Edward Gorey was a mid- to late 20th-century American writer and book illustrator. Often pigeonholed as a "children's author", his surreal, ominous but often witty stories also gained him a cult following among adults. Gorey's books are a peculiar mixture between illustrated poetry, dark nonsense and dry, black comedy. His signature work is 'The Gashlycrumb Tinies' (1963). He remains a highly popular and influential author, whose style is still imitated to this day, leading to its own eponym: "Gorey-esque".

Early life

Edward Gorey was born in 1925 in Chicago, Illinois, as the son of a journalist. At age 11, his parents divorced. Gorey's stepmother was cabaret singer Corinna Mura, best-known among film fans as the guitarist in 'Casablanca' (1942), raising the spirits of the café visitors by singing 'La Marseillaise'. Later, Gorey's biological parents remarried, but by then he was already 27. Gorey was a gifted child: at age three, he already taught himself to read. His favorite novelists were Jane Austen, Lewis Carroll, Agatha Christie, Louis Feuillade, Ronald Firbank, Robert Musil and Anthony Trollope. He also enjoyed Chinese and Japanese literature. Initially, he also read Charles Dickens, but when interviewed by Newsday (8 November 1998), he revealed: "Unfortunately, there was an anecdote I read about Dickens, and I haven't read a word of Dickens since. I haven't told anybody, I don’t wish to burden anybody with it. It haunts me." Gorey took the mystery of what he read about Dickens and where he found this information to his grave.

Thanks to his evolved reading skills, Gorey was able to skip the first and fifth grade. In high school, one of his classmates was the future Hollywood actor Charlton Heston. Gorey studied French at Harvard University, where his roommate was another future celebrity, poet Frank O'Hara. After graduating with a BA in French in 1950, Gorey and some of his fellow graduates co-founded the Poets' Theatre in Cambridge. He made a living as an office clerk in several book stores.

In 1943, Gorey spent one semester at the School of Art Institute of Chicago, but left, making him basically a self-taught artist. He credited his graphic talent to his maternal great-grandmother, Helen St. John Garvey, who was a greeting card illustrator in the Victorian era. Among his graphic influences were the painters Francis Bacon, Balthus, Giorgio di Chirico, Max Ernst, Giorgione, Frans Hals, Winslow Homer, Michelangelo, René Magritte, Pablo Picasso, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Rembrandt van Rijn and Johannes Vermeer. In the field of illustration, he admired Edward Lear, John Tenniel and James Thurber.

Later in life, Gorey religiously watched live-action TV shows like 'Doctor Who', 'Buffy the Vampire Slayer' and 'The X-Files' and was also fond of the animated shows 'Batman: The Animated Series' (1992-1995) - based on the DC comic created by Bob Kane - and 'Ned's Newt' (1997-1999). In terms of comics, he loved George Herriman, Lyonel Feininger, DC Comics, Marvel Comics and - surprisingly enough - the works of the French creators René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo. His personal library not only lists several 'Astérix' albums, but also rare English translations of Goscinny and Uderzo's other series, 'Oumpah-Pah'. When Gorey was interviewed for Proust's famous Questionnaire in 1997, he named 'Astérix' one of his favorite names.

'The Gashlycrumb Tinies' (1963).

Literary career

Between 1953 and 1960, Gorey made his earliest book illustrations for the Art Department of Doubleday Anchor in Manhattan, New York City. His art adorned the covers of novels like Bram Stoker's 'Dracula', H.G. Wells' 'The War of the Worlds' and T.S. Eliot's 'Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats'. He was mostly associated with the works of children's book author John Bellairs and his successor Brad Strickland. In 1962, he established the Fantod Press to publish books that couldn't find a publisher elsewhere. By 1964, he was a full-time writer and illustrator.

