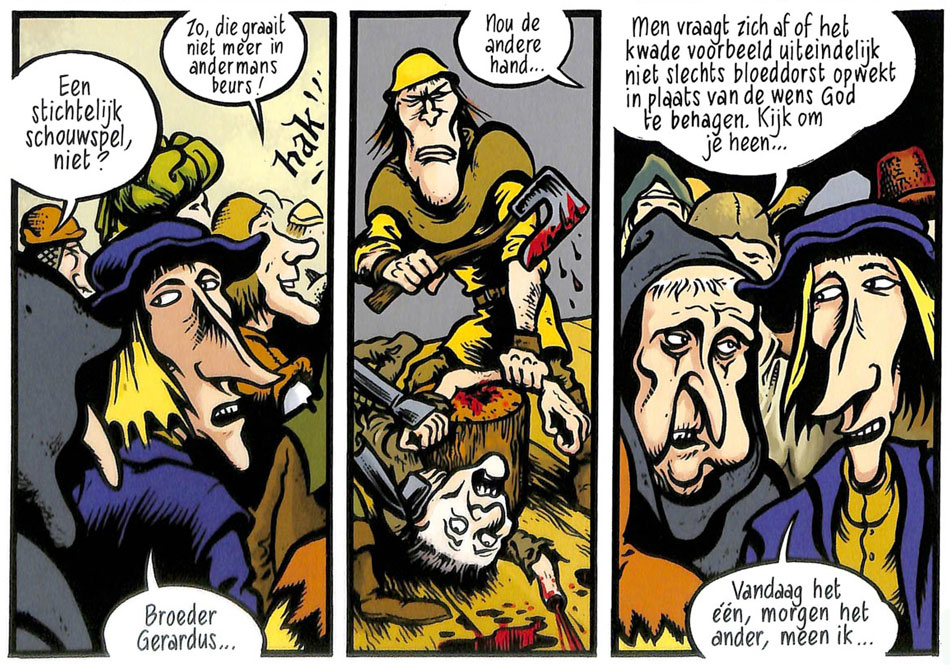

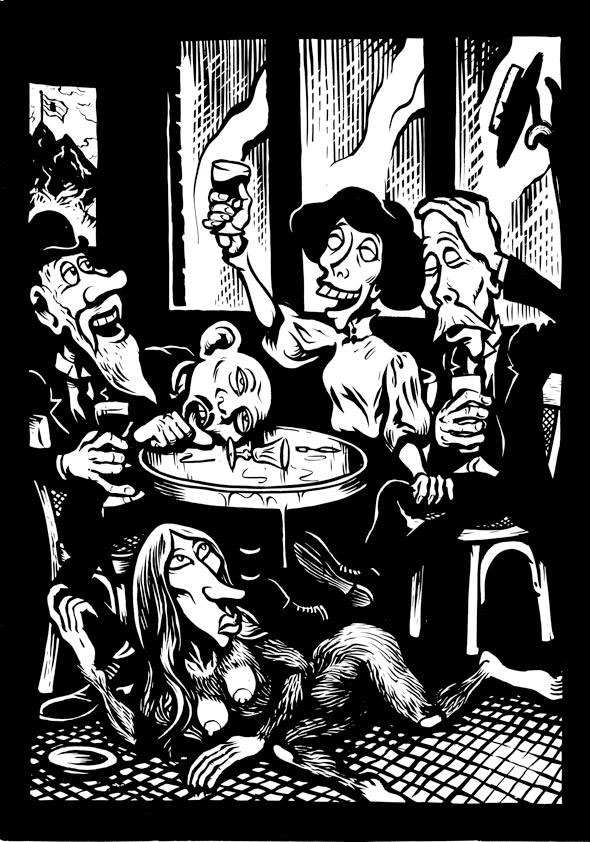

Ruijters liked the naïve but imaginative ways medieval artists envisioned the world around them. His 'Troglodytes' series therefore followed the same path, leaving out all dialogue and context to give the stories the same bewildering, mystic effect. In the same vein, Ruijters made 'Bestiarium' (2004), for which all illustrations were made on scratchboard. The book was released in black-and-white by French publishing company Le Dernier Cri, with a color reprint brought out in 2010. The same company also released a series of tarot cards by Ruijters, titled 'Tarot Corrupt' (2007), and '1348' (Le Dernier Cri, 2010), a book full of medieval cruelty set during the Black Plague. His mini-comic 'A Jest of Nature' (Mille Putois, 1998), was published in Canada. At Le Garage L, he also released a coloring book, 'Colorare Humanum Est' (2011).

