Ding Cong (丁聪), who often signed with 小丁 ("Xiao Ding") was a notable Chinese cartoonist, caricaturist, painter, illustrator and designer of magazine covers. He was celebrated for his satirical cartoons, which mocked modern Chinese society. Unfortunately, under Mao's regime, Ding Cong was sent to hard labor camps twice for his "subversive activities".

Early life

Ding Cong was born in 1916 in Shanghai, as the son of the famous caricaturist Ding Song. Despite having a cartoonist for a father, Ding Cong was strongly discouraged from following a similar career path. His father wanted him to find a more lucrative career. Still, Ding Cong pursued his dream and borrowed all of the comic and drawing instruction books his parents couldn't afford from friends. He studied at the Shanghai Fine Arts Institute and was particularly inspired by American magazines like Vanity Fair and The New Yorker. His main graphic influences were Zhang Guangyu, Ye Gianyu and Miguel Covarrubias. Ding Cong signed some of his work with the pseudonym "Xiao Ding", meaning "Little Ding".

Career

In 1930, at age 17, Ding Cong sold his earliest cartoons and caricatures to a magazine called "Good Friends" and to the satirical magazine Qing Ming. He additionally worked as a graphic designer, promoting films, and edited the illustrated magazine Liangyou. He broke through during the 1930s and 1940s, as one of the house cartoonists of the literary magazine Dushu, which he remained for more than 30 years. Between 1937 and 1945, he was an art teacher, stage designer and editor. In 1939, Song Qingling, the widow of Chinese former president Sun Yat-Sen, selected Ding Cong's drawing 'Refugees' to motivate people into donating money to support Chinese refugees.

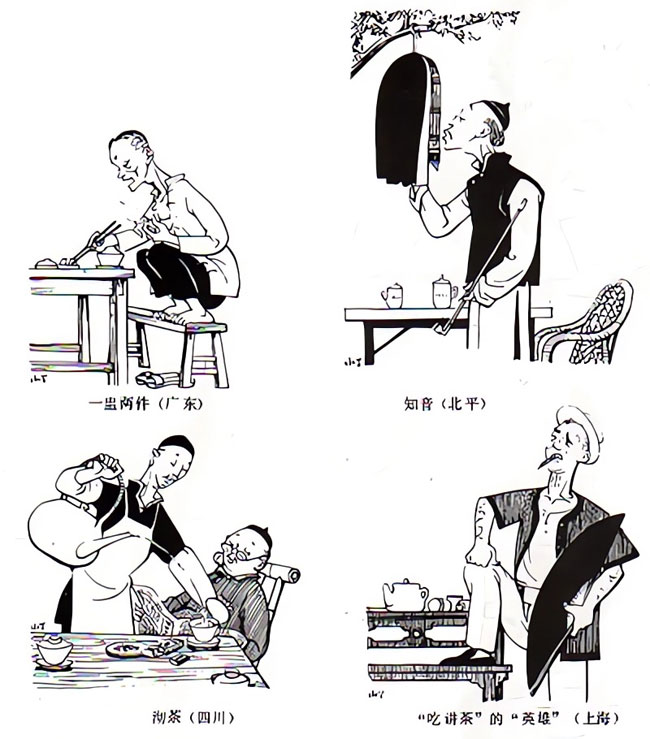

'In Remembrance of the Teahouses'.

During this period, World War II broke out and Japan invaded China. After the Japanese army bombed Shanghai in 1940, Ding Cong fled to Chongqing. Since it was a dangerous time to make political cartoons, he was more preoccupied with illustrating novels and painting. Together with other artist friends, he travelled to Myanmar (present-day Burma), Vietnam and Hong Kong. He made marvelous woodcut illustrations for famous novels by writers Lu Xun, Mao Dun and Lao She (not to be confused with the philosopher Lao-Tse or Laozi). One of his best-known paintings, 'Images of Today (also translated as 'Present Day'), was made in 1943. The work depicts corruption and moral decay during wartime, but with a little comedy added in the mix.

Post-World War II

After World War II, Ding Cong first returned to Shanghai, and then worked in Hong Kong between 1947 and 1948. He had a column in the magazine Dushu ("Reading") and was founder-editor of the People's Pictorial (1956). In addition to his one-panel cartoons and celebrity caricatures, he made a comic series titled 'Reflections on Society', a satirical look on present-day China, complete with criticism of the ruling nationalist party of president Chiang Kai-Shek. On 31 December 1956, Ding Cong married Shen Chong (1928-2014), a woman who had unwillingly become nationally famous in 1946, after being raped by two U.S. marines, which was a national scandal at the time.