His earliest self-written and self-illustrated book was 'The Unstrung Harp' (1953), which visualized in 30 images how a writer works on a book. Yet every image is full of odd details that are never explained in the equally strange narration. Stylistically, the book is comparable to the Dadaist graphic novels of Max Ernst, of whom Gorey was an admirer. A celebrity fan of 'The Unstrung Harp' was novelist Graham Greene (best known for 'The Third Man') who named it "the best novel ever written about a novelist, and I should know!". Gorey wrote and illustrated several strange books throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, but only found true literary fame by the end of the 1970s, once the first generation of children's book readers had grown up. He kept releasing new titles until 1999.

Summarizing Gorey's full bibliography is complicated, since he illustrated over 300 books, several of which under pseudonyms. He enjoyed using vowels and consonants of his own name and rearranging them into anagrams. One notable title was the first edition of 'Alvin Steadfast on Vernacular Island' (The Dial Press, 1965), written by Mad scriptwriter Frank Jacobs. Some of Gorey's books are presented in the style of an alphabet, explaining a variety of situations by going through all 26 letters. In 'The Fatal Lozenge' (1960), he focused on occupations, and in 'The Gashlycrumb Tinies' (1963), he visualized the causes of death of 26 children. Others were written in the style of limericks ('The Listing Attic', 1954) or told in pantomime ('The West Wing', 1963).

