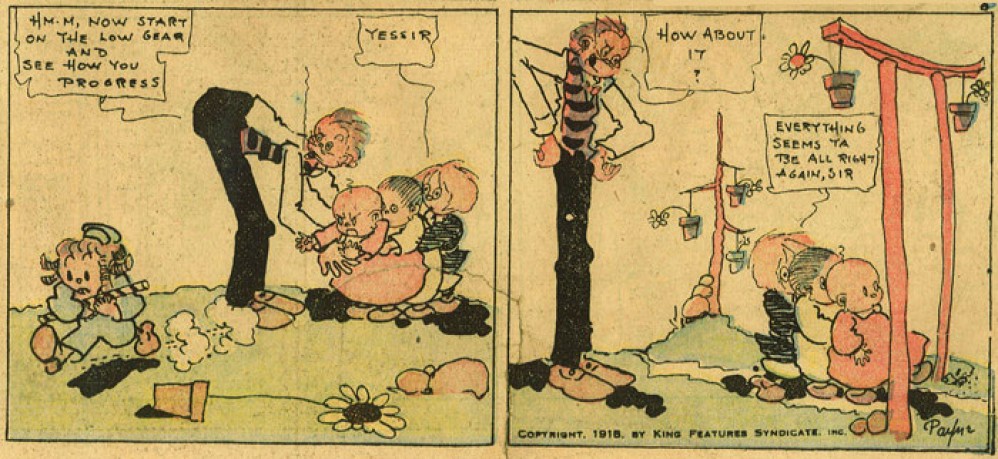

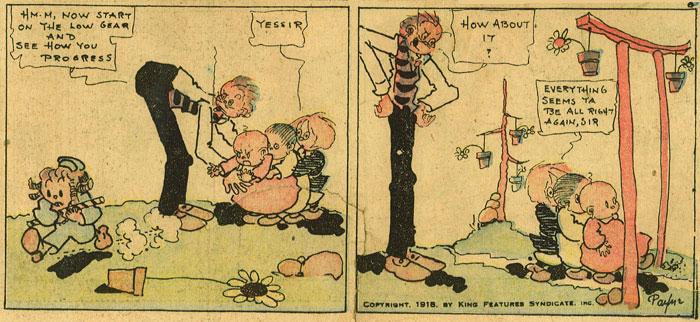

'Say, Pop!' (1918).

C.M. Payne, who sometimes signed as "Popsy", was an early 20th-century American newspaper comic artist, best remembered for his gentle family gag comic 'S'Matter, Pop?' (1910-1940) and its equivalent 'Say, Pop!' (1918-1921). His second longest-running gag comic was 'Honeybunch's Hubby' (1909-1911, 1931-1934) about a henpecked husband. Payne also drew 'Coon Hollow Folks' (1903-1908) and 'Bear Creek Folks' (1904-1912), about anthropomorphic animals in the U.S. South. He was additionally the original artist behind 'Scary William' (1905-1918). Payne was a productive artist who worked in a sketchy, increasingly minimalistic style without backgrounds as his series carried on.

Early life

Charles M. Payne was born in 1873 in the United States in. According to a newspaper article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette of 10 June 1953, he was originally from East Brady, Pennsylvania. He eventually moved to Pittsburgh, where he began sending in cartoon ideas to the local paper. After learning how to draw, Payne became a cartoonist for The Pittsburgh Post in 1896. He then moved to the Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph in 1898 and then to the Pittsburgh Gazette-Times in 1900. As a running gag, he used a little racoon character in all of his newspaper cartoons. Some of his work was signed with the pseudonym 'Coon', in reference to this animal.

'Coon Hollow Folks', 6 March 1910.

Coon Hollow Folks / Bear Creek Folks

Payne's first notable comic was 'Coon Hollow Folks' (1903-1908), which ran as a Sunday page of the Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, signed under the pseudonym "Coon". Set in the U.S. South, starring anthropomorphic animals, 'Coon Hollow Folks' was strongly inspired by Joel Chandler Harris' short stories about 'Uncle Remus and Br'er Rabbit'. In Payne's comic, the Punxsutawney groundhog had a prominent role in the feature, as the cartoonist was an early member of the Punxsutawney Groundhog Club. On 9 October 1904, Payne launched a virtually similar comic strip, 'Bear Creek Folks', which ran in The Philadelphia Inquirer until 8 December 1912. For years it was believed that 'Bear Creek Folks' was merely a retitled version of 'Coon Hollow Folks', but Allan Holtz of Stripper's Guide discovered that they were two separate comic series in two different papers. Both the style, stories and even the characters and their names were exactly the same. Many episodes are, however, unsigned. Holtz guessed that these were probably staff artists who worked for The Philadelphia Inquirer, bringing in people like R. Edward Shellcope, William F. Marriner, Sidney Smith and Jack Gallagher as possible ghost artists. Some were signed with the letter K., like Harold Knerr often did.