Sine Qua Non

Since European culture during the Middle Ages was predominantly Roman Catholic, much of its art cannot be understood without knowledge about its liturgy. While Ruijters' home province of Limburg has a large Catholic community, he himself has been a lifelong atheist, so he has no emotional connection with religious imagery and symbolism. Yet, he does have a fascination with mysticism, since it deals with questions, as opposed to the readymade answers offered by organized religion. His book 'Sine Qua Non' (Oog & Blik, 2005) takes its inspiration from medieval tales of martyrdom, revelation and divine ecstasy, though with a tongue in cheek approach. As main characters, Ruijters chose a group of nuns. In medieval miniatures, many characters look identical, with only their clothing, or the descriptions, as a way to tell them apart, but since nuns all wear the same costume, it's even more difficult. Still, Ruijters knew from Peyo's comic strip 'The Smurfs', coincidentally also set in the Middle Ages, that virtually identical-looking characters could still carry engaging stories. The largely pantomime comic 'Sine Qua Non' was also published in Denmark and France.

With a similar character, Ruijters created the 2012 one-shot 'Totentanz', featuring a medieval nun dancing with Mr. Death. The booklet was initially silkscreened by Les Branquignols, and later reissued as a risography by Ruijters himself. 'Alle Heiligen' (Sherpa, 2013) was Ruijters' first full-color comic book and the first to be translated into Danish (by Forlaens) and Swedish (by C'est Bon Kultur). The work presents fictional depictions of the lives of non-existing Christian saints. A few stories were serialized beforehand in Zuiderlucht, a cultural paper circulating in the city of Maastricht, and in the pop-cultural comics magazine Zone 5300.

Inferno

With his graphic novel 'Inferno' (Oog & Blik, 2008), Ruijters made a loose adaptation of Dante Alighieri's classic 14th-century narrative poem 'The Divine Comedy', a book that also inspired Gary Panter's 'Jimbo's Inferno' comic. In 'The Divine Comedy', Dante imagined himself traveling to Heaven, Purgatory and Hell, where he sees what the afterlife is actually like. He meets several deceased historical, Greco-Roman mythological and biblical characters. Dante had particular fun fantasizing about ironic punishments in Hell and subjecting all his real-life political enemies to eternal torture.

'Inferno'.

To Ruijters, a large part of the poem's appeal were the vivid visual descriptions and its satirical depth. He compared it to a prototypical road movie. Historically, 'The Divine Comedy' was created at the crossroad between the devout Middle Ages and more humanist philosophies of the Renaissance, so the book works both as a Christian allegory and a more secular fantasy. The work was also written when capitalism grew into a dominant economic system. Many European cities flourished as trade centers. This gave Ruijters the idea to present Hell in his 'Inferno' as a corporate business. As he drew his story, the 2008 international stock market crash occurred, causing such an economic crisis that people speculated whether this would be the end of capitalism. The tale would be a symbolic link between the rise and fall of this system.

In religious tradition, Hell is typically a static location where nothing ever changes. Ruijters felt it would be funny to imagine its demons running it like an actual firm. Complete with expected quota to reach and being subject to market changes. Just like 'Sine Qua Non', he made all of his characters female. The book was also released in Hungarian, Portuguese, French and Slovene.

Jheronimus

Ruijters won a lot of acclaim with his first biopic, 'Jheronimus' (Lecturis, 2016), about the medieval Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516). The work was commissioned by the Bosch 500 Foundation and the Mondriaan Art Fund, in light of the 500th anniversary of the artist's death. Bosch, with his vivid and often frightening depictions of Hell, has always been great subject matter for graphic artists. Numerous painters, illustrators and cartoonists had already taken inspiration or paid tribute to his work, but none had ever considered making a biopic. Ruijters soon realized why: very little is known about Bosch's actual life, save for a few town statistics. He discovered that many historians and writers speculated a lot. One of the most recurring claims was that Bosch must have been a drug user for making such surreal paintings. This explanation for Bosch's remarkable imagination overlooked the fact that in the Middle Ages, hallucinogenic experiences were limited to accidental "tripping" through the consumption of poisonous mushrooms or plants. The strange scenes in Bosch's paintings were all metaphors, proverbs and Christian symbolism that his largely analphabetic contemporaries would have understood far better than modern-day audiences.