Style

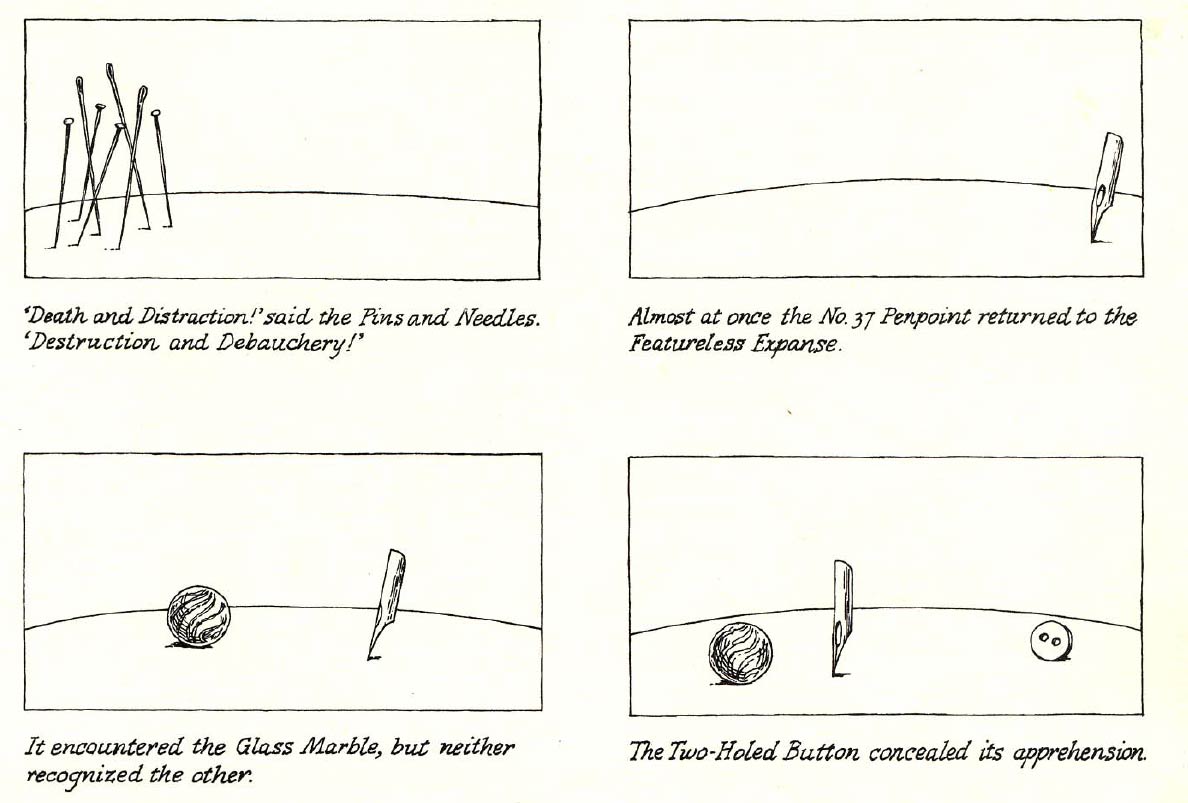

Despite being active in the second half of the 20th century, Gorey's books have an old-fashioned, Gothic look, echoing the great children's classics from the Victorian and Edwardian Age. In terms of content, though, they are closer to the nonsensical style of Edward Lear ('The Owl and the Pussycat') and Lewis Carroll ('Alice in Wonderland'), with the "scare 'em straight" undertones of ancient fairy tales and children's books like Heinrich Hoffmann's 'Der Struwwelpeter'. In 'The Doubtful Guest' (1957), for instance, a penguin visits a family and stays at their home, despite stealing and breaking some of their property. The book has a sinister atmosphere, especially when it is revealed that this strange bird has been living in the family's home for 17 years. Readers never find out why the bird is there or why the family couldn't get rid of it. In 'The Bug Book' (1959), a group of bugs are bugged by a bigger bug and crush him with the help of a big rock. In 'The Gashlycrumb Tinies' (1963), Gorey visualizes the deaths of 26 little boys and girls in alphabetical order and in rhyme. Topping it off is the final illustration, depicting all their tiny gravestones together. In 'The Stupid Joke' (1990), a young boy stays in bed all day, pretending to be dead, with dire consequences afterwards. It comes to no surprise that many readers consider Gorey's name an excellent description of his macabre style. Despite what some may assume, it wasn't a pseudonym, but his real name.

Gorey's books are difficult to pigeonhole. The stories follow the structure of a children's book, yet some adults consider them too strange and disturbing for this target audience. 'The Epiplectic Bicycle' (1969), for instance, uses the word "epiplectic" that even most adults would need to look up in a dictionary to understand. The story centers on an anthropomorphic bicycle, which wouldn't be out of place in a traditional children's book, but here the bike is so sentient that it can actually feel pain and drive a group of kids wherever it wants. Some of Gorey' stories read like cautionary tales, though lack a clear moral. Others are just a progression of baffling events that leave the reader scratching their heads afterwards. In 'The Hapless Child' (1961), for example, we follow a young girl who becomes the subject of a series of increasingly bleak and horrible events. The book ends with her father barely recognizing her afterwards and no genuine happy end.

Gorey himself classified his work as "nonsense literature". The surreal horror is often juxtaposed with black comedy, described in such dry narration that some audiences find it hilarious, rather than frightening. In the previously mentioned 'Bug Book', for instance, the bugs put the flattened corpse of the bullying bug inside an envelope and address it to "whom it may concern". Afterwards they have a party "and everyone enjoyed himself immensly." Some of the children's deaths in 'The Gashlycrumb Tinies' are plausible, others quite far-fetched, like "being assaulted by bears", to downright silly, like little Neville who "dies of boredom." In 'The Hapless Child', the father of little Charlotte Sophia looks for his long lost daughter. Just when they seem to have a happy reunion, he accidentally runs her over with his buggy! Although Gorey is associated with macabre, sometimes bizarre children's stories, some of his books are more straightforward and family friendly, like 'The Wuggly Ump' (1963), in which a group of children discover a strange creature named The Wuggly Ump. Overall, Gorey was an eccentric creative soul, who enjoyed putting his personal pet peeves in all his stories, namely ballet, fur coats, tennis shoes and cats.

