Corentin - 'Le Poignard Magique'. Dutch-language version.

Paul Cuvelier was one of the classic artists of post-war Franco-Belgian comics. Together with Hergé, Jacques Laudy and Edgar P. Jacobs, he was among the original creators for Tintin magazine, working for the magazine from the start in 1946 until the early 1970s. He is best-known for his historical adventure series about the 18th-century orphan boy Corentin Feldoë (1946-1973), but has also drawn the medieval series 'Flamme d'Argent' (1960-1963), the adventures of the Native American 'Wapi' (1962-1966), the investigations of the charming 'Line' (1962-1972) and the groundbreaking erotic graphic novel 'Epoxy' (1968). Cuvelier's comics output was characterized by long intervals, as the artist always drifted between his fine arts ambitions and the more financially rewarding comic industry. The connecting thread between his activities in these two art forms was his strong fascination for the aesthetics of human anatomy.

Early years

Paul François Marie-Ghislain Cuvelier was born in 1923 in Lens, a town near Mons, in the Walloon province of Hainaut. He was the third of seven children of country doctor Charles Cuvelier (1887-1968) and Louise Labrique (1896-1998), an amateur artist. Already as a child, Paul showed an almost immediate talent for drawing and was gifted with the powers of observation. He regularly headed out to make drawings and paintings of the outdoors. For his two younger brothers, he was also an avid storyteller, who decorated his tales with drawings and self-fabricated marionettes. Cuvelier's main sources of inspiration were adventure novels like Robert Louis Stevenson's 'Treasure Island', Daniel Defoe's 'Robinson Crusoe' and Paul Féval's 'Corentin Quimper', as well as the 19th-century etchings of Gustave Doré and religious illustrations. As a child, comics were not among his prominent interests, although he enjoyed reading the adventures of Hergé's 'Tintin' in Le Petit Vingtième, a magazine that also published one of his childhood drawings when he was seven years old. Because of this artistic background, it is difficult to pinpoint direct influences on Cuvelier's later comics work. The artist has later named Alex Raymond, E.P. Jacobs and Hergé as sources of inspiration. Later in life, he also expressed his admiration for André Franquin, Jean Giraud, Jean-Claude Mézières, Jacques Martin and Fred.

In 1941, the eighteen-year-old Cuvelier ended his studies of Latin and Greek at the university of Enghien, and became an apprentice in the atelier of painter Louis G. Cambier. He later enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Mons, but he eventually dropped out. According to legend, this was because his tutor, painter Louis Buisseret, informed him that he couldn't teach the talented young man anything new.

'Tom Colby'.

Early comics

By 1943, Cuvelier developed a new story to tell his younger brothers starring a character called Corentin Feldoë, a name inspired by his favorite novel heroes Corentin Quimper and Robinson Crusoë. The artist quickly felt a connection with his creation, and he captured his exotic adventures in a series of eight watercolor paintings. In 1945, Cuvelier decided to give the comics medium a chance and, through a friend of his father, he was introduced to Hergé. The creator of 'Tintin' was impressed by the young man's work, especially his 'Corentin' watercolors. To get him started, Hergé provided Cuvelier with a script, which he wrote in collaboration with his co-worker Edgar Pierre Jacobs under the joint pen name "Olav". This resulted in Paul Cuvelier's first comic, the western 'Tom Colby : Le Canyon Mystérieux'. The artist signed the strip with "Sigto", his first name written in Greek. In 1947, the story finally saw publication in a book by Éditions du Berger, but by then the artist was already working on his next project.