Ruijters also noticed many writers depicted Bosch as a talent who rose above his contemporaries. This modern-day interpretation of an "artist" doesn't take into consideration that medieval painters were basically draftsmen and that Bosch had an actual studio, working alongside his equally talented siblings. They took commissions, ranging from making religious altar pieces to literally painting somebody's house in a certain color. Bosch's reputation as a "genius ahead of his time" is predominantly posthumous. For his research, Ruijters consulted the city archives of 's-Hertogenbosch, where he inspected Bosch's family register, bills and other legal documents. He noticed that Bosch was very careful with what he spent. Ruijters' bookkeeper once told him that someone's bookkeeping records tell a lot about his personality, so Ruijters portrays Bosch in 'Jheronimus' as a common man trying to keep financially afloat. He is careful and contemplating, a quiet observer of his environment.

Another major challenge considering the real-life Bosch is that the artist spent his entire existence in his birth town. In the Middle Ages, traveling was time-consuming, expensive and often dangerous. Except for traders, pilgrims or occasional royal visits or military expeditions, most people rarely went beyond the close vicinity of their home village or town. Some artists did travel to Rome once in their lifetime, to study the world-renowned local paintings, sculptures and architecture, but, again, there is no direct proof that Bosch ever did so. This left Ruijters with very little basic facts, or geographical variation, to develop a narrative. But the plus side was that he still had a lot of creative freedom. He decided to move the scope of his story. In 'Jheronimus', Ruijters shows how painters in Bosch's lifetime lived and worked. Bosch has to deal with business affairs, unsatisfied customers and deadlines. Ruijters also provides a view of medieval society. Roman-Catholicism is an integral part of life, with many people worrying about their retribution in the afterlife as much as they are concerned with every-day problems. The streets are filthy, while handicapped beggars, fortune tellers and robbers harass the more fortunate people for money. Doctors are indistinguishable from mere quacks. Public executions offer weekly spectacles. Ruijters also referenced historic events, like the Great City Fire of 1463, when Bosch was still a child. Many historians have speculated that the boy must have been a witness of this disaster, making a direct link with the Hellish fires depicted in his paintings.

Working four-and-a-half years on his graphic novel, Ruijters presented his draft to historians. One detail he had to change was the St. Jan Cathedral of 's-Hertogenbosch in the background of various panels, since this particular building hadn't been finished yet during Bosch's lifetime. Some scenes in 'Jheronimus' offer little winks to well-known Bosch paintings. When the artist, for instance, dreams of the Grim Reaper entering his room, Ruijters refers to Bosch's painting 'Death and the Miser'. The lettering of 'Jheronimus' was provided by Frits Jonker. The book was well-received by readers and given national and international media attention. It was translated into Danish (at Forlaget Forlaens), English (Knockabout), German (Avant Verlag), Polish and Spanish.

'Pola' (2019).

The '1913' or 'Pola' series

In 2017, Ruijters broke with style once again by making his first non-medieval-themed graphic novel in years. 'Het 9e Eiland' (2017) is set closer to our times. A European sailor, Scott, is marooned on a tropical island, where he and a local cannibal tribeswoman, Kali, start a lustful relationship and have a baby. As the story progresses, the focus shifts to Scott and his granddaughter, Pola Kazoni, who discover a large Pyramid of Ancient Knowledge, where they meet the Retrosofen, a group of researchers who crave for the past. In the follow-up story, 'Pola' (2019), Pola leaves the island and goes to the "Mainland", where time is frozen in an alternate version of the real-life year 1913. Ruijters did a lot of research about the early 1910s regarding fashions, architecture, politics and technology. Yet, at the same time, he took creative leeway by making it an anachronistic stew of many early and later 20th-century phenomena, complete with more fantastical elements, comparable to a steampunk story. Pola meets a group of avant-garde authors, Klotzbach, Hondsdag and Caroussel, a rich capitalist, Gustav Gustonson, and a communist anarchist, Bodo Hangman. A series of strange events take place, where Heaven has a cat door and the Moon is made out of cheese.

For decades, Ruijters had considered making a graphic novel set in the 1910s, but felt reluctant since French comic author Jacques Tardi had basically made this era his own. Several of Tardi's series are set in the Belle Époque or during the First World War. His signature series, 'Adèle Blanc-Sec', also includes steampunk fantasy plot developments. Eventually, Ruijters overcame his fear of being accused of copying Tardi. After all, his idol's comics are distinctively French, while Ruijters is very Dutch. He could set his story in The Netherlands, or at least based much of its background and culture on his home country. Ruijters' confidence grew to such a degree that 'Het 9e Eiland' and 'Pola' grew into a full-blown family saga, spread over five volumes, all published by Sherpa.