Even when Gorey actually made a picture book for mature audiences, 'The Curious Sofa, A Pornographic Work' (1961), it wasn't quite what the marketing promised. 'The Curious Sofa' is perhaps one of the strangest pieces of erotica ever conceived. Gorey intended the book as a spoof of Pauline Réage's erotic novel 'Histoire d'O', but never depicts any actual sex, or nudity for that matter. All innuendo is suggested in the narration and the images, purely based on readers' overactive imagined expectations. The tale even has a dark, yet equally vague ending, making the eroticism even more dubious. What makes the book especially intriguing is Gorey's own mysterious sexuality. Interviewed by Lisa Solod in Boston Magazine (September 1980), Gorey said: "I suppose I'm gay. But I don't really identify with it much. I am fortunate in that I am apparently reasonably undersexed or something. (...) What I'm trying to say is that I am a person before I am anything else." Since Gorey was a lifelong bachelor, with no apparent partners recorded by history, some have described him as asexual. Others have stated that Gorey was homosexual, but grew up in an era when this was socially highly unacceptable and perhaps never felt comfortable coming out, even when the sexual revolution of the 1960s made LGBT issues less of a taboo. Either way, it could explain why 'The Curious Sofa' is so devoid of genuine eroticism.

Gorey has also been accused of being a child hater. In several of his books infants either die gruesome deaths or, like in 'Beastly Baby' (1962), are depicted as a cruel, unlikeable monstrous being. In reality, he never expressed any negative feelings towards children. People who knew him personally described him as somebody who didn't mind the presence of children, and vice versa. He was also fond of animals, owning various cats and letting a bunch of raccoons nestle in his attic.

Other media

In addition to books, Edward Gorey also worked in other media. He designed costumes for a Broadway adaptation of 'Dracula' (1977) and the opening credits for the horror anthology TV series 'Mystery!' (1980-2006) on PBS, animated by Eugene Federenko, Derek Lamb and Janet Perlman. In 1985, he wrote the first of 10 musical revues, titled 'Tinned Lettuce'. From 1987 on, he wrote and directed various plays, librettos and puppet performances for the Theatricule Stoique.

Recognition

Gorey's anthology book 'Amphigorey' (1972) won an American Institute of Graphic Arts Award. His costume designs for 'Dracula' (1977) received a Tony Award. His trophy case featured the New York Times Prize for Best Illustrated Novel (1969) (1971), the Deutscher Jugendliteraturpreis (1977), the Edgar Allan Poe - Raven Award (1978), two World Fantasy Awards (1985, 1989) and in 1999, the Bram Stoker Award for his entire career. Already in his lifetime, Gorey's artwork was the subject of various exhibitions, which continued after his death.

Final years and death

From the 1960s until the early 1980s, Edward Gorey lived in New York City, where he attended each new New York City Ballet performance choreographed by George Balanchine. After Balanchine's death in 1983, Gorey no longer saw the need to stay in "the city that never sleeps" and settled in Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod. In 2000, he passed away from a heart attack, at age 75. Gorey left all his money to animal charities.