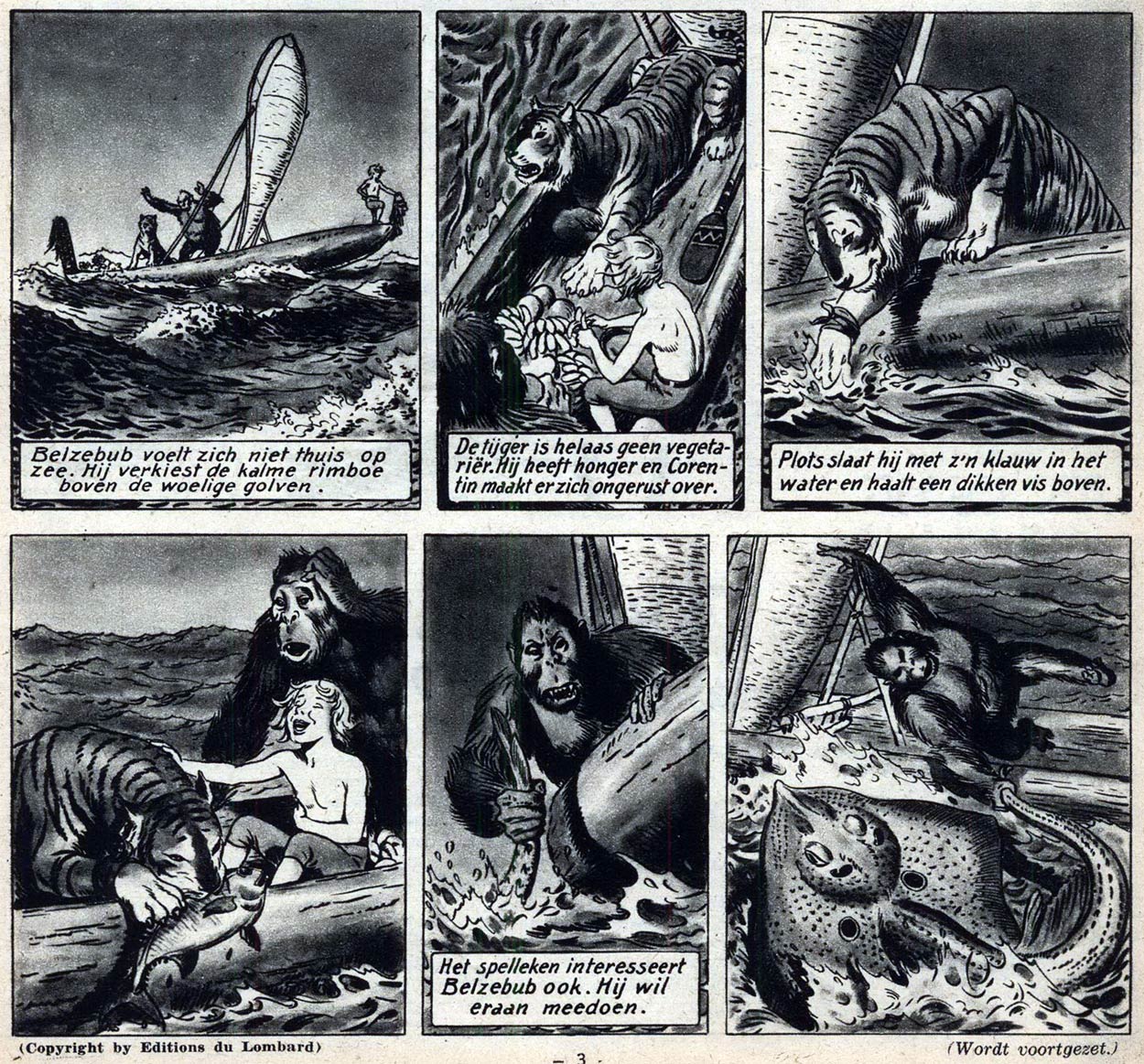

'L'Extraordinaire Odyssée de Corentin Feldoé' (Dutch-language version from Kuifje #3, 1947).

Corentin

On 26 September 1946, the first issue of the magazine Le Journal de Tintin appeared, a cooperation between Hergé and publisher Raymond Leblanc. In this first issue, Cuvelier's comic serial 'L'Extraordinaire Odyssée de Corentin Feldoé' (1946-1947) took off, printed in black-and-white with effects in washed ink. The main hero is a young orphan boy from 18th-century Brittany (Bretagne), who flees from his abusive and alcoholic uncle. He heads out for great adventures as a stowaway, and ends up in India after the ship was wrecked after a pirate attack. During his adventures, Corentin finds two unlikely sidekicks in the gorilla Belzébuth and the tiger Moloch. He also befriends an Indian boy called Kim, who accompanies him on all his further adventures. Other recurring allies are Princess Sa-Skya and her father, the Sultan of Minpore.

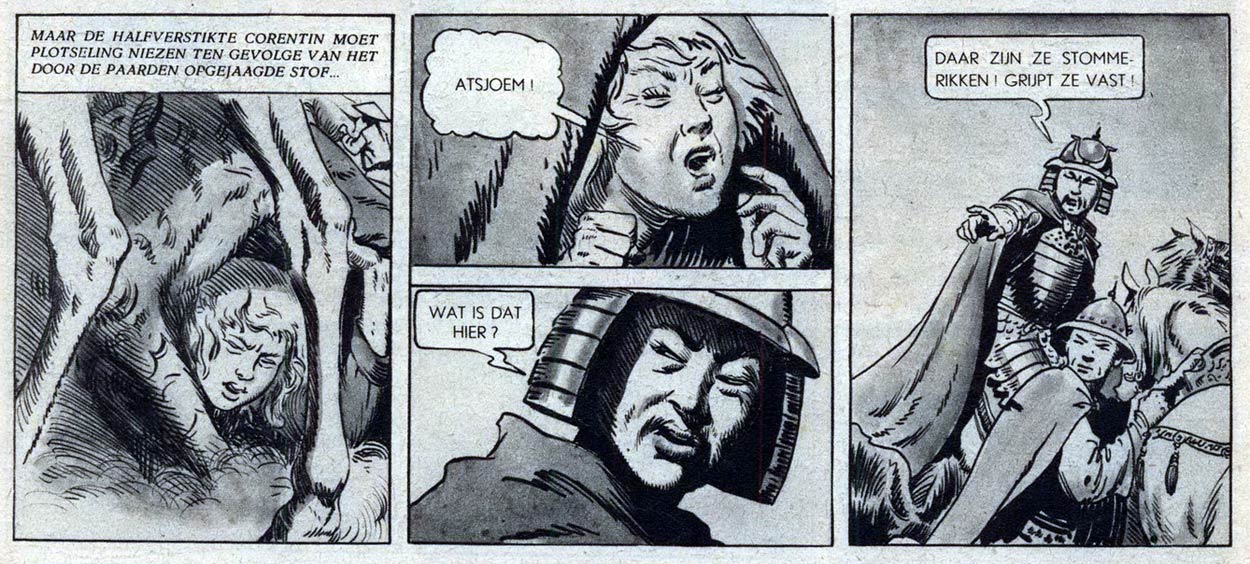

'Les Nouvelles Aventures de Corentin' (Dutch-language version from Kuifje #22, 1948).

Since Cuvelier's artistic interests didn't have their roots in comics, he had difficulties with crafting his story. Tintin's editor-in-chief Jacques van Melkebeke helped him out with the plot of the first story, and then wrote the second adventure, 'Les Nouvelles Aventures de Corentin Feldoë' (1947-1948), which took off immediately after the first one ended. This new story brought Cuvelier's heroes to China. Still, the early 'Corentin' narratives tend to lack a solid plot. They generally aim for dramatic effects, with Corentin and Kim falling from one adventure into the other. The chain of accidental events is filled with several kidnappings, malicious villains and other dangers. Later stories have more eye for a plot, but the overall theme depends on Cuvelier's personal mood and the contributions of the scriptwriter on duty.

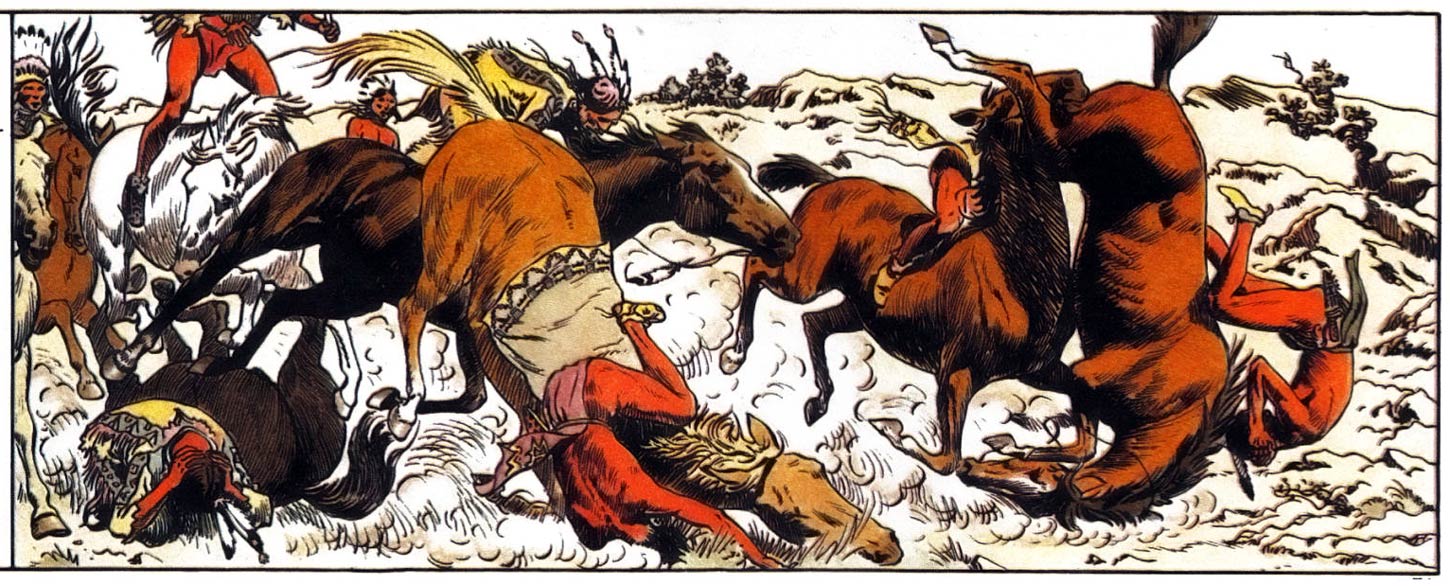

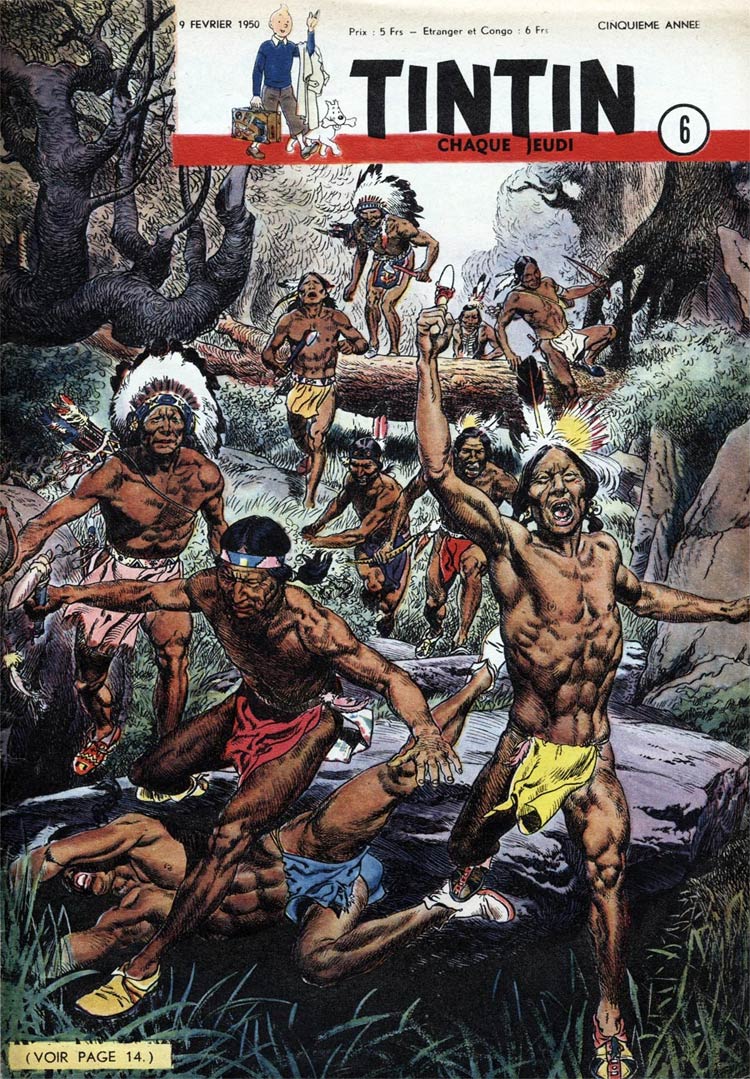

'Corentin Chez les Peaux–Rouges'.

For the third story, 'Corentin Chez les Peaux-Rouges' ("Corentin Among the Redskins", 1949-1950), Cuvelier received help from the script of Albert Weinberg. An oddball in the collection, the story doesn't star the original Corentin, but his grandson. Corentin III and his mother are roaming the US prairies in search of Corentin's stepfather, an American army colonel called William. The story also stands out for its positive portrayal of Native Americans. Unlike most pop culture outings of the time, the "Indians" are not presented as enemies, but as Corentin's allies. When the story concluded, Cuvelier took his first of many long breaks from the comic industry.

'Corentin et le Prince des Sables'.