In the third volume, 'Eeuwig 1913' (2020), Pola gets a job as a streetcar driver, while writing a book about her grandparents. The book flops, and she gets fired, but she does find the man of her life, Valdemar. A huge flood gives their life a new goal. They become engineers who try to build efficient dykes to control this aquatic problem. Pola and Waldemar's saga continues in the fourth book, 'De Tweelingparadox' (2021), where society is run by a new party, the A.B.C.P. This regime is a strange mixture between conservative and Communist politics. Pola and Waldemar are confronted with a group of mummies in the Museum of Natural History, who turn out to be living fossils of extraterrestrial origin. Politician Bodo Hangman sees the opportunity to make a secret deal with the aliens. Meanwhile, Pola discovers a portal to a parallel universe, bringing a twin version of herself into her world. In 2024, the fifth volume, 'Observator' (2024), was released, followed in 2025 by 'Alles Hangt Samen'.

'Pola'.

Other projects and collaborations

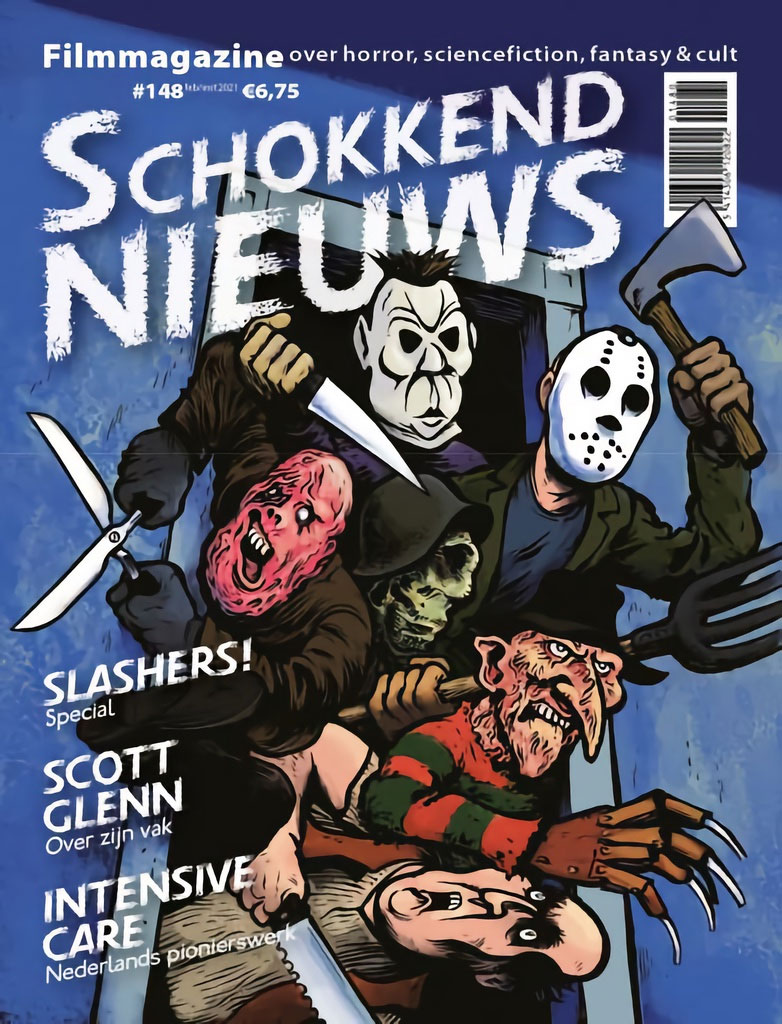

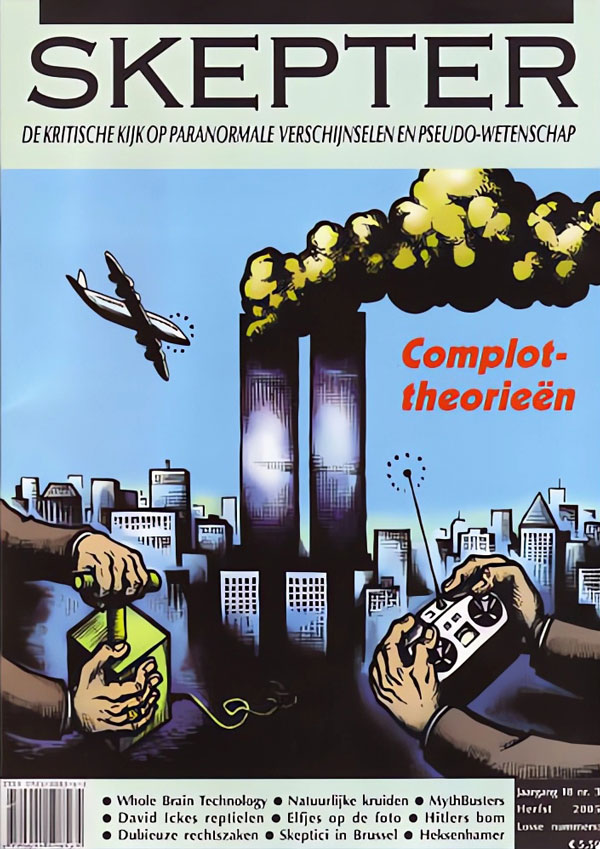

A prominent figure in the Dutch indie comics scene, initially working from Sittard and since 2002 from Rotterdam, Marcel Ruijters has also worked on commercial assignments. Among his more mainstream clients have been the popular science magazine Skepter, the children's monthly Sesamstraat Maandblad, the youth magazine Webber, the horror movie magazine Schokkend Nieuws, the jigsaw puzzle and games company Jumbo and the ICT-innovation organization Kennisnet. For the opinion magazine De Humanist, he has created political drawings. Together with Maaike Hartjes, Mark Hendriks, Albo Helm, Jean-Marc van Tol and Nardja Kerkmeer, he was co-founder of Nukomix (2000), a collective and platform aimed at the promotion of different and more innovative forms of comics in the Netherlands. Between 2015 and 2018, Marcel Ruijters had a partnership with Gwen Stok, with whom he made a series of large ink drawings under the "Juhla" banner. Ruijters was also a regular artist in the Dutch-German underground comics magazine Kutlul (2016-2023). For the regional newspaper Dagblad De Limburger, Ruijters has been writing comics criticism.

Cover drawings for the magazines Schokkend Nieuws and Skepter.

Graphic contributions