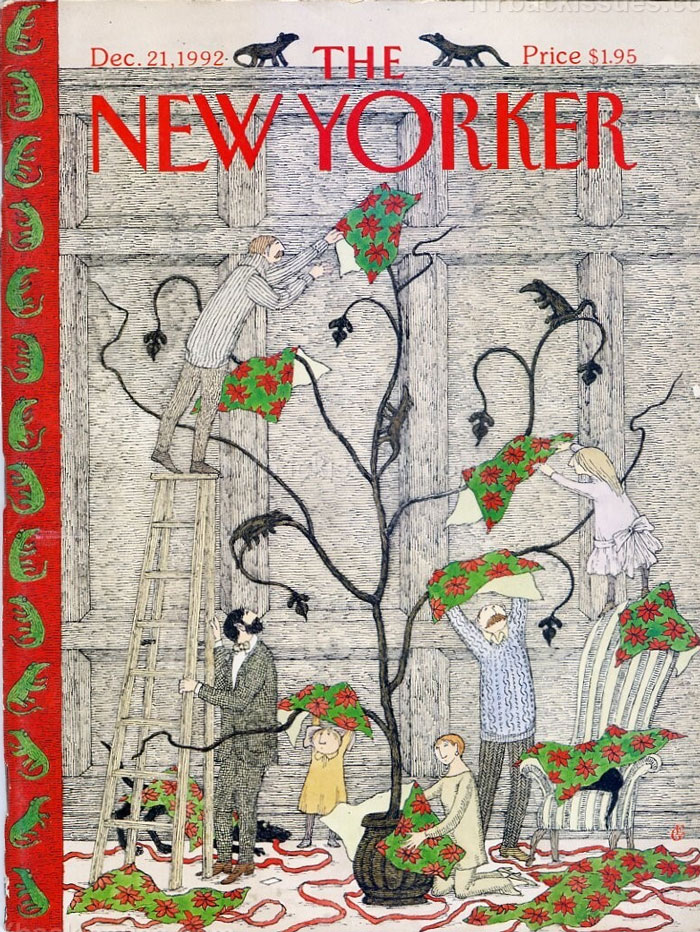

Edward Gorey on the cover of The New Yorker in 1992 and (posthumously) in 2018.

Legacy and influence

Edward Gorey's cult fame already rose during the final years of his life, only to skyrocket after his death. His books are still subject of critical analysis and many different interpretations. Some have been adapted into musical pieces, like 'The Hapless Child' (1976) by Michael Mantler, 'The Evil Garden' (2001) by Max Nagl, 'The Gorey End' (2003) by The Tiger Lilies and The Kronos Quartet, 'The Doubtful Guest' (2006-2007) by Stephan Winkler and 'A Gorey Demise' (2007) by Creature Feature. Mark Romanek's music video 'The Perfect Drug' by Nine Inch Nails was directly inspired by Gorey's work. Notable celebrity fans of Gorey are painter Oskar Kokoschka, film director Tim Burton and novelists Daniel Handler (of 'Lemony Snicket's Series of Unfortunate Events' fame), Alison Lurie (of 'Foreign Affairs' fame) and John Updike (of 'Rabbit Run' fame).

His style is so recognizable that it inspired an eponym, "Gorey-esque". Since 2015, an online journal is syndicated devoted to Gorey's work and authors and artists who are similar to his style, aptly titled Goreyesque. One artist whose work is often compared and confused with Gorey is Domenico Gnoli, particularly his illustration 'What Is a Monster? Snail on a Chair' (1967), depicting a fish in a snail's house lying on a sofa. In the United States, Edward Gorey was an influence on Alison Bechdel, Gary Larson, Rob Reger, Richard Sala, Maurice Sendak and Terry Gilliam. Gilliam was one of several people who were interviewed in Christopher Seufert's documentary, 'The Last Days of Edward Gorey' (2015). The author also inspired the webcomic 'Edward Gorey's 'The Trouble with Smithson' by Shaenon Garrity, Robert Stevenson, Brian Moore and Roger Langridge. At the end of 'The Simpsons' episode 'The D'oh-cial Network' (2012) by Matt Groening, a short atmospheric film can be seen, 'Story's Too Short', paying homage to Gorey's trademark style. In the December 2018 issue of Mad Magazine, Matt Cohen and Marc Palm created 'The Ghastlygun Tinies', a parody of Gorey's 'Gashlycrumb Tinies', satirizing school shootings. Their spoof received considerable media coverage, with some people finding the subject matter in very bad taste, while others felt it mimicked Gorey perfectly and was a stinging satire of one of the United States' most recurring problems. Monte Beauchamp included Edward Gorey in his book 'Masterful Marks: Cartoonists Who Changed The World' (Simon & Schuster, 2014), where the cartoonist's life story was adapted in comic strip form by Greg Clarke.

Outside the USA, Gorey also found admirers in Canada (Dave Cooper), while in Europe he has disciples in Belgium (Jean-Louis Lejeune), France (Jean-Emmanuel Vermot Desroches ) and the United Kingdom (Neil Gaiman, particularly for 'Coraline').

Most of Edward Gorey's work has been collected in the books 'Amphigorey' (1972), 'Amphigorey Too' (1975), 'Amphigorey Also' (1983) and 'Amphigorey Again' (2006). Since 2002, his house, located at 8 Strawberry Lane, Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts, is now a museum devoted to his work.

Goreyography site: the works of Edward Gorey

goreyana.blogspot.com