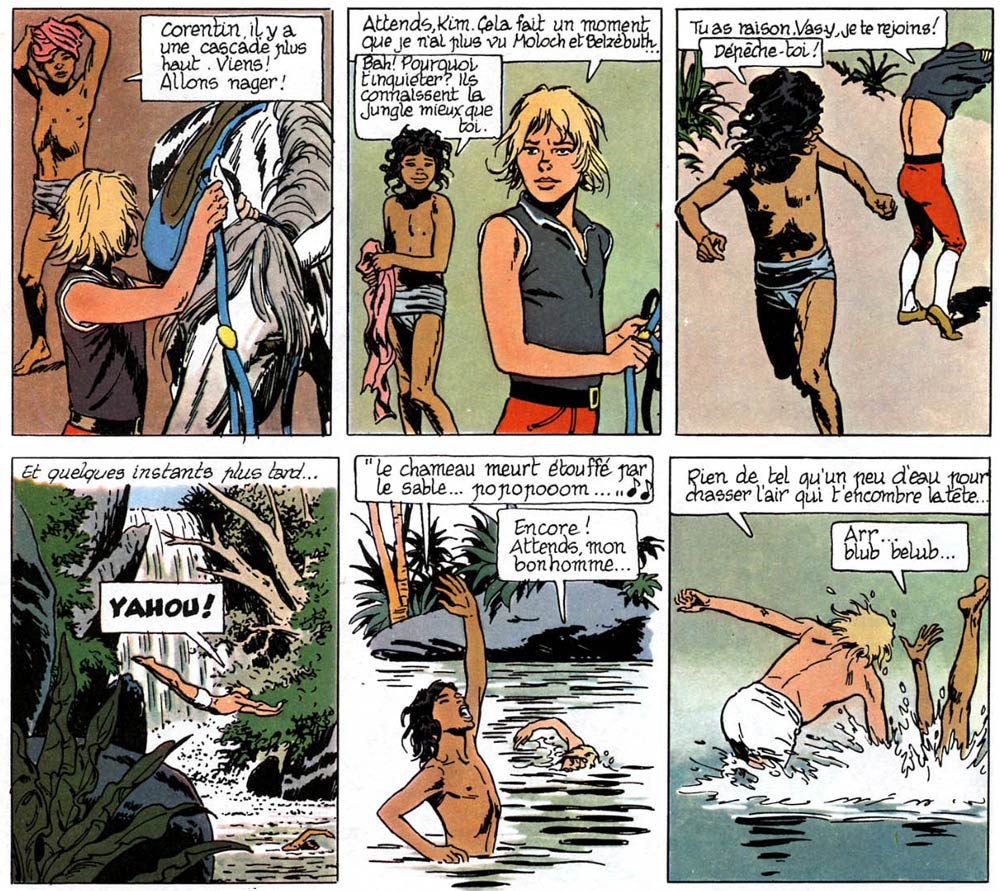

Readers had to wait until 1958 before the next 'Corentin' story appeared in Tintin's pages. 'Le Poignard Magique' ("The Magic Dagger", 1958-1960) stars the original Corentin Feldoë again. After their previous adventures in China, Corentin and his friend Kim have returned to India, where they are reunited with Belzébuth the gorilla, Moloch the tiger and princess Sa-Skya. The latter's father, now the Rajah of Sonpie, sends Corentin on a quest to reclaim a magical dagger. The initial plot and script were written by Gine Victor, an acquaintance of Cuvelier from the artistic circles of Mons. However, she had no experience with comics, and the collaboration ended as the artist was dissatisfied with the story's progression. This time Michel Greg stepped in to help out the struggling artist.

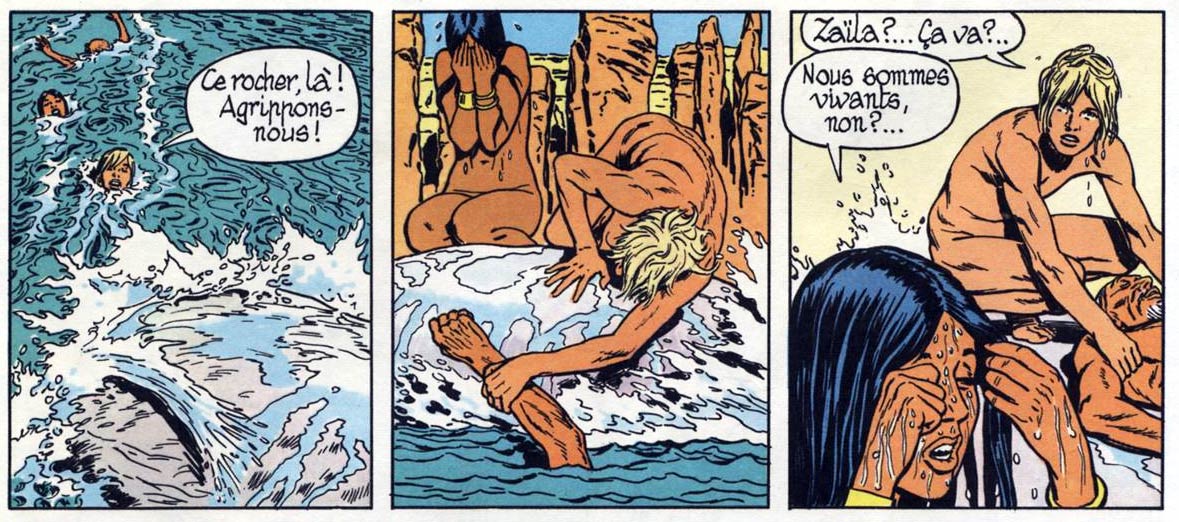

After yet another long interlude, Corentin returned in 'Le Signe du Cobra' ("The Sign of the Cobra", "1967), this time scripted by Jacques Acar. Jean Van Hamme provided the scripts for the last two completed stories, 'Corentin et le Prince des Sables' ("Corentin and the Prince of Sands", 1968-1969) and 'Le Royaume des Eaux Noires' ("The Black Water Kingdom", 1973). The Van Hamme stories are mostly situated in Arabia, where the beautiful Zaïla is introduced as a new love interest for Corentin. By then, the character has aged considerably since his first appearance. In the final story, Corentin and Zaïla end up in the realm of a half human/half extraterrestrial creature. These science fiction elements were a far step from the magical and poetic atmosphere Cuvelier desired, and in the end didn't satisfy him.

Corentin - 'Le Royaume des Eaux Noires'.

Later Corentin revivals

Even though its quality and consistency have been variable, 'Corentin' is still considered one of the most important works in Franco-Belgian comic history. Since 1950, publisher Le Lombard has released Corentin's adventures in book format. The collection was relaunched in 1992 with new colorizations by Marc-Renier and Marie-Noëlle Bastin. In 2010, the publisher collected the entire series in two large volumes. The character was even revived in 2016 with the album 'Les Trois Perles de Sa-Skya', drawn by Jacques Martin's former co-worker Christophe Simon, The plot of this new story was a reworking of a novel Jean Van Hamme had written with a character from one of Tintin's 1970s pocket publications. At the time, Cuvelier had refused any participation with the work, since he felt Van Hamme took too much liberty with Corentin's character traits. Parts of the plot also created continuity errors with regard to the 1949 one-time Far West episode starring the protagonist's offspring.

TV and novel adaptations

Years after their creator's death, the adventures of 'Corentin' were adapted into an animated TV series, 'Les Voyages de Corentin' (1993-1998). Twenty-six episodes were produced by Lombard's animation department Belvision in cooperation with Média-Film and Saban International. Animation veteran Picha was involved with the project, while Jean van Hamme was screenwriter. In 1995, writer Jean Cheville and illustrator Nadine Forster adapted four episodes of the TV show into a series of illustrated books for publisher Lombard.

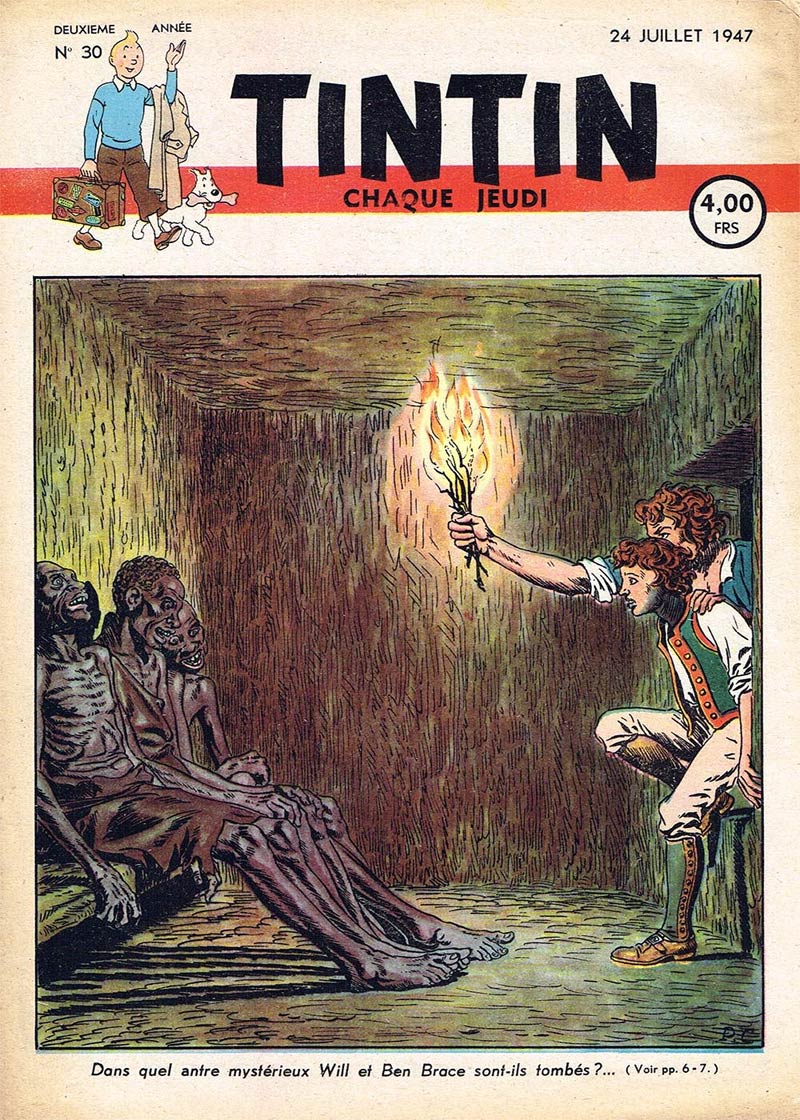

Cover illustrations for Tintin issue #30 (24 July 1947) and #6 (9 February 1950).

Other work for Tintin

During the early years of Tintin magazine, Cuvelier was a productive artist. Besides creating his comic series, he livened up the magazine with many beautiful cover illustrations, often with his signature hero Corentin. He was the illustrator for a 1947 serialization of the naval story 'À La Mer' by Captain Thomas Mayne Reid (1818-1883), which ran as an illustrated text in the magazine. In the following years, Cuvelier visualized several other written stories in Tintin, and additionally created various imaginative advertising comics promoting the chocolate brand Côte d'Or, such as 'La Légende du Bon Chocolat Côte d'Or' (1947) and the more contemporary comic strip serial 'La Prodigieuse Invention du Professeur Hyx' (1948-1949).

'De Wonderbare Uitvinding van Professor Hyx'. Dutch-language version of 'La Prodigieuse Invention du Professeur Hyx', 1948-1949, made to promote the chocolate brand Côte d'Or.

In 1951, during his first excursion into fine arts, Cuvelier established his own atelier in Mons, where he focused on painting and sculpting. One of his early assignments was designing a tapestry for the UN headquarters in New York. During this period, he was still present in Tintin magazine with his illustrations for the western text story 'Texas Slim' (1952) by Marcel Artigues, although for a couple of episodes, he was replaced by René Follet. In the following year, Cuvelier illustrated the text serial 'Bento Cheval Sauvage' (1953) by Holesch Dita. He also illustrated two short historical comic stories; the first from a script by Gine Victor ('En Ce Temps–Là', 1953); the second from his own plot ('Si l'Iliade m'Etait Conté', 1956).

'Flamme d'Argent' #2 - 'Le Croise sans Nom'.

Flamme d'Argent

In the 1960s, Cuvelier was again a prominent staple in Tintin magazine, although at first he felt reluctant to resume 'Corentin'. Instead, he tried his hand on several new comic series. The first of these was 'Flamme d'Argent' (1960-1963), another historical series based on the childhood stories he used to tell his brothers. Scriptwriter Michel Greg turned the concept into a full-fledged comic script. Set in the Middle Ages, Ardan des Sables returns from the crusades disguised as a minstrel. Under his secret identity "Flamme d'Argent" ("Silver Flame"), he, like Robin Hood, stands up for the poor and the needy. In the first self-titled story (1960), Ardan helps the young Edric - who is accompanied by the lumberjack's son Fennec - reclaim the land of his father from a false feudal lord. In the second adventure, 'Le Croisé sans Nom' ("The Nameless Crusader", 1962), he accompanies the boys in search of Edric's father, a crusader in Antioch. In the final episode, 'Le Bouclier de Lumière' ("The Shield of Light", 1963), Cuvelier's hero takes over a royal assignment to transport a treasure to Pedro I of Aragon. With that treasure, a mercenary army must be established to drive the Moors out of Europe. When at one point Cuvelier turned ill, the artist couple Fred and Liliane Funcken filled in for a couple of episodes. While the series had dynamic and imaginative artwork, Cuvelier grew tired of it, and 'Flamme d'Argent' was discontinued after only three stories.

Wapi

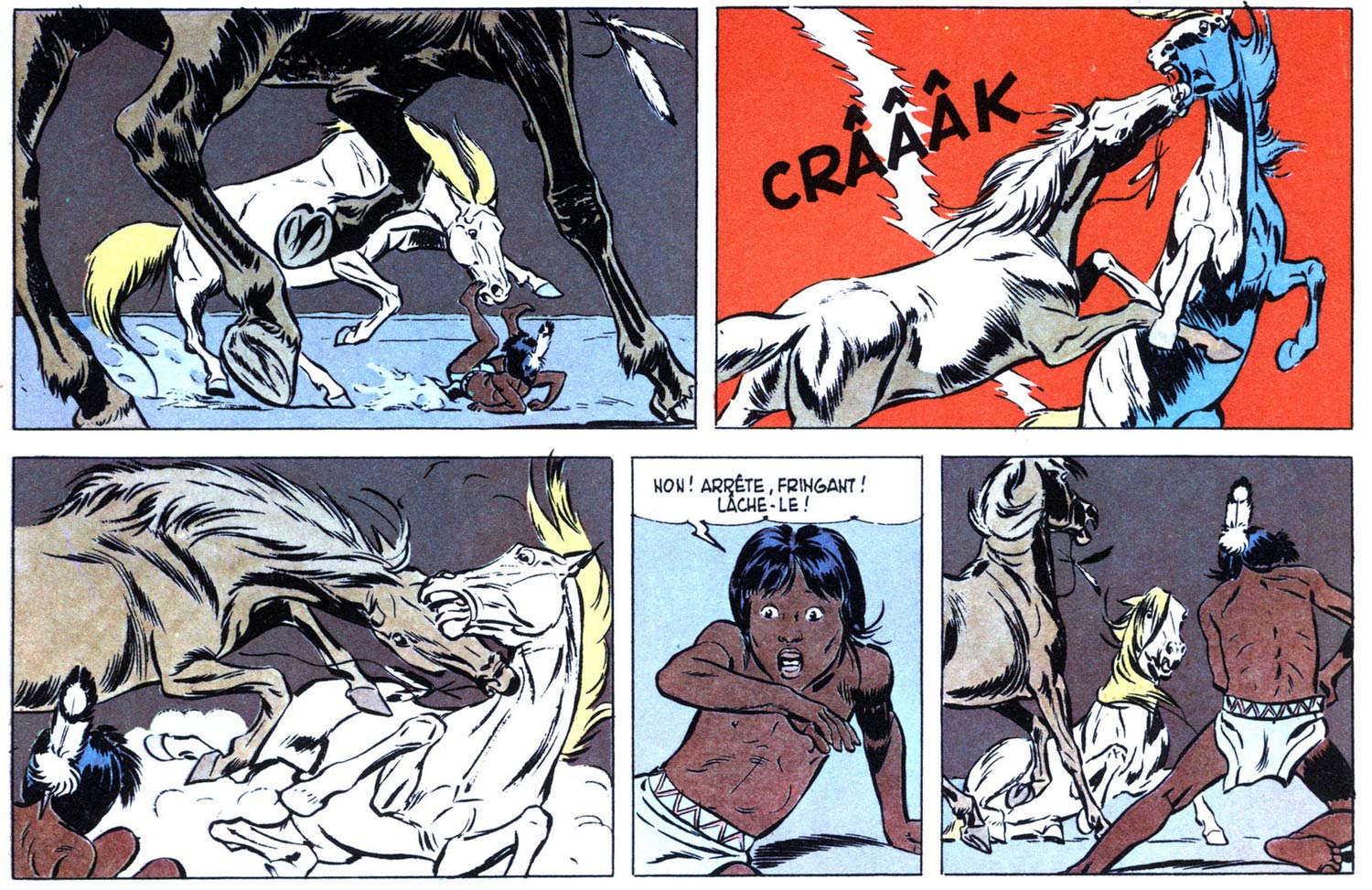

After 'Flamme d'Argent', Cuvelier turned to the Far West and ancient Native American legends for 'Wapi et le Triangle d'Or' ("Wapi and the Golden Triangle", 1962), a one-shot story scripted by Cuvelier's friend and colorist Benoit Boëlens (who worked under the pen name Benoi). In 1966, 'Wapi' appeared one more time in a short story written by Jacques Acar.

Les Aventures de Line - 'Le Secret du Boucanier' (1964).

Line

In 1962, Cuvelier was also present in Tintin's sister magazine Line, which aimed at a feminine readership. With Greg as scriptwriter, he took over the title comic until the magazine's cancellation in 1963. The character Line was created in 1956 by writer Nicolas Goujon and illustrator Françoise Bertier. In the years that followed, several authors made their own interpretations of the feature; first Charles Nugue and André Gaudelette, then the cartoonist Rol. Between 1963 and 1965, Cuvelier and Greg continued Line's dynamic detective stories in Tintin. A final story, starring a more mature Line, appearing in 1971-1972. One of the artists who assisted Paul Cuvelier on 'Line' was Mittéï.

Line - 'La Caravane de la Colère' (1971).

Art style

Unlike most of the other authors of Tintin magazine, Cuvelier wasn't forced to work in Hergé's "Clear Line" art style. Instead, his early black-and-white stories showed a closer resemblance to 19th-century etchings, although they lost most of this effect after being colorized for the subsequent book publications. From 1951 on, 'Corentin' was published directly in color, and the artist applied a more refined drawing style with less use of shading. Contrary to his friend and colleague Jacques Martin - the creator of Tntin's other historical epic, 'Alix' - Cuvelier didn't care much for a solid documentation of the depicted time period. His visual memory allowed him to render believable surroundings for his characters, but his focus lay on the aesthetics and subtle expressions of humans and animals. Cuvelier had a keen sense of anatomy and perspective, and managed to give his characters an elegant and almost sensual flair. Unfortunately, Cuvelier's specialty proved to be also his weakness. The artist had the tendency to choose the most elegant compositions, even when the story requested a more dynamic approach. Cuvelier seemed in a constant struggle between his fine arts ambitions and regular daytime job. All throughout his career, he was plagued by self-doubt and fear of failure. On top of that, his unhappiness with the work of some of his scriptwriters only furthered his love-hate relationship with the comics medium.

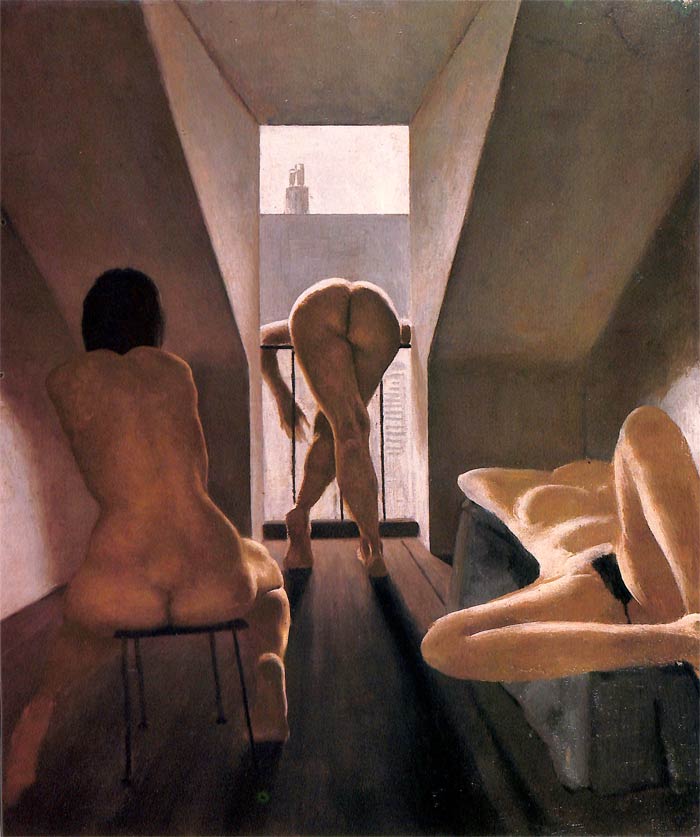

Eroticism

Throughout his career, Cuvelier mostly saw comics as a necessity to earn money. His true heart lay with painting and sculpting, especially nudes, which showcased his passion for the beauty and anatomy of the human body. Cuvelier's fine art was characterized by a form of sensuality that was described as "slumbering eroticism". The same can be said about some of his comics. Most of the time, even the juvenile heroes in his 'Corentin' stories are scantily dressed. The friendship between Corentin and Kim can be interpreted in the same homo-erotic subtext as the companionship between Jacques Martin's main characters Alix and Enak. Cuvelier's final 'Line' story also featured a more sexy presentation of the heroine. The 1973 'Corentin' story 'Le Royaume des Eaux Noires' featured much nudity and hinted at a sexual relationship between the protagonist and the Arabian girl Zaïla.

'Epoxy'. Dutch-language version.

Epoxy

In 1968, Cuvelier made a full-blown erotic graphic novel, scripted by Jean Van Hamme: 'Epoxy'. The story rode along on the wave of adult-oriented comics that had appeared on the market since the mid-1960s, inspired by the U.S. underground comix movement. Free from the restrictions of working for the children's press, authors now aimed their work at a mature audience. In Europe, magazines like Pilote and Hara-Kiri were at the vanguard of this new movement. Frenchman Jean-Claude Forest's sci-fi heroine 'Barbarella' (1962) was the first character that embodied the sexual revolution of the 1960s. In Belgium, Guy Peellaert created the pop art-inspired 'Les Aventures de Jodelle' (1966) and 'Pravda, La Survireuse' (1967), while in Italy Guido Crepax heralded in the "sexties" with 'Valentina' (1965). Dutch authors Thé Tjong-Khing and Lo Hartog van Banda released their pop art graphic novel with the sexy 'Iris' (1968).

At their first 1966 meeting, Cuvelier told Van Hamme he wanted to create a comic for mature readers, with erotic content. Van Hamme proposed to write the story, marking his debut in the comic industry. To give the eroticism a classier status and to avoid being accused of making pornography, Van Hamme took inspiration from Ancient Greek mythology. Since Cuvelier had graduated in Latin and Greek, these themes were right up his alley. The tale follows a young woman called Epoxy, who sails trip the Mediterranean Sea, when a yacht crosses her path. A mysterious character named Koltar imprisons and rapes her. Suddenly, the yacht is destroyed by an unknown force and Epoxy washes ashore. When she wakes up, she finds herself in an ancient Grecian world, having various erotic encounters with mythological characters like Hercules, Bacchus, Pan and Hermes. To emphasize the "Greekness", all dialogue is printed in Greek font.

Since 'Epoxy' was strictly intended for adults, the comic couldn't be serialized in any of the mainstream Franco-Belgian comic magazines, since they all had a family-friendly reputation. Eventually, Van Hamme found Eric Losfeld, a Belgian publisher living in Paris, willing to release it. Earlier, Losfeld had released similar erotic comics like 'Barbarella' and 'Les Aventures de Jodelle', as well as Philippe Druillet's 'Lone Sloane'. Although Cuvelier later reflected on 'Epoxy' as his favorite comic project of his career, it still took several months before he was able to properly finish it. His mood swings got so bad that Losfeld had to pressure him to reach his deadlines.

In the revolutionary month of May 1968, 'Epoxy' was released directly in book format. At first, the book didn't catch much attention, but in later years it was recognized as a masterpiece. One of the first Belgian comic books strictly intended for mature readers and one of the earliest independently published Belgian comics, it also wrote history as one of the earliest Belgian erotic comic books. Throughout the years, 'Epoxy' was reprinted by publishers Horus (1977), Marcus (1981), Clue Circle (1985), Éditions Lefrancq (1997) and Le Lombard (2003). German and Scandinavian translations of 'Epoxy' were however published without the knowledge and consent of the authors, who consequently never received royalties from these editions.

Recognition

In 1974, Cuvelier was awarded the Prix Saint-Michel for his high quality realistic artwork. Since 1989, he is one of the few Belgian comic pioneers to be part of the permanent exhibition at the Belgian Comic Strip Center in Brussels.

Final years and death

Paul Cuvelier spent the final years of his life in poverty, and in a constant search for artistic fulfillment. A final attempt to pick up 'Corentin' was made in collaboration with Jacques Martin, who wrote the script for 'Corentin et l'Ogre Rouge' ("Corentin and the Red Ogre", 1973). Cuvelier abandoned the project after the first pages, which were published posthumously in the 1984 monograph 'Paul Cuvelier: Corentin et les Chemins du Merveilleux' by Philippe Goddin. Martin later used the plot for his 'Alix' story 'Les Proies du Volcan' (1978). Cuvelier was also Jacques Martin's first choice as the artist for his planned comic series about the French serial killer Gilles de Rais. However, Cuvelier was not interested in the project, which was eventually transformed by Jacques Martin and another artist, Jean Pleyers, into the new comic series 'Xan' (1978).

During the final years of his life, Cuvelier served as a mentor for the young artist Pleyers. In a 1993 interview in L'Est Républicain, Pleyers recalled squatting with Paul Cuvelier during most of the 1970s, living in "old embassies, surrounded by homosexual drug addicts". Another pupil of Cuvelier was the Spanish artist Juan Lopez de Uralde, who helped him with the last pages of 'Corentin et le Prince des Sables' in the late 1960s. Paul Cuvelier's final work included some erotic illustrations for Privé magazine in 1975, as well as the preparations of an exposition with the theme "Fillettes" ("little girls"). Before the show saw the light, however, the artist passed away in 1978 in Charleroi after years of declining health. He was 54 years old.

Legacy and influence

Despite his constant doubts and dissatisfaction, Paul Cuvelier remains an influence on several artists to this day. During the early stages of their careers, he was a mentor to Tibet and Jean Graton, regarding drawing animal characters. Jean Pleyers has always kept his mentor in high esteem, while artists such as François Craenhals, Philippe Delaby, Vincent Hénin, René Follet, Anco Dijkman and Tome also mentioned him as an influence. French comic book artist Michel Rouge even named his son after Cuvelier's signature character, and in turn Corentin Rouge has become a comic artist in his own right. The Flemish artists Karel Verschuere and Frank Sels took their inspiration to the limit and copied several of Cuvelier's western-oriented panels for their own comic book productions. Another less flattering form of inspiration appeared in Zorro-Jeudi Magazine of the French publisher Chapelle. Starting in 1947, Cuvelier's 'Corentin' stories appeared in this comic book under the title 'Robin l'Intrépide', but then traced by Jean Pape. Later on, André Oulié reworked the character into a Tarzan-like jungle hero (who kept the name Robin Feldoë), continuing his adventures until 1954. Other artists who have drawn this imitation have been Maurice Toussaint, Pierre Chivot and Maxime Roubinet.

Books about Paul Cuvelier

Historian Philippe Goddin compiled two extensive and highly recommended books about Paul Cuvelier: 'L'Aventure Artistique' (Magic Strip, 1981) and 'Corentin et les Chemins du Merveilleux' (Lombard, 1984).

Paul Cuvelier in his Brussels atelier in 1964 (Photo © F. Bannett).