Ruijters was one of several artists to make a statement against war in the compilation album 'Signed by War HC' by the Anti War Action Foundation (1994). In 2002, Ruijters, Mike Diana, Jakob Klemencic and Chris Crielaard held the group exhibition 'The Lost Comics Tribe' in the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht. In issue #424 of Zone 5300 (2004), he drew a short biopic about Prescott Bush, father of U.S. President George Bush Sr. and grandfather of George Bush Jr. This particular comic was also translated into English and included in the Fantagraphics compilation comic book, 'The Bush Junta' (2004). Ruijters also contributed to 'Honey Talks: Comics Inspired by Painted Beehive Panels' (Forum Ljubljana/Stripburger, 2006), Menno Kooistra's Dutch horror anthology comic book 'Bloeddorst' (2007) and 'Film Fanfare. De Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse Film Verbeeld in 51 Strips' (De Bezige Bij, Oog & Blik, 2012).

In 2014, Ruijters was one of several artists to contribute to 'Bedankt, Joost!' (SBN, 2004), a homage to comics journalist Joost Pollmann, brother of Peter Pontiac. In 2016, Ruijters drew a comic for Stijn Schenk's 'Mensen – Grafische Verhalen over Openheid en Verbinding' (2016), a booklet collecting graphic stories about different kinds of mental illness and their acceptance in our society. He also contributed to Schenk's 'Verhalen van Vrouwen' (2019), featuring true stories of women who have been victims of abuse, suppression or social exclusion. Ruijters additionally lent his talent to the second volume of the anthology series 'Op Missie' (Strip2000, 2016), in which comic artists visualize true-life stories by war veterans.

Ruijters has also designed cover art for underground musical acts, like Mandragoora, Hystereo, Midnight Rider ('Against Our Will', 1992), Wasteland ('Vacuum', 1992), Undeclinable Ambuscade ('African Song', 1996) and Army of God ('Salvation', 2022). With Chris Crielaard, he designed the cover for the compilation album 'Yodeling Sucks' (1995).

Recognition

During the 1992 comic festival of Haarlem, Marcel Ruijters was awarded the NZH Prize for "most promising talent", which included prize money of 1,000 guilders (approximately 455 euros). In May 2008, 'Inferno' won the VPRO Award for "Best Dutch Graphic Novel" During an art exposition held in Gallery Lambiek in April-June 2008, all 119 original pages from the graphic novel were on display. During the Stripdagen comic festival, held in Gorinchem on 7-8 March 2015, Ruijters was awarded the Stripschap Prize for his entire body of work.

Marcel Ruijters signing at the opening of his 'Inferno' exposition at Gallery Lambiek (25 April 2008). He signed in our store again on 7 June 2024.