'Scary William' (St. Louis Globe Democrat, 21 January 1906).

Scary William

On 26 November 1905, Payne created 'Scary William' for The Philadelphia Inquirer. Contrary what the title seems to imply, the comic isn't about someone who is scary, but a little boy, William, who is disproportionally scared of everything. The tiniest sound, image, light, person, animal or object makes him dash away for safety. Payne continued the series until 10 June 1906, after which Harold Knerr continued it until 25 October 1914. Knerr was assisted by Joe Doyle from 16 August 1914 on, until Doyle continued the series on his own until 2 June 1918.

Honeybunch's Hubby

On 27 November 1909, Payne created 'Mr. Mush' (later retitled 'Honeybunch's Hubby'), which ran until 30 March 1911. It stars a man, Mr. Mush, and his dominant wife, which he names "Honeybunch". The series ran in the Evening World for two years and was revived 20 years later, on 19 April 1931. Oddly enough, Payne already had a successful and long-running comic strip in his hands, 'S'Matter, Pop?' (see below), but he still demoted it to a topper comic on top of his Sunday page, while 'Honeybunch's Hubby' now became the main feature. After 8 months, he changed his mind and made 'S'Matter, Pop?' the main comic again, while 'Honeybunch's Hubby' continued as a topper until 22 July 1934. Allan Holtz of Stripper's Guide has nevertheless noticed some advertising from 1937 still promoting the comic, leaving the possibility that the series might have run until that date instead.

'Honeybunch's Hubby' (Des Moines Tribune, 18 August 1910).

S'Matter, Pop?

In 1910, Payne created his signature daily comic 'S'Matter, Pop?' (1910-1940), which ran in the New York World, owned by Joseph Pulitzer, and the New York American, owned by William Randolph Hearst. The Sunday comic started a year later under the title 'Those Kids Next Door', which became 'Nippy's Pop' in 1914 before eventually continuing as 'S'Matter, Pop?' as well from 1918 on. The series stars a dim-witted father, his dominant wife, their naïve son, Willyum, and a little baby. The dad never received a proper name. Instead everybody named him "pop". Pop is often victim of circumstances beyond his capacity to understand or prevent them. His son is naughty, but in a charmingly innocent way. Whenever Pop gets hurt or humiliated, the boy delivers the comic strip's punchline (and title): "What's the matter, pop?", while the reader well understands why the poor father is upset. A more mean-spirited child character in the comic is Desper't Ambrose ('Desperate Ambrose'), who lives in the neighborhood. Ambrose always speaks in an odd, melodramatic tone and announces himself as if he is a theatrical character: "Tis I, Desper't Ambrose". Many of his pranks border to the sadistic, while never showing any remorse.

By 1917, 'S'Matter, Pop?' was continued by the Bell Syndicate, for which Payne wrote and drew his feature until 21 September 1940. During this time, it mostly ran as a Sunday strip in the New York World, followed as a decades-long-running daily strip in The Sun.

Say, Pop!

Like 'Coon Hollow Folks' and 'Bear Creek Folks', Payne at one point created a completely similar but separate strip called 'Say, Pop!' for the King Features Syndicate, between 2 January 1918 and 1921. And just like these two comics, 'S'Matter, Pop?' and 'Say, Pop!' have often been confused by comic historians for being one and the same series. Even readers sometimes couldn't tell them apart. For instance, Charles M. Schulz once cited 'Say, Pop!' as an influence on 'Peanuts', though given that 'Say, Pop!' had already ended one year before his birth, it's more likely that he meant 'S'Matter, Pop?', which still ran in papers during his childhood.