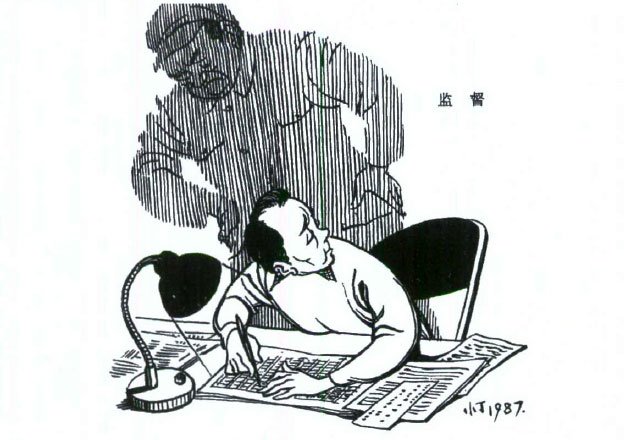

'Inspection and Supervision' (1987).

Imprisonments

However, Ding Cong's biting cartoons weren't always tolerated by the Chinese government. His cartoon 'Reality' linked extreme poverty to the nationalist authorities under Chiang Kai-Shek. It brought Ding Cong into trouble and the cartoonist was forced to go into self-imposed exile in Hong Kong. In 1949, China became a Communist Republic. Now it was Chiang Kai-Shek's turn to seek other horizons, while Mao became the new head of state. But for Ding Cong things didn't improve. During the Great Leap Forward (1956), the country had to be modernized and purified. One of Ding Cong's essays, 'Wan Xiang' ('10,000 Phenomena', 1956), made a plea for a magazine under creative control of editors, rather than government officials. He was instantly arrested for promoting subversive ideas. Since he had been active in an artistic commune known as the "House of Loafers", he made himself even more suspicious. Especially since two members of this commune, playwright Wu Zuguang and cartoonist Huang Miaozi, had also been arrested for similar charges. Ding Cong was sentenced to three years' hard labor in the province Heilongjiang. After liberation, he was banned from drawing cartoons any longer.

In 1966, Mao announced another policy, the Cultural Revolution. From now on, all artists would be scrutinized whether they "supported bourgeoisie tendencies and counter-revolutionary activities." Ding Cong was one of many people who ended up in a labor camp, separated from his wife and son for several years. Another Chinese cartoonist who suffered the same fate was Rao Pingru. Even while being "re-educated", Ding Cong kept his spirits up. When his guards weren't looking, he sketched his fellow inmates. Even when they took his paper and pencil away, Ding Cong used pieces of plastic and wood.

In 1976, Mao died and the new regime reversed many of his previous, controversial political decisions. Several people were rehabilitated, including Ding Cong, who was freed in 1979.

A bust of 'Docile Man' (1945).

Final years and death

In 1979, Ding Cong settled in Beijing, where he enjoyed a long life in relative freedom. He even picked up the pencil again after 20 years. The senior artist became an outspoken opponent of the censorship laws and a critic of the corruption within the Chinese communist system. A typical example of his style is a cartoon in which a government official asks an electrician to install a new doorbell "at ankle height". When the engineer asks him "how guests will ring the bell", the corrupt official replies: "My guests all use their feet to ring the bell, since their hands are full with gifts for me." In another, a man counts his job bonus under a tree. When a passerby asks him why he isn't working to increase his bonus, he answers: "Whether I work or not, I still get the bonus."

Ding Cong was now over 60 and didn't care any longer what people thought of his work. He simply wanted to express what he was forbidden to say for more than 20 years. And he had a lot of cartoons to catch up with. Interviewed by journalist Teresa Poole for The Independent (11 November 1996), he explained that he avoided trouble by addressing problems without directly attacking individuals. Otherwise he would have been arrested. In old age, Ding Cong became head of the Cartoon Committee of the Chinese Artists' Association. From 1990 on, he livened up the columns of Chen Siyi with illustrations, serialized in the magazine Reading. They made more than 200 episodes, before Ding Cong's diminishing health forced him to pass the pencil to Huang Yonghou, who continued illustrating the columns for more than 20 years.

On 13 April 2009, Ding Cong was sent to the hospital due to a cerebrovascular disease. He fell into a coma from which he never awakened. Over a month later, on 26 May 2009, he died at age 93. He had asked for a simple funeral, with no farewell ceremony and no spreading of ashes.

Legacy and influence

After Ding Cong's death, the Library of Congress held a symposium celebrating his career. His work has also been translated into English, French and German. For those interested in his life and career, 'Wit and Humour from Ancient China' New World Press, 1997) and Marcia R. Ristaino's 'China's Intrepid Muse: The Cartoons and Arts of Ding Cong' (Floating World Editions, 2009), are highly recommended.