Little Johnny Bear

As early as 12 September 1926, 'S'Matter, Pop?' received a topper comic, though in this early stage it was merely an additional gag with the protagonists from 'S'Matter Pop?'. On 23 January 1927, it changed its set-up to 'Little Johnny Bear', being a spin-off of 'Bear Creek Folks' focusing on the bear cub Johnny. It took until late 1930 before a title sprung up and until March 1931 before it was permanently titled 'Little Johnny Bear'. Only a month later, though, on 12 April 1931, Payne replaced 'Little Johnny Bear' with 'S'Matter, Pop?' itself as a topper, giving 'Honeybunch's Hubby' the honor of being the main comic.

'S'Matter, Pop?' (The Evening World, 28 July 1911)

The Little Possum Gang / Little Kid Trubbel

Other Payne creations for the Philadelphia Inquirer were the Sunday comics 'The Little Possum Gang' (4 April 1909) and 'Little Kid Trubbel' (7 August 1910). 'The Little Possum Gang' was a children's gang comic, with the gimmick that the characters were anthropomorphized opossums. 'Little Kid Trubbel' starred a little boy who (usually unintentionally) causes wacky antics and mayhem to his environment. In December 1912, Payne passed the pencil for both comics to Jack Gallagher, who continued them until October 1918.

Peter Pumpkin

Also for The Philadelphia Inquirer, Payne created the gag comic 'Peter Pumpkin' on 16 July 1911. The title character is a corpulent, bald boy with only one hair on his head. He has a reputation for knowing all the answers to kid's questions, but in every episode it turns out that the other kids are far more knowledgeable about the subject than him. By 5 November of that same year, Payne grew tired of the format and quit the series.

Chantecleer - He's A Bird / Little Sammy

For the New York World and its Press Publishing syndicate, Payne additionally created 'Chantecleer - He's A Bird' (3 March - 1 September 1910), about a rooster, and 'Little Sammy' (1914-1915) in the New York World. The latter comic should not be confused with Winsor McCay's 'Little Sammy Sneeze' .

Final years, death and legacy

Payne was a productive cartoonist, creating several comics for many different newspapers. He tended to continue them as long as possible, using a pragmatic method to reach his deadlines. The artwork is often sketchy, with backgrounds being reduced to nothing but a white void. Payne simply used what he needed for the gag: his regular cast, some props and occasional side characters. In the early 20th century, most U.S. newspaper comics featured elaborate, very detailed artwork, spread out over entire pages. Payne's comics therefore stood out, being easy to read quickly, but on the downside equally easy to quickly forget.

Payne's reasons to keep his comics running as long as possible were presumably financial. His comics career appears to have ended by 1940 and despite his earlier success, he slowly but surely succombed to poverty. In June 1953, when he was eighty years old, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that Payne was making his own puppets and planned his own TV puppet show. It is unknown if these plans ever came to fruition. In the 1950s many U.S. newspapers made their comics pages much smaller, forcing cartoonists to focus on more minimalistic artwork and verbal comedy. If Payne still had been active in the comics industry at this point, he might've been more in his element.

Instead, Payne lived in Harlem, New York City, in a cheap apartment. A colleague, Vernon Greene, often visited him in his apartment, bringing him food and money. He also helped him get a refrigerator with a lock and chain, so he wouldn't have to go out every day for groceries and other residents wouldn't steal from it. Hy Eisman, who was Greene's ghost artist in the mid-1960s, recalled that he was never allowed to see Payne and told to wait in the car whenever Greene brought the impoverished Payne his supplies. One time, Payne agreed to meet Eisman and even dressed up for it. Eisman: "Apparently, without a reason, Payne suddenly changed his mind. As Vern shut the door, I could only see the image of a slight man in a full tuxedo, with top hat."

According to a letter he sent to fan Rick Marschall (reproduced on John Adcock's blog on 1 December 2018), Payne was victim of a robbery in 1963. This also explains why Greene took care of him. Nevertheless, he couldn't be there for him always. One day in 1964, Greene was shocked to hear that Payne went missing. He called hospitals in Harlem and was informed that Payne was dead. He had been found in the street, but it was never confirmed whether he died there, or later in the hospital. He was 90 or 91 years old. The city paid for his cremation and was about to bury him in Potter's Field, but Greene retrieved the ashes and offered to send them to Payne's family. However, his family refused to accept this gift, never explaining their reasons. Greene therefore kept Payne's ashes in his own file cabinet and once showed them to Eisman joking that he "finally got to meet him, after all." Greene himself would die a year later, in 1965.

The Pittsburgh Post Gazette about 80 year-old Payne's plans for his TV puppet show (10 June